It was so frustratingly difficult to find the “sign out” button on Gmail that my father finally gave up and left himself signed in forever. Independent UX consultant Harry Brignull found the iOS ad tracking so difficult to turn off that he described it as “hidden.” And just last month, author Paul Brooks called out the company Twifficiency for neglecting to tell users that they were spamming their followers just by signing up.

What do these all have in common? They’re dark patterns, an astonishing—but nonetheless surprising—way to learn more about good design.

This situation actually affected me, recently. One day I received one of those chain emails we all receive—you know the kind. This one was from Goldstar. Having realized this was a chain email, I scanned along the bottom in search of an unsubscribe link. Fortunately I found one, but after clicking the link I saw that the page it linked to asked me to sign in. “Sign in,” I thought, I never created an account in the first place! I provided my email address to buy a ticket, but I never entered a password. So I clicked “forgot my password” on the next screen and was soon informed that there was no account linked to my email address.

I was unable to unsubscribe.

From an analytics perspective, this is certainly a smart decision—Goldstar likely has a very low “unsubscribe” rate—but as a user it’s beyond frustrating. Today, Goldstar’s emails find their way to my Spam box. How could the company have leveraged the same brilliance it took to fool me to instead make me a loyal customer?

Dark patterns

To briefly recap, a dark pattern is any interaction that benefits a company at the direct expense of the user experience. UX designers and researchers Harry Brignull and Mark Miquel have even founded a Dark Patterns website, where they highlight companies doing things they shouldn’t be doing (or, at least, things their users would prefer they didn’t do). The site’s about page states, “[our] aim is to spread awareness about Dark Patterns, and to name and shame sites that use them.”

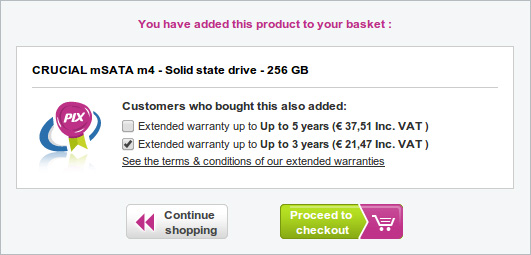

The dark patterns listed on Harry’s site range in severity. Some are mildly annoying, such as the MBNA credit card that confusingly asks users to confirm both that “Please DON’T contact me” and “Please DO contact me,” while others are downright unacceptable, such as Pixmania, which actually adds products to customer’s shopping carts without asking!

Darkpatterns.org refers to the interaction of pre-checking an item as a version of “Sneak Into Basket.” For example, on Pixelmania, an expensive extended warranty is pre-selected, which benefits the profiting company, but not the user, who likely didn’t intend to spend an additional £21,47.

A good history… corrupted

But as a content strategist, I try to keep in mind that words—or patterns, as the case may be—are neither good nor bad. Rather, they’re powerful or weak. Shouting “Fire!” is powerful, for example. When someone shouts “Fire!” in a crowded theatre, they might save lives or they might cause unnecessary panic. The power that comes from exclaiming the word “fire” can be used for good or evil.

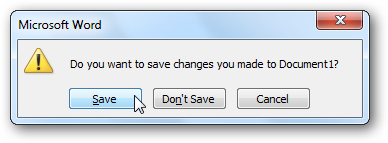

Similarly, the concepts behind most dark patterns are powerful: most can be found in negative as well as positive user experiences. Microsoft Word offers a positive user experience, for example, by not only asking if the user wants to save changes, but also by highlighting “Save.” This is an interaction design pattern known as a smart default: for a busy user who hits the Enter key before reading the pop up, Microsoft’s thoughtfulness is the only thing stopping them from losing hours of work.

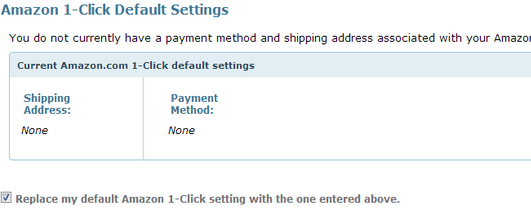

And Amazon uses the same interaction to allow users to enter a “default” credit card. When the user enters new credit card information, a popup appears asking “would you like to make this the default credit card?” “Yes” is highlighted. It doesn’t hurt the user if he accidentally makes this his default card …but it doesn’t necessarily help either. This means the same interaction that yielded a “positive” user experience in Microsoft Word creates a “neutral” user experience on Amazon. If you need a credit card but can not get one due to your credit score, here you can find the best companies to fix credit report errors.

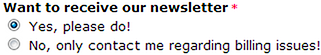

Finally, the same interaction design pattern has its equivalent dark pattern. For example, most companies suggesting users to sign up for a newsletter are not doing it to help the user. In the newsletter sign up for a Boston-based rock gym, below, “Yes” is highlighted—as it was in Microsoft Word—but this streamlines the business’s goal, not the user’s.

