What does it mean to be literate in a digital age? While “literacy” conventionally implies reading and writing, we can also apply the concept to new media. By scrutinizing how we use our digital creations, designers can better understand their ability to effect change.

It’s been called a publishing platform and a conversation medium, but it’s also been used as a collaborative encyclopedia, a code playground and a canvas for art. Is there anything the web can’t do? And should there be?

Analog media (e.g. books, magazines, newspapers) were relatively simple, after all. Everything we needed to know in order to think critically about them came down to reading and writing (or so we believed). But the web is different. Not only does it allow us to create new ideas along existing channels—we can publish and share the digital equivalent of books, magazines, and newspapers, for example—it also allows us to create new channels altogether, such as Twitter. So what does that mean for our conventional definition of literacy?

Media theorist Clay Shirky offers a clue. In his foreword to the the book Mediactive, Shirky provides a media-agnostic definition, suggesting that “literacy, in any medium, means not just knowing how to read that medium, but also how to create in it, and to understand the difference between good and bad uses.” This definition resonates with me—indeed, I might go so far as to say it should resonate with all user-centered designers—for not only do we, as designers, strive to understand the way the web is created and consumed, we also wish to understand what it means to create a “good,” useful web for our users.

The following three-part series, then, serves as an exploration into digital literacy. In this, part 1 of the series, I’ll begin with a story that illustrates some of the web’s more esoteric aspects: the elements that make it similar to, but altogether different from, print. In the second, I’ll briefly discuss the prominent double-diamond model of design thinking and explore how “design posture” might affect our ability to navigate that model. In the third, I’ll point to nascent trends in our profession, ways in which both investigative journalism and teaching pertain to our work.

A design villain

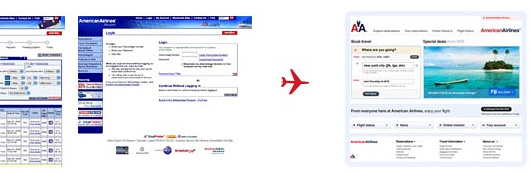

In May of 2009, an interaction designer named Dustin Curtis published an open letter on his personal website entitled “Dear American Airlines.” In it, Curtis suggested that the company take a look at his vision of what their future home page might look like:

The difference was profound. Instead of providing users with a cramped, uninspiring sea of text, the designer placed the booking process—arguably the most important interaction on the page—front-and-center. He even included a photo of an island getaway. Few would argue that Curtis wasn’t onto something, so that’s precisely when he decided to turn up the heat, asking the company to “fire [their] entire design team,” who, he added, “is obviously incapable of building a good experience.” He concluded with a suggestion that American Airlines “get outside help.”

As those watching the saga unfold later learned (in a response from an unnamed designer working at American Airlines, going by the pseudonym “Mr. X”) what prohibited the company from redesigning its website wasn’t a lack of desire or any incompetence on the part of its in-house talent. Rather, it was their corporate culture. As Mr. X explained it, the public probably wouldn’t see the fruits of his group’s labor for at least another year simply due to the degree to which teams at American depended upon one another (i.e. bureaucracy). This meant that the company actually had two problems: not only did it have a poorly designed homepage, it also had a poorly designed organization that made it difficult to effect change.

In many ways the state of affairs at American Airlines probably came as no surprise to Dustin (or anyone else, for that matter). Of course they had a poorly designed organizational structure; why else would their homepage have fallen into such disarray? That’s a fair question and, in fact, it’s probably what led Dustin to publish his open letter. A more prudent question, however (and one that apparently nobody thought to ask), is this: What should American Airlines have done? Clearly they couldn’t just fire their entire design team, as Dustin suggested. How should they have gone from where they were to where they needed to be?

It’s the question that drives us

To better understand how a designer might begin to solve the organizational problems plaguing American Airlines, it’s worth taking a step back and more thoroughly considering the role that Dustin played with regards to American Airlines, vis-à-vis the publication of his open letter. There are many ways in which Dustin could have expressed his opinion, after all: he could have called or written customer support; he could have sent an angry letter (you know, in the mail); he could have written a Yelp review (customers occasionally comment on websites as part of their business reviews). Dustin didn’t do any of these things, however. Instead, he published an open letter, subjecting his inquiry to the web’s seldom-discussed-but-nonetheless-profound political affordances.

A political affordance is simply an amalgamation of concepts originating from the fields of social science (politics) and psychology (affordances). Whereas a perceived affordance allows someone to determine the potential utility of her implements by way of what she perceives (e.g. the shape of a hammer’s head affords hitting, its handle affords holding, etc.), a political affordance describes her (often unperceived) ability to assemble and direct a public—to “call an audience into being”—by way of her media.

To put this into perspective, consider the difference between a telephone conversation and Facebook post in terms of the politics they afford. Unless it’s a conference call, a telephone conversation is generally believed to be held between two people: the caller and the person being called. A Facebook post, on the other hand, can be visible to any number of people: you and your friends, yes, but also, potentially, your parents and your future employers. The internet’s political affordances have a profound impact on the ways in which we create, consume, and disseminate information.

Now, returning to the issue of Dustin’s role vis. his open letter, let’s consider the alternate route. By contradistinction, consider a web designer who places a redesigned version of the American Airlines website in his online portfolio in hopes that the finesse it demonstrates will garner him future employment. This happens all the time. While Dustin and our hypothetical designer have each presented “alternate realities,” the web’s political affordances greatly magnify the ramifications of the ways in which these designers have chosen to express their respective sentiments. Both expressions are online; both are universally available; both assemble a public and affect its sentiment towards American Airlines. In so doing, our hypothetical designer’s message is likely considered “friendly” whereas Dustin’s open letter is almost certainly seen as adversarial.

Distinguishing between these two modes of presentation might seem superfluous—and, indeed, it would be of less consequence—if it weren’t for the fact that questions lie at the heart of what we do as designers: designers ask questions in order to better understand the boundaries between form and function; designers ask questions in order to understand what users want; and designers ask (rhetorical) questions when they present wireframes, prototypes, etc. to their team. (None of these actions is explicitly “at odds” with a system, though. Quite the opposite. Designers generally question things in order to attain a shared understanding.)

In this TED Talk—coincidentally given the same year as Dustin published his open letter—psychologist and author Barry Schwartz “makes a passionate call for ‘practical wisdom’ as an antidote to a society gone mad with bureaucracy.” This is a challenge that creative consultants frequently face.

The difference between consulting in a world before the internet existed and consulting in the age of digital media is that today’s media landscape requires us to more thoroughly consider the media we employ. When designers are retained by a client, they’re typically asked to “criticize” that company in private. Because the company explicitly invited them in, that company is more likely to be open-minded and develop institutional wisdom. When designers aren’t retained though—or when criticism happens in public, as was the case with Dustin— designers run the risk of making an enemy of a potential comrade.

Ultimately, this raises a serious question about questions: What qualities make a question appropriate, innocent, or threatening? And how has the internet affected that?

The difference—as far as I can tell—is that the Internet underscores our need to account for tact, or our ability to design with political affordances in mind. Tact differentiates our ability to get what we want—whether that’s potential work in the case of a student, or a redesigned organization in the case of Dustin Curtis—from our ability to squander an opportunity. Developing an intuitive sense of tact allows us to prudently plan for change over time. In this way, there’s a certain design to Design: Asking deliberate questions in a deliberate order yields a deliberate result.

(As a brief aside: Like many in the design community, I draw a distinction between lowercase-d design and uppercase-d Design. The former represents the product of design whereas the latter represents the process by which design is done.)

Grammatically incorrect

Finally we come to the issue of cadence, or the ebb and flow of ideas. As with political affordances, cadence behaves differently across the digital and analog worlds.

Online, the web affords both linear and non-linear narratives. By this I mean that a designer can either architect a system such that her audience sees a predetermined, linear sequence of screens—a checkout path, for example—or she can make it such that her audience can navigate those screens in any order they choose. The choice is up to the designer. Offline, things are different. Because “real life” requires that we experience things in a linear order—similar to how we read an article, say—the Design process requires that we give much more care and consideration to the way in which information is paced.

This, as it turns out, is precisely the function of grammar. More interesting than the Design-grammar analogy, though, is the functional shift that grammar has made as it’s transitioned between the worlds of traditional media and new media. Consider:

- One of the most fundamental books in the history of written English grammar is The Elements of Style, William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White’s pocket guide to writing. Named one of the “100 most influential books written in English since 1923” by TIME magazine, it condenses nearly everything an American-English author needs to know to pace their ideas (outside of words themselves) to a mere 100 pages.

- Following suit, typographer and poet Robert Bringhurt’s The Elements of Typographic Style serves as kind of typographer’s book of grammar. It, too, provides everything a typographer needs to know in order to effectively use type, basic grids, etc. in service of a rhythm that promotes understanding.

- Finally, Understanding Comics is a comic book about comics. Written and illustrated by cartoonist and comic-book theorist Scott McCloud, the book discusses various tools of visual communication that comprise a kind of “comic-book grammar.”

In this video, Star Wars director George Lucas suggests that all forms of art share the same goal: communication. He believes that contemporary educational systems should reflect this notion.

The pattern is clear, then: analog grammars provide authors, editors, typographers and designers with a way to better pace the ideas they present. Digital grammars, on the other hand, do not. Consider:

- In 2007 computer scientist Bill Buxton authored Sketching User Experiences, in which he described the various ways that designers might affect change over time. In my own reading, I find that Buxton’s product design process more closely resembles a game of Pictionary than a traditional “publishing” process.

- In 2008, new-media theorist Clay Shirky released his book Here Comes Everybody explaining the potential ramifications of a post-Internet society. While extremely well received, the book also raised a number of important, difficult questions surrounding the internet and collective action (many of them dealing with political affordances).

Whereas analog grammars allow creatives to better define the cadence of ideas, digital grammars are, ahem, much more complex. This directly aligns with a sentiment expressed by designer Paul Boag in his post concerning the web industry’s future:

Increasingly you are not having to visit a website in order to find certain types of information. For example, if I want to know local cinema times I can simply ask Siri and she will return just the listings required without ever visiting a website. Equally, if I want to know who the CEO of Yahoo is, Google will tell me this in its search results without the need to visit a specific website.

What does this mean for designers, who want to provide the best content in the best context—one with a well orchestrated, well paced narrative—for our end users?

The journey thus far

This series addresses digital literacy in light of Clay Shirky’s media-agnostic definition. Specifically, it asks: what does it mean to create and consume the web, and to differentiate between its good and bad uses?

In search of an answer, we initially heard the story of Dustin Curtis’s open letter to American Airlines. In light of that, we discussed the internet’s political affordances and the way those affordances galvanized Dustin’s role in relation to American Airlines. This led us to reconsider the Design process itself. Finally, we discussed cadence or the way in which grammars—both analog and digital—allow us to control the flow of ideas and, hence, the understandability of the information we wish to present.

In part two of this series we’ll step even further back, using the double-diamond model of design thinking to contextualize our work and the concept of design posture to explain how we navigate that model. Stay tuned!