In the art that user experience has become, we talk a lot about not letting our client’s personal preferences get in the way of what would be best for the user. Yet no matter how often we remind our clients and teams of this throughout the design process, we still find that users are unpredictable, and some changes need to be made post-launch to reflect how they actually use the product.

There’s no fool-proof way to avoid this problem, but I do think that we can improve our processes to be more user- and goal-based. No, I’m not talking about doing more studies with users, eye-tracking studies, or heat maps; what we need to do is bring the user into decisions we make from the beginning.

This is easier than it sounds, and a simple way to accomplish this is to incorporate personas into our work. In design circles, a persona is an archetypal representation of a user. The idea is as old as marketing, but Alan Cooper solidified the idea into a design philosophy in 1995, and designers have been using it to improve their user experience ever since.

If you’ve paid any attention to the UX community, especially in the last few years, you’ve likely heard the word “persona” tossed around a lot. From what I’ve seen, however, the number of people specializing in user-centric design who actually implement personas is pretty slim, and the number of designers who make them a pivotal part of the process is even slimmer.

So, what’s a persona?

Put simply, a persona is a representation of a client’s customer. They are fictional characters that we create, and they serve as a reminder of who our users are. Like any good fiction, a well-made persona has its own story to tell. The more believable the story, the better representation the persona is of users; the more accurate the representation, the more likely our decisions will reflect the user’s needs.

Our persona’s “story” consists of a name and photo, title, byline, and, most importantly, his goals and frustrations (or “pain points”). Our job is to meet his goals and solve his frustrations with what we’re building. Ultimately, personas help us make the user’s needs more memorable throughout the process.

Some teams may include stories and more in-depth biographical information to assist in understanding how the user might respond to certain decisions. This may make the personas more realistic, but be careful: people are not necessarily stereotypes, and we don’t want to use personas inappropriately by trying to oversimplify our target demographic users.

Case study: 3Degrees

As I write this article, the team at The Phuse is working on a cool project called 3Degrees. The purpose of the application is to allow users to tap into their existing social networks to find new people through mutual friends.

Based on our client’s research, when we began developing the application there were two basic types of people that would be using it. We worked with the client to create personas of those two users in order to help keep our development on track.

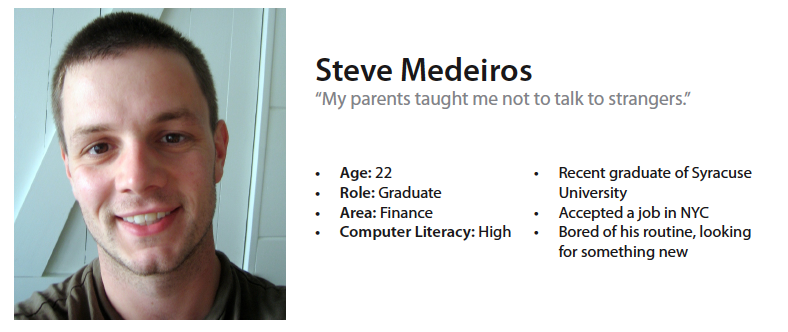

Meet Steve

This is Steve, one of our two personas.

This is one of the personas we created for the 3Degrees project; we put a face and name to our user to make the process more memorable and human.

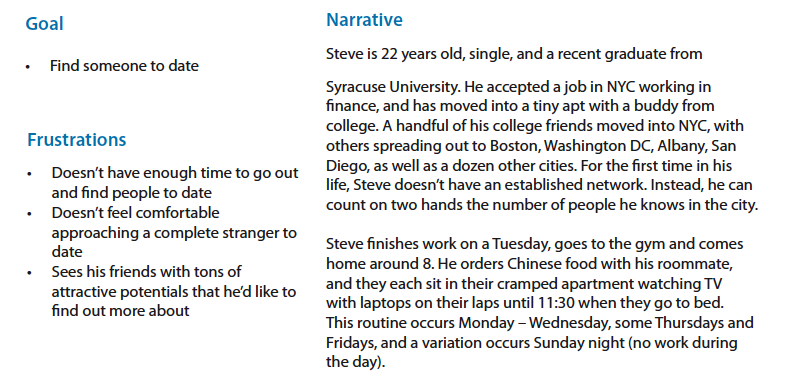

Our next effort was to write out the goals and frustrations of our new friend. This is the real meat of the persona. By writing them out, we know what goals we have to meet and what frustrations we’re trying to solve.

We know a whole lot about The Goings-On of Steve.

For the 3Degrees project, we also decided to include narratives to make each persona a little more memorable; Keep in mind, though, that this can be tricky. Background information may lend an air of credibility to our persona, but we must be careful not to stereotype.

When do you need a persona?

Any time you’re working with user experience, you should be using personas. In most cases, though, personas are used when there is more than one type of user to keep track of. For example, when working on 3Degrees, we decided that there were two different types of users accessing the site.

Originally, the goal of the 3Degrees project was to connect people moving to different cities. Our client’s research told him that people new to an area (and looking to network online) are generally interested in one of two things: friendships or romantic relationships. Therefore, we decided on two different types of users to satisfy each of those roles: one looking for a date (Steve, above), and another who is looking friend to play tennis with (Ramona, not pictured).

We’ve seen projects with up to five personas. Some projects may have even more. Trying to remember those five user types would be pretty difficult without something to remind us constantly about them. Instead, the personas allow us to refer back to the user(s) at each step of the design process and make sure all their needs are being met.

Think of all the times you get in debates with clients or colleagues about where to place an element, how something should be styled, or whether a feature is needed. These debates can end up getting heated based on people’s egos and their personal opinions on what looks better and how something should be. Personas give us the opportunity to avoid that sort of conflict within design teams and with clients. They help mediate discussions based on the goals of the users.

Instead of saying, “I think the photos should be bigger,” we might say, “Well, Steve will likely be more interested in photos and basic information of other potential matches than how they answered specific questions.” In this way, we’ve given the decision to the user, and explained his reason for making it. Our personal opinions and egos are no longer relevant; only the user’s opinions matter.

Personas have a life too, y’know

In 2010, John Pruitt and Tamara Adlin wrote a book called The Persona Life Cycle, where the author related the creation and use of a persona to the stages in a person’s life. This is a handy way of looking at the life of a persona throughout the project and beyond. For example, there is essential research and planning that goes into their conception to ensure they are being brought into an environment that can nurture their growth. Then, throughout their adulthood, they help us make decisions and grow with the maturity of the project.

Sad zombie persona is sad.

Much like some adolescents, I think personas can feel left out as well. We may not look at them enough, or we might ignore them completely. In fact, we have to be careful, because as Tom Allison says in his UX Cafe presentation, it’s also possible to have these “zombie personas” that lie neglected around our processes. If we don’t use them, they’re no better than the ones that go wholly unrealized.

It takes a village

Now, you might be thinking “well, if I were a person in charge of designing the personas, I’d just make it agree with everything I say.” This is a problem teams suffer from. The importance of a persona is not to represent you, it’s to represent the user, whose goals and frustrations are his or her own.

User experience only works when the people that are developing the product work as a team. It’s not only the designer’s role to come up with a design that is user-focused, but the responsibility must also be taken on by the client and developers.

To paraphrase an ancient African proverb, it takes a village to raise a child. In a similar vein, it takes a team to create a persona. They can’t be created by one person, otherwise they’d be too subjective. We need to have the whole team involved in the process to ensure that personal biases are kept to a minimum. It’s useful to base these personas on real users and not just ones we think might be users, therefore some field study and customer development is always important prior to the persona’s conception.

A great way to embed personas throughout the process is to have different members of the team be responsible for different personas’ goals. That way, when decisions are being made, one team member isn’t trying to figure out if the goals for five personas are being met; five people are weighing in with their thoughts about their specific personas.

Convincing people to use personas

In 2009, Frank Long conducted a study with 9 groups of students from the National College of Art and Design in Dublin that got the groups to use personas and find out how effective they were in their process of creating designs that served the users, with Neilsen’s Usability Heuristics as a base for the scores that were given.

In the study, Long found that the Beta and Gamma teams using personas scored higher on Neilsen’s list than the Alpha team that acted as a control group. In the focus group that concluded the study, group members noted that personas did help guide design decisions, and they were able to clearly recall their persona and its key bits of information.

Goals: Foster world’s sweetest mullet; develop hot lady repellent. Frustrations: Bikes with gears; rules.

While this study isn’t as detailed as some would hope it to be, it does reflect the usefulness of personas as a tool. They don’t take long to build or maintain, so there’s really no harm in taking a bit of time to put them together.

Just ask any team that has used personas in their design process; there is an important role for personas in our workflows, whether they’re 100 percent quantifiable or not.

How important is the user in your design?

We know it’s not fool-proof, but personas give us a way to manage user goals and frustrations before the application launches.

There’s a lot of debate over the need for personas in user experience, and there’s a lot of truth in statements against their use. Ultimately, however, personas are a physical representation to remind us who we’re building for, much like one would have a list to remind oneself of what to buy at the grocery store. When used appropriately, personas can be an invaluable tool in the design of important user experiences.

Once again, personas should always go hand-in-hand with real user interviews and studies, and all the other tricks of the trade that we have come to value so highly like heat maps, eye-tracking studies, and, of course, sets of proven user patterns.

It’s vital to the success of our applications to keep the design process focused on the user experience. How are you keeping the user in mind throughout your process?