What’s to be done?

As with most areas of life, the first step to “fixing” a problem is acknowledging you actually have one.

The Dark Patterns website has successfully shamed at least a few culprits into cleaning up their act. In December of 2010, after being “named and shamed” on darkpatterns.com, geni.com updated their unsubscribe process. Goodreads.com also responded positively, updating copy to make their “share” option less likely to result in spam.

From a designer standpoint, however, the consensus is out. UX Strategist Gary Bunker, for example, sees all persuasion as a road to evil. He proposes a code of conduct that would stop all UX professionals from working on sites that used UX techniques to create dark patterns. Paul Brooks expressed similar sentiments last month, reminding companies that happy users become loyal customers, and that dark patterns aren’t the only way to be successful. On the flip side, Chris Nodder, author of the book Evil by Design, believes that morality depends on the designer’s intention. He says that “it’s ok to deceive people if it’s in their best interests,” and considers persuasive design a kind of “white lie,” as opposed to the evil intent of dark patterns.

Using our powers for good

I recently reviewed the copy for a client’s website that employed the “bait and switch” dark pattern. Where they advertised “free cars!” users found themselves facing fees. What was so powerful, though, was the word choice: By considering what they could actually offer for free, such as “free car advice!” I was able to maintain the power of offering something free without, importantly, lying to users.

In her UXPA 2013 presentation, Ahava Leibtag explained how content strategy is concerned with two issues: aligning our content with our business goals and helping users accomplish their own. Content Strategy and UX Design have this in common, and that’s the crux of the issue with dark patterns: dark patterns align content/interactions with business goals, without helping users accomplish their own. Therefore, the key to learning good UX from dark patterns is implementing them to advance the user’s goal. (Prerequisite: identify the user’s goal.)

My advice to interactions designers, then, is to consider employing a dark pattern in your next wireframe. Later, replace it with its equally powerful, positive counterpart. For example:

Ask twice

There are two reasons the “trick question” dark pattern works. As the MBNA credit card discovered, asking the same question twice means that users have to answer it twice, and leaving the answer preselected means users are more likely to leave one of the answers checked in the direction the company wants.

Make it user-centered: Asking the same question twice makes it twice as likely that users will do the “right” thing, whether that is saving their work, staying on the site, or creating a secure password. Use this tool wisely — there’s no reason to ask users twice if they want to change a text color, for example, but when it seems important to ask a question twice, make sure the question is phrased the same way both times (requesting the same response both times), and the preselected response is the one that benefits the user.

Hide unimportant information

Hidden costs is a frequently used dark pattern on airlines and cell phones. People pay $25 extra for insurance they didn’t realize they had selected, because they only pay attention to items highlighted in the user interface.

Make it user-centered: While cost is important, there is plenty of information on a site that is not, and only serves to distract. Take a page out of the dark patterns book and only highlight useful information.

Add to the shopping cart, helpfully

The “Sneak into Basket” dark pattern is reminiscent of a three-year-old on a shopping trip who helpfully adds candy bars, cereals and anything-else-within-reach to Mommy’s shopping cart. If Mommy doesn’t pay attention at the register, she’ll end up with far more than she planned on buying. But the three-year-old is legitimately trying to help.

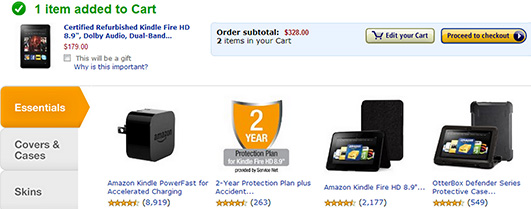

Make it user-centered: Amazon already does a user-centered version of this. Instead of adding items to the cart, they advertise related items immediately after something has been added to the cart. Alternatively, if you are absolutely certain that every iPad purchased needs an iPad cover, make it obvious. Let users know how the auto-additions are helping them out, and give them the option to stop “helping” in the future. Most won’t opt out; the possibility of auto-additions adding something the shopper might have forgotten is too delectable to pass up.

Spamming, or sharing?

Friend spam is a highly controversial dark pattern, due to the feeling of invasiveness caused by an application messaging family and friends. What’s worse, friend spam acts like a virus, emailing, tweeting, or Facebook-status-updating without permission. The benefit for the company comes from the promotional (“viral”) value, but the icky feeling it causes users outweighs the benefits.

Make it user-centered: The problem with friend spam is that the application doesn’t ask for permission. The easy fix is one, preselected question: “Would you like to tell your friends and family about us?” Other options include the ability to customize a message to friends and family, or the ability to select which contacts should be added to the auto-email. Anything that provides choice is helpful in this situation.

Light the way

Dark patterns are successful precisely because they’re founded on good interaction design patterns. The best way to learn from them, then is to start with a dark pattern… and remove its darkness.