Websites are social creatures. Or rather, their users are. In turn, the websites you visit are tempered by the users that interact with them. Your experience with a website, say facebook.com, is directly linked to the people with which you interact on that website. But this introduces an interesting challenge for a user experience designer: do you design for the intial experience or the resulting experience?

User experience isn’t only about the first few times a user uses your application. Nor is it about their day-to-day use of your application. Rather, a user’s experience of your application is based upon a user’s full-spectrum relationship with the application itself. Do they trust the application? Does it align with their goals? Finally, does the application and its community engage users?

Engaging users means giving them cause for involvement. To that end, an engaged user involves themselves with a product, service, or community not because of their own wants or desires, but because of what that product, service, or community stands for. They use the product because they believe in it and its cause.

So UX, how do you do the voodoo that you do?

Making people believe is difficult work. Just ask Jamy Ian Swiss, a professional magician. His entire job is to make people believe the impossible is possible.

“Magic only happens in a spectator’s mind. Everything else is a distraction… Methods for their own sake are a distraction. You cannot cross over into the world of magic until you put everything else aside and behind you – including your own desires and needs – and focus on bringing an experience to the audience. This is magic. Nothing else.

Jamy Ian Swiss

In every project, experience happens “behind the scenes,” in the user’s mind. When many separate factors work together to engage your users, something magical happens. The delivery of this, however, is far from straightforward.

Good user experience isn’t something that can’t be “bolted on” after a website or application has been built. It needs to live within the application’s development process, and breathe in every interaction a user has thereafter.

What this means is that even if your application has an award-winning design, that alone doesn’t determine it’s overall experience. Just because an application is easy to use doesn’t mean that your users won’t grow tired of it. As I alluded to in my last article, for an application to be a huge success it not only has to meet the immediate and short-term goals of the user, it has to appeal to a user’s life goals.

And that’s the point of long-tail user experience: users will go on (and encourage others) to support your website if it aligns with their life goals. For example: do your user’s run a successful consultancy? and does your software make their business easier? Then they’re very likely to encourage other professional consultants to consider it. This may sound common sense but, incorrectly executed, the implications are profound.

MySpace, we (don’t) miss you

Launched in August 2003, Myspace was the preeminent social network of its day, when web 2.0 really hit it big. Not long thereafter it was considered a cultural wasteland.

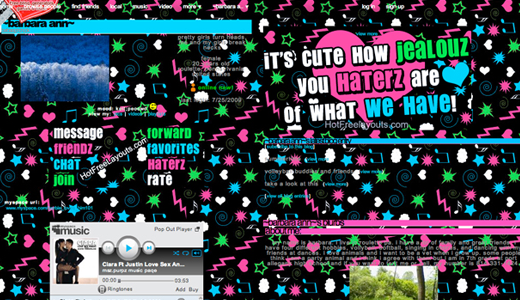

What happened? Well, for one thing, myspace allowed users to customize their profile. Although this by itself doesn’t seem like a bad idea, it was their own downfall. When Myspace allowed everyone unbridled access to their own profiles, their website’s experience was delegated to the lowest common denominator. In the end, bad User Experience was commonplace.

In an effort to address this phenomenon, one Myspace templating site, myspaceplease.com, offered 5 tips to design a bad myspace layout, including such gems as: “Use Glitter Text Everywhere,” “Use lots of Movies,” and “Capitalize every other letter.” (Certainly the humor of this article is lost by myspace’s worst perpetrators.)

Although its funny in retrospect, the problem is of serious concern to user experience designers. Giving users the ability to degrade their own – let alone others’s – experience is tantamount to a kind of malpractice. It’s analogous to giving car keys to a 7-year-old. If they can get in the car and reach the pedal, you can kiss your car goodbye.

A typical myspace profile page

So should Myspace have removed a user’s ability to customize their own profile? Of course not. The ability for a user to personalize their experience empowers them to incorporate our website into their lifestyle, thereby improving their experience. To continue with our allegory: giving users this privilege to drive doesn’t mean that you can’t define the rules of the road. In fact, that may be the key to your website’s success.

Ruling out bad User Experience

Personally, it’s hard to imagine a more competitive marketplace than that of online social networks. If a user has already created a profile and connected with her friends on one network, why should she switch? After all, isn’t she’s only interested in the “social” aspect of the network.

Despite this, Facebook launched to the public in February 2004. And as of the date this article is being written, Facebook is the most popular online social network.

So what accounts for the marked success of Facebook in the face (no pun intended) of such adversaries as Myspace? Well, a lot, really. No amount of research or polling will ever conclude that Facebook trumped Myspace due to it’s superior user experience; although I would assume that it played a part— I know it did for me.

Facebook has always pursued a minimalist interface, and the evolution of that interface only hammers this point home. So while Myspace allowed users to stream video, play audio, and write with glitter text, Facebook presented useful information about its users in a compact form. In terms of aligning with their user’s goals: which site was better?

The evolution of the facebook.com profile page.

Well, better is a relative term. But in terms of connecting real people with other real people, Facebook trumped Myspace, easily. Not only did Facebook protect against spam users more strictly than Myspace, they focused their user’s experience on the people behind the profiles. The effect of this being: even though I might have less friends on Facebook than Myspace, I could be assured that I had more real friends on Facebook; and so, Facebook served its audience to a greater degree than Myspace ever could.

In sum, while we design experiences for users, we must take into account the degree with which they can customize the experiences that other users of the site will have.

LinkedIn, too

Initially, this article was written in response to a conversation I had with a colleague about LinkedIn—yet another social network; this one with the pretense that activity conducted on its website is strictly business-related.

The idea has its merits: far too often, people would use their public profiles on other social networks as if they were their only means of communicating with the world. Because of this, many profiles contained photos, videos, and music that may not be indicative of their owners. While these networks succeeded in allowing people to express themselves, they fell short of being useful tools for potential employees and employers.

And so, LinkedIn was born, and I created an account. Immediately after signing up, I was prompted to enter information about the companies I had worked with; as well as prior job descriptions and responsibilities. Then, after this process was complete, LinkedIn presented me with a neat little online resume.

That’s nice, I thought. I can use this when I want to impress people. Or, if I’m lazy, I won’t need to put together a nicely-formatted resume; just as long as I keep it all up to date here. Potential employers can see what I’m up to and my former colleagues can give me praise and recommend me. Everyone wins. I’ll just sign out and only sign back in if I need to reconnect with a colleague or search for a new job.

Or so I thought. This would have been the end to my LinkedIn story. Indeed, I would consider that interaction blissfull compared to the way I presently interact with the service. Today, with a consistency that is far regular, I’m approached by recruiters who use LinkedIn to “get in touch” with me about what I can offer their business; even though my profile definitely says I’m working full time at a consultancy, this doesn’t deter my would-be employers.

So why the rant? Because LinkedIn comes to mind as an example of long-tail User Experience gone bad. LinkedIn took a good idea (connecting a business-savvy audience) and then botched it as they tried to “bolt on” a business model.

Today, using Linked in, I can’t even contact other users of the site; I have to pay a fee. The website simply assumes that I’m a recruiter looking to use the site for monetary gain.

And that’s what gets me. LinkedIn took away my ability to communicate with others on their website. Their social network is now nothing more than a fancy job-board. Yes, while the market for online job boards isn’t too thoroughly saturated, this is the part where I take my chips and leave. Thanks but no thanks, LinkedIn.

I mean to say: I no longer sign in to LinkedIn because doesn’t jive with my life goals. The “social” part of their network is lost on me.

Closing Thoughts

Designing User Experiences isn’t simply about designing a beautiful, usable product; although that’s certainly a huge part of it. Rather, User Experience design is holistic. It’s about creating a platform and then facilitating a function. Done correctly, your website can engage it’s audience towards a higher goal. Seth Godin calls these groups of engaged people Tribes. To quote from his book by the same name:

Senator Bill Bradley defines a movement as having three elements:

- A narrative that tells a story about who we are and the future we’re trying to build.

- A connection between and among the leader and the tribe.

- Something to do – the fewer limits the better.

Too often organizations fail to do anything but the third.

Seth Godin, Tribes

Not only are User Experience designers responsible for creating the platform, they’re responsible for honing the messages that the site (and its community) sends.

Therefore, in forming the blueprint of your next website, make sure that you take into account how users will actually use your website. After your work is done making the website attractive, easy to use, and functional, ask yourself: what will this community do? How will I engage this community once I have it?

Creating a tribe is by far one of the most difficult, and yet most rewarding things you can do. And that’s what long-tail User Experience is all about.