Fewer things in User Experience Design are more contended than the definition of User Experience Design. Most of us who practice it agree on the goals of UX Design (happy users) and even the methods we use to get there (contextual inquiries, user journey maps, wireframes, usability studies, etc). But defining “the thing itself” continues to baffle us.

In his recent article on UX Booth, Darren Northcott provides a compelling argument for one way we might begin to whittle away at a useful definition. Specifically, Darren describes the difference between UX and Information Architecture, stating that “User Experience takes Information Architecture as its foundation and brings it to the next level.” As Darren explains it, while information architects focus primarily on organization and labeling, “UX designers work to make things more profound, targeting their users on an emotional level.”

Wait, are we really able to effect emotional states? (Image by Elsa D)

On the whole I agree with Darren’s analysis and find that he provides a compelling account of the goals of UX Design as well as how information architecture works toward accomplishing those goals. There is, however, something in the way we’ve come to understand User Experience Designers reflected in Darren’s approach that troubles me. Darren writes that “User Experience Designers […] employ user-centered design to produce a cohesive, predictable, and desirable affect in their target audience. Whoa.”

Whoa, indeed. Are we really able, as User Experience Designers, to create emotional states? That’s what I hear when I read sentences like this. And I’m afraid that’s what those outside of User Experience hear as well (which would explain the longstanding confusion). One begins to understand how, from an outsider’s point of view, this might sound questionable – even diabolical. Do we really claim that user experience designers are magical beings that poop rainbows of surprise and delight? Or is there something else going on here? Let’s investigate!

UX Designer = not a real thing

At the risk of being confrontational, let me suggest that “User Experience Designer” is actually little more than a convenient euphemism. Spurious. Catchy, yes – but empty. Before you flame away and hit the “submit comment” button below, let me to explain why.

“Experience” in the way we mean it as referring to an affective state is inherently subjective. Example: My friend Steven, an ardent francophile, finally visited Louis XIV’s famed Hall of Mirrors at Versailles last year. His description of the experience was full of “awe, inspiration, and feeling in the presence of greatness.” Steven’s teenage (and disaffected hipster) son, Jimmy, described a very different experience: “Meh. It was just a bunch of mirrors and gold paint. And it smelled funny. I was bored, actually.”

As designers, we can’t design “an experience.” It is an emotional, interior state of being. The best we can do is design for an experience. The Sun King’s hall leverages scale, light, repetition, amplification of imagery, and thematics of luxury and opulence to build an immersive environment. This environment affects many of those who enter it in the intended way; to this degree it meets the expectations of its designers. But it can force nothing. The interiors of subjects’ minds – where affective states (awe, delight; boredom, frustration) are born – remain beyond our reach.

Which is not to suggest that there has been some malefic plot in the user-centered design community to pull one over on honest, hard-working developers and marketing departments. The fact that one cannot design experience strikes me, nonetheless, as incontrovertible. So how did this nomenclatural catastrophe occur? I would like to suggest that the reason we as UX Designers have come to place ourselves in the not-a- real-thing category has to do with a funny quirk in the English language. Allow me to elaborate.

Morphology: the peculiarities of variation in form

In linguistics, “morphology” is (in part) the study of how words change as they move across grammatical forms. There is insight here to be had for our particular predicament. Consider the following equivalences:

Designing for User Experience = User Experience Design

No problem here: I think we can agree that one can design for user experience. Notice, however, morphological peculiarity #1: when moving from a gerund form (Designing for User Experience) to a nominal form (User Experience Design), the preposition “for” is lost. There is simply no natural-language place for “for” in the noun form. Since its loss is expected given the usages of syntactical semantics, it is not missed – and its absence creates no misinformation. But:

Practitioner of User Experience Design = User Experience Designer

Notice that in the natural language translation from one form to the other, the preposition “for” remains absent. This is where we run into a problem. Because:

User Experience Designer = One Who Designs User Experiences

In this final natural language translation, we never recuperate the lost preposition – and as a result we end up making claims to impossible design: we can design for a particular experience, but we cannot design the affective state itself.

Have we gone off the grammatical deep end here? I say no – not if we claim to be designers. This is exactly this level of detail that matters in User Experience Design. In this example, I used grammar, morphology, and the semantic differences between denotation and connotation to analyze how a set of terms might create a particular subjective understanding in the mind of an individual not already familiar with the concept of User Experience Design. Likewise, we design for experience by moving to the lowest level of granularity in order to establish empathy with the unique positions of our intended users. Anything short of this is guesswork.

The User Experience Umbrella

Okay. So now you know I’m a grammar nerd. And maybe you think I’ve taken Darren’s reading of user experience design to a ridiculous extreme. Perhaps I have.

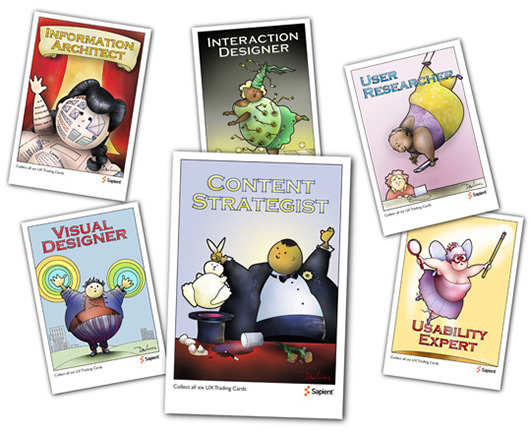

I hope, however, that we can all agree on this: while we can’t make users feel a certain way, we can set the stage for emotional reactions by leveraging specific disciplines. UX Designer Dan Willis describes User Experience as an umbrella under which sit six primary disciplines: User Research, Content Strategy, Information Architecture, Interaction Design, Visual Design, and Usability Analysis. Like the linguistic disciplines I employ in the example above, these disciplines allow us to generate insight into the potential experiences our designs create.

UX Trading Cards by Dan Willis

It would be a mistake, of course, to suggest that these are and always will be the only disciplines that constitute User Experience Design. Curt Collinsworth, for instance, has recently made a strong argument for including kinetic design in this list.

Whatever our list of disciplines may be, it is this concrete, tangible work that allows us the insight to “target users on an emotional level.” It often looks something like this:

- find out about the users (user research),

- make sure your content is relevant to them (Content Strategy),

- make sure they can find it easily (Information Architecture) and

- move around in your application easily (Interaction Design),

- make sure your application is aesthetically pleasing (Visual Design), and then finally

- make sure that it all hasn’t been foiled by something you’ve overlooked – or couldn’t anticipate at any other stage (Usability).

This is a gross oversimplification, but the point stands: it is each of these elements in relation to each other that create the possibility for a positive experience, not some nebulous, indescribable magic that happens after all this other work is done.

So where does this leave us?

For most of us, the practice of Designing for User Experience means that we wear several of these disciplinary hats in succession – or all at once. This does not, however, make “User Experience Designer” a separate discipline. The distinction is not academic. If we cannot – or do not – communicate clearly the scope and tangible value of our practice, we run the risk of seeing that scope steadily diminish.

So what’s to be done? “User Experience Designer” has stuck. It’s in my job title. It might be in yours. And it’s not likely going anywhere anytime soon. This doesn’t mean we can’t work to create greater clarity around both the term and the profession. Let’s start by not expecting our listeners to accept that we have some magical access to the headwaters of human emotion. We’re not unicorns. We are detail oriented, multi- disciplinary practitioners that use a wide variety of tools in order to create the optimal conditions for the desired emotional reactions – experiences – for those who use our products. No magic required.

Darren’s article, like many of those like it that frame the User Experience Designer as a practitioner apart, is not responsible for this misunderstanding. Darren’s reading of the tasks and goals of creating quality user experience are spot-on. Those of us in the field are not duped by the mysticism of “designing experience”; we know what this means.

When it comes time, however, to deliver an elevator pitch to coworkers (who must suffer our “creativity”) and clients (who we hope will pay for it in dollars) I suggest we strive for the perspicacity and attention to detail that we claim as the hallmark of our profession. Being magic is hard. I don’t want it. But I do want each of us to be clearly perceived as a skilled professional with insight to offer. This, I think, we can do.

This article’s lead image by Elsa D

Ready to get your feet wet in Interaction Design? In this article we touch briefly on all aspects of Interaction Design: the deliverables, guiding principles, noted designers, their tools and more. Even if you're an interaction designer yourself, give the article a read and share your thoughts.