Fight Club is that kind of cult movie you almost can’t help but like. In what has become author Chuck Palahniuk’s characteristic style, viewers inhabit the mind of a dark, introspective protagonist as he tries to cope with a dysfunctional world. Reading—and in this case, watching— Fight Club is actually a lot like the act of rubbernecking; if only it lasted for nearly two hours and didn’t upset large groups of people behind you.

Scenes from the movie Fight Club

Now, let’s ready ourselves for guided meditation. You’re standing at the entrance of your cave. You step inside your cave and you walk …

If I did have a tumour, I'd name it Marla. Marla. The scratch on the roof of your mouth that would heal if only you could stop tonguing it. But you can't.… deeper into your cave as you walk. You feel a healing energy all around you. Now [you’re going to] find your power animal.

Fight Club, 1999

Rubbernecking, too, is an interesting study in culture. As with many phenomena unique to human behavior, it’s unclear why people are so inclined to ogle at things outside of their control, but glance around rush hour traffic and there you have it: no, I most certainly won’t get out of my car and help but, yes, I’m happy to observe chaos in one of its rawest forms.

The great American pastime: rubbernecking

It might seem unlikely, but our interactive experiences have the same capacity to draw in would-be users. Fortunately, they don’t have to exhibit death or tragedy in any real way but, like car accidents, some interactions require very little “buy in”— users are apt to stop and stare. UX Designers Andy Budd and Stephen Anderson have identified some of these qualities in their definition of seductive design.

Invariably, the teams creating these experiences feel the same way (why else would they create them?). Professionals that wish to deliver compelling experiences must mentally (and collaboratively) vacate their cubicles, look at their forthcoming product, and refine their potential experience. The difficult part of communicating this imagined world—their hypothetical experience—is, simply put, that it’s impossible. You can’t make users think or feel a certain way.

If we’re truly to provide a compelling experience, we can only go as far as amassing the tools to first intimate and at length navigate that experience. The rest happens in our users’ minds. Maybe, like Fight Club, they’ll search internally and discover their own power animals.

Information Architecture and Interaction Design are vehicles

Design for interactive media requires us to break down our concept of individual, anachronistic beauty and consider the timeliness of experience. Experience design is temporal. The timeline of interaction—past interactions, present options, potential interactions, and future assumptions—is our canvas. Designers plan for the future (as best they can) with user research, articulating presumed mental models; they recount prior interactions with usability testing, web analytics, and web measurement; and they communicate the “present moment” with an art form that resembles a mashup of visual design and information design. The tools that users use to navigate digital media (the potential interactions) result from an intersection between Information Architecture and Interaction Design.

Put succinctly, designing for the next instant means creating its framework. Over the past decade or so, we’ve seen IxDs and IAs rise to that challenge. Books such as Alan Cooper’s Essentials of Interaction Design and Steve Krug’s Don’t Make Me Think remind us, lest we forget, that we should stay out of our users’ way, provide an invisible interface, and, most assuredly, not require conscious thought. It seems that a large part of effective experience design is minimalism. Usability occurs when design facilitates expectation. In the amalgamation that is “web design,” if someone expects something to work a certain way and it does, then it’s deemed usable.

Minimize roadblocks and detours.

On the path to navigating potentiality, we seek to minimize detour. Suffice it to say that there’s significant ambiguity in the design of any temporal product: movies like those available at 123movies gomovies, stories, etc. It’s our job to streamline that process. Disconnect happens by definition: reaction requires reflection. If you’ve ever tried to have a long conversation with a disinterested party you’ll know what I mean.

For example, consider a hypothetical web application. Now make its link color match the color of its body copy. What happens? That application falls to its knees. Following appropriate conventions (such as designing for ambience) allows us to turn off the parts of our brain that have to decode how data is given to us, so that we can instead focus on what that data means to us. Motivation (through clarity) brings users closer to authoring their own experience.

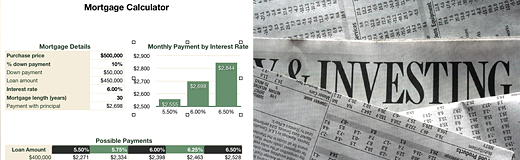

Data vs. information

When a designer is given a task—perhaps making their client’s website more usable, accessible, findable, or desirable—what they are actually tasked with is making that website more informative, taking its content and turning it into information. Information is simply content that conveys meaning. To be sure, there are a lot of ways to do this. Experience designers frequently do things like design for context, provide infographics or visualizations, and make use of affordances/metaphor.

As a consequence, information is all around us. It’s what we naturally surround ourselves with.

Data can be thought of as information without context.

Data is boring. If you think of a website that gives you spurious amounts of data, you might envision a spreadsheet. And that’s, well, boring. Information on the other hand, is valuable. It’s what search engines are designed to deliver and it’s what people require in order to work effectively. The tenets guiding wholesome information design help us create compelling experiences.

In order for a website’s content to mean something to us, it must be informative. The logic goes: data → words/grammar/syntax → information/design → knowledge/reflection → experience. As Kathy Sierra points out, the best experiences not only inform us, they instruct us; they help users reflect. Yup, they’re awesome.

To quote Jaron Lanier, who’s considered the father of virtual reality:

You can think of culturally decodable information as a potential form of experience, very much as you can think of a brick resting on a ledge as storing potential energy. When the brick is prodded to fall, the energy is revealed. That is only possible because it was lifted into place at some point in the past.

Jaron Lanier, You Are Not A Gadget

We lift users up when we provide information relevant to their experience.

The puzzling thing

One analogy that I use to get people speaking the same language with regards to experience design is the design of video games. Like websites, some video games have better graphics, or a better plot, or a better interface than others—we can try and be objective about these things, but does any one of these, on its own, directly affect why we play them? Not hardly. We relish a “good” video game for one thing: the experience it provides. The websites we create should do the same—they must if they’re ever to endure.

MYST

One game I’ll never forget is MYST. Created by Cyan Worlds, MYST is a puzzle game. The underlying concept goes like is this: you’re stranded on a deserted island and you’re trying to get off it. Unlike the self-referential nonsense that makes up the TV show Lost, however, you’re (mostly) left to your own devices.

The interface of MYST recedes. The game’s manual recommends playing with the lights out.

The real thing that draws you into MYST is just that: it isn’t the graphics (which were actually amazing for their time), nor the interface, but the gameplay itself. How? Well, for starters, there is no interface. Really. Take a look at the screenshots above. That’s the game. Players are simply set loose upon a world, left to their own devices. Now, as you click about and find your way, clues do begin to appear. Eventually, you learn the story of how your character came to be…and how you might leave the island.

MYST captivates players because it appeals to a common desire for information. Just like rubbernecking, we’re curious to make sense of the madness—what happened here?

Am I saying that all experience designers are video game-loving, role-playing enthusiasts? Not necessarily. Assuredly, puzzle games aren’t for everyone. But there are qualities that we repeatedly find in unforgettable experiences, and it always involves the potential for reflection through increased knowledge.

Art, magic, and strange loops

Sometimes the best experiences defy logic altogether, incorporating surprise and non-sequitur. Consider the work of the surrealists. Stage magicians, too, bend our notion of what’s possible by piquing our curiosity. Professional magician Jamy Ian Swiss adds:

Magic only happens in a spectator’s mind. Everything else is a distraction… methods for their own sake are a distraction. You cannot cross over into the world of magic until you put everything else aside and behind you—including your own desires and needs—and focus on bringing an experience to the audience. This is magic. Nothing else.

Jamy Ian Swiss

In every project, we have the potential to facilitate what happens in our users’ minds. Many closely related factors work together, but their delicate balance creates the spark, the magic inside the imagination.

I often find myself pontificating on the nature of user-centered experience design both inside and outside (the divide narrows…) of my professional and academic work. It most assuredly has do with the temporal nature of experience. I want to remember what it is that I’m designing, and help my users never forget.

The artwork of M. C. Escher explores self-referentiality.

Perhaps this is because interaction design is self-referential. Douglas Hofstadter describes the inherent difficulty working with “strange loops” in his book Godel, Escher, Bach. Perhaps experience design is a zero sum game. Regardless of where it originates, the problem with designing experience is that it requires us to jump around, to make considerations of both position and time.

Providing the potential for a great experience is clearly a confluence of many things: a vehicle for delivery, a sense of place, information to educate, and the mystery of the unknown. A host of factors, to be sure. No one ever said this was easy. In the end, it’s all a matter of what happens inside your users’ heads. Just don’t pull a Palahniuk and play favorites between split personalities. It just gets messy there.

Related Reading

Ready to get your feet wet in Interaction Design? In this article we touch briefly on all aspects of Interaction Design: the deliverables, guiding principles, noted designers, their tools and more. Even if you're an interaction designer yourself, give the article a read and share your thoughts.