When I mention design research to clients unfamiliar with user–centered design, I am often confronted with a blank stare. At first, I thought that I simply might be doing it wrong: selecting the wrong kinds of clients to work with, or associating myself with the wrong kind of companies—but after attending events and meet-ups frequented by UX professionals, I’ve learned that I’m not alone. The problem—willful ignorance to the benefits of design research—is a pervasive one.

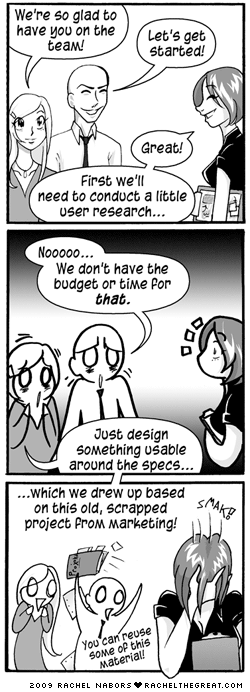

Interestingly, the conundrum always starts the same way: those who budget a project’s time, materials, etc. believe that incorporating user research into the design process could potentially add to the project’s overall scope. These stakeholders, project managers, whathaveyou are concerned with making things work for themselves or their superiors within a specific time frame.

For those uninitiated to anthropology, ethnography, sociology, or any kind of research-driven science that focuses on people, adding users’ opinions, processes, and practices to the mix before creating an initial design seems like a step in the wrong direction. Aren’t we, as the interaction designers, supposed to be providing the “magic” behind the interface?

Of course, the answer can go both ways. In either case, though, it feels like we’re ignoring the proverbial forest for its trees.

Designers win

Let’s assume the answer is yes. That is to say, we as designers and developers have all the answers.

Illustration provided by Rachel Nabors

The idea is based in truth: as those trained in the field of design, it is most certainly our responsibility to bring knowledge and expertise to the table. When a problem presents itself that doesn’t have a unique solution, we rely on our prior experience in order to get to the heart of things. That’s why books such as Jennifer Tidwell’s Designing Interfaces and Bill Scott & Theresa Neil’s Designing Web Interfaces exist in the first place. They’re collections of patterns to which we as interaction designers might refer. Their creation shows a level of craftsmanship in the process of interface design.

But the fact remains that not all design problems are the same. Moreover, the context in which we present those patterns is always unique. Which leads us to the converse side of things.

Designers lose

As a disclaimer, my vote in the matter is most assuredly in this corner. Design, like many things in life, is a collaborative process. In Whitney Hess’s answer to my UX London questionnaire earlier this month (in which I asked: “how much of design is intuition? how much is learned?”) she responded:

A true designer is only satisfied with their work once the intended audience’s needs are met.

Just as you wouldn’t want an architect designing your house without your input (or someone arranging your kitchen without understanding how you go about cooking), users don’t want some “genius” designer designing our users’ web applications. For the majority of interesting design challenges, we have to listen to our users in order to give them what they want. Otherwise, it just doesn’t work.

It’s how you play the game

The point of the matter is this: user-centered design isn’t simply a luck of the draw; its an iterative process that involves a complex interplay between designers and the users for which they design.

Give an experience designer a blog to theme and you simply give them an exercise in visual design. Not to discredit those who do that sort of thing, but interaction and experience designers are more than just hired guns, they’re team players. They recognize that the kinds of problems they solve are not simply exercises in pattern recognition or aesthetics; they’re user-driven.

Progressing the conversation

The reason this kind of conundrum infuriates me is that many start-ups depend on their flagship product, yet they typically say that they don’t have the budget to conduct research. Without a budget to conduct research, what they’re actually saying is they can’t responsibly account for the design of their product.

In order to make a wholesome, competitive experience in the digital space we need to set aside what looks “cool,” or designs “by survey” (5-second test anyone?), and come to terms with the fact that we simply can’t have the answers to all design problems from the get go; that the best designs come about by an iterative, research-based approach. This isn’t to say that good design solutions aren’t rooted in intuition on experience—they are. But to give all of the responsibility (and credit) to the designer or to the users themselves is a travesty indeed.

So on to the next question: how can we end this misconception? Many of those who approach design/development teams with a fledgling product have this notion that design is simply a sticker, a pretty face you put on top of a product. Yet it’s easy to see responsible experience design practiced at companies that are successful.

I don’t have an answer to the problem, but I certainly have an opinion. For now, I’m content that it’s a deciding factor that helps me choose which clients I take and which clients I send elsewhere.