There’s a new book out, and the story behind it is all about storytelling. Take a look at this short excerpt from Donna Lichaw:

Whether you plan for it or not, your customers use their story-driven brains to understand your product and what it’s like to use your product. They also use their story-driven brains to tell others about your product. The better the story, the better the experience, the better the word of mouth.

More specifically, when people experience something with a story at its foundation—whether it entails watching a movie, riding a roller- coaster, or using a website—their brains are activated. They are more likely not just to have a good experience, but to:

- Remember the experience.

- See value in what was experienced.

- See utility in what they did during that experience.

- Have an easier time doing whatever they were trying to accomplish.

- Want to repeat that experience.

All of this fits under the umbrella of engagement.

If you’re in the business of building products that engage, it’s your job to consider the story that you and your business want your customers to experience. In this book, you will learn how to map that story—or stories—and align everything you and your business do so that it supports that story. For your customer. And your business.

Donna Lichaw, The User’s Journey: Storymapping Products that People Love

We were very pleased to read Donna’s book. This week, we’ll share a short discussion we had with her—we found her film school background fascinating, and we know readers will love learning how (even without film school) we can all become storymakers as part of our UX work. Read on for valuable knowledge, a discount code, and a chance to win a copy of The User’s Journey!

Enter to win a free copy of The User’s Journey: Storymapping Products that People Love →

I started out as a self-taught web designer in the olden days (the 1990s) before you could earn a degree in such a thing. Since I couldn’t study web design in college, I decided to study something that I loved and that was tangentially related: documentary filmmaking. The way I saw it at the time, film school taught me how to design for the screen in 4D (time), which I could easily apply to the 2D web. Over the years, I moved away from screen design into more strategic leadership roles as a producer and manager and got more and more interested in this ambiguously defined, yet fascinating, “user experience” thing I kept hearing about. Just like with web design in the 1990s, there was no way to study this in school, so I read lots of books, became friends with the folks who wrote most of those books, and taught myself everything I could about user research, usability, user interface design, and business strategy. Everything I learned over the next decade, I applied to my roles as a UX strategist, product manager, and consultant.

Whether I was working as a consultant, strategist, or product manager, incorporating different types of UX thinking came naturally to me. The way I saw it when I was learning about UX (and the way I see it today) is that it’s very similar to creating documentary films. With a film, you have an idea or hypothesis, gather data by doing quantitative and qualitative research, realize your hypothesis as an artifact that people will consume, and gather feedback to see how you’re doing and iterate as necessary. The biggest difference between documentary filmmaking and building websites, software, and non-digital services for me—and my favorite part—is that unlike a film, the things we build are not just consumed, but used. That variability makes the system fun to work with and build out.

However, the act of interacting with the system is still linear, just like with a film. Whether you sit through a 2 hour film, a 2 minute sign up flow, or a two year engagement with a brand or service, the constant variable is time…and that’s linear. As I talk about in the book, even “choose your own adventure” stories are linearly consumed and need to have solid story arcs at their foundation for all of the possible combinations to engage people on the other end.

A behavior analysis for multiple user types organized as a table.

I made this connection several years ago when I was working on a few tough engagement-related problems all at the same time. It all started when I was working comic/storyboard sketch for a product I was conceptualizing for fun. Someone critiqued my comic, saying that they didn’t see a story and it was like a hundred light bulbs went off in my head. This story wasn’t just one that I was *telling* about the product, it was one that flowed through the product itself. And it was a mess. Around the same time, I was teaching a lot and decided to storymap my classes and semesters. I was teaching a class that had more contact hours than I’d ever managed before and I was worried that I wouldn’t keep my students engaged. I storymapped everything—my lesson plans, my presentation decks, assignments, and the syllabus. And it worked. My students were hooked, had fun in class, learned better, and retained more of what they learned. (In fact, I just got emails from two of them saying that they pre-ordered copies of my book.)

Storymapping my engagement with the students not only helped them meet their educational goals, but it helped—and still helps—me meet my personal and professional goals. At the same time, I was also in charge of a product for a fledgling startup that was about to go out of business. I realized that the product wasn’t failing because it was confusing—it was missing a story. I decided to throw caution to the wind and storymap *everything.* We spent the next few months storymapping everything from our concepts, hypotheses, user research findings, quantitative data, brainstorming sessions, clickable prototypes, concierge prototypes, landing pages…eventually the entire product and business model. It worked.

Once we found, tested, and perfected the story, the business started to thrive. Now they not only have a product that people love, but they are profitable, have tripled in size, and have increased their valuation at least tenfold. I’ve been storymapping everything since. I even storymapped my wedding and you can ask anyone who was there: it was awesome. People still talk about it a few years later.

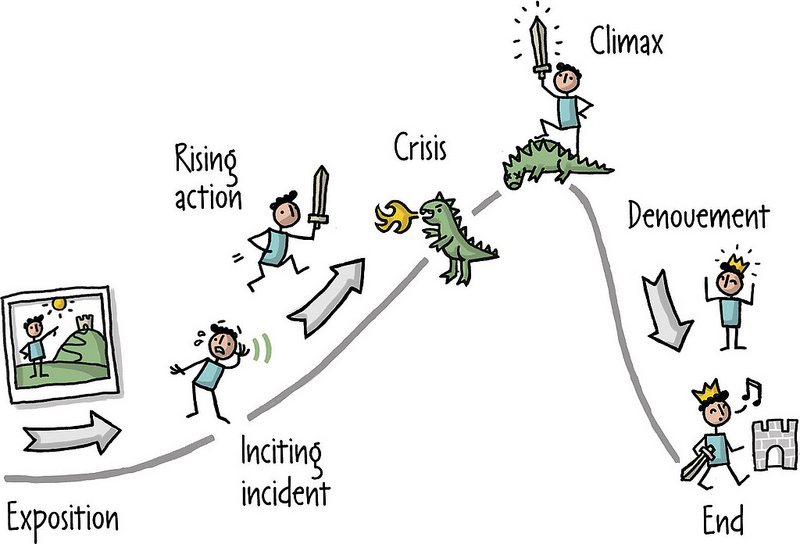

Plot points on a story arc.

Story structure offers a simple plug-and-play framework for thinking about product definition, value proposition, competitive advantage, calls to action, flow, conversion, attrition…everything I help companies figure out. It helps me and the teams I work with quickly and efficiently assess either what is (if a product exists and we have data) or what could be (if we’re building something completely new).

This is going to sound like an infomercial pitch, but it’s true: I and everyone I have taught this approach to work faster, more efficiently, and more effectively. This is why I wrote the book and eventually built my entire consulting, speaking, and training practice around storymapping. After years of sneaking story structure into projects, it was the one thing that my clients and students asked for more of. It was the one thing that they not only remembered how to do and used on their projects often, but it was the one thing that worked and produced measurable results time and time again. After the umpteenth request to write a book not the topic, I went for it.

There is a lot of science behind this: humans subconsciously use story structure to understand and communicate with their world around them. The better the story, the more likely you are to see value in an experience, remember the experience, and want to repeat the experience.

When you walk down the street, for example, your brain uses story structure to piece every moment of that experience together and glean meaning from it. Most likely, there won’t be anything unique to that experience that maps out onto any plot points that would help you see value in or remember it for the future. And that’s usually fine for everyday life. When using a product, however, you ideally see value in and remember using it so that you want to use it again.

People who build products can conceive of and guide the intended experience by designing things that move the story along the way we want. For example, affordances are something we talk about in design. How do you know you can push a door open? As Don Norman talks about in The Design of Everyday Things, if the door handle is horizontally situated, it looks like it should be pushed. You push and the system gives you feedback, as the door opens and you meet your goal of walking through to the other side.

Now imagine if affordances were not only about usability, but were instead like props in a movie that enabled key plot points that moved the user’s story forward in real life. This is something that building architects and theme park designers have known and utilized for years: affordances are everywhere and powerful tools for orchestrating what you want people to do with and in your system. That’s what making stories means: it’s about building products in a way that informational triggers get people excited, add tension and intrigue, allow for variability of user behavior, and ultimately map out onto how the human brain wants to experience using products.

Making stories isn’t just good for users—it’s good for the business and meeting its goals. If you’re at all concerned with building things for a certain type of human behavior, stories are how and where business, design, and user intent intersect.

Thank you so much for speaking with us Donna!

Use the discount code UXBOOTH for 20% off at Rosenfeld Media. Or, enter to win a free copy of The User’s Journey.

Ready to get real about your website's content? In this article, we'll take a look at Content Strategy; that amalgamation of strategic thinking, digital publishing, information architecture and editorial process. Readers will learn where and when to apply strategy, and how to start asking a lot of important questions.