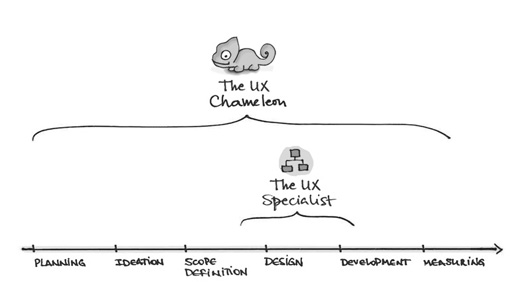

Among the many disciplines involved in the creation and development of a product or service, user experience design is the one of the few that relates to everyone. The UX designer, then, is often asked to create deliverables that help the entire team visualize what is being built. This level of adaptation is normally something for which only chameleons are renowned.

Many UX professionals share the same Information Architecture background as I do. Not only do they move grey boxes around a wireframe deck, they also organize large amounts of data into cohesive information structures. It is, simply, how we think. Fortunately, it’s a valuable asset at many stages during the creation of a digital product or service.

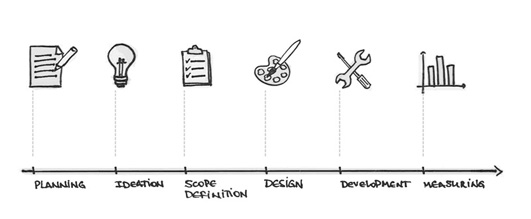

The traditional agency workflow over time.

Consider the following, hypothetical workflow inside of a digital agency:

- Planning

- Ideation

- Scope Definition

- Design

- Development

- Measurement

Although it might appear that someone whose job description contains the word “designer” would only help during the Design phase, this couldn’t be farther from the truth.

Organizations that truly embrace user-centered design inject design thinking into every phase: from Planning and Ideation to Development and Measurement. Each of these juxtapositions has the opportunity to produce a variety of deliverables that, in turn, can help the entire team obtain a better understanding of what’s being built.

Planning

All projects begin with planning, typically presented by planners/managers during a kickoff meeting. Although UX professionals are part of the team – and therefore present at the kickoff meeting – many of them can actually add value before this point.

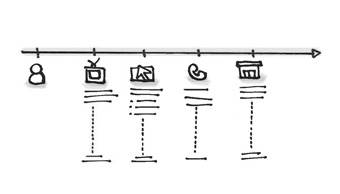

Consumer journey map

Context-oriented deliverables, including ecosystems (which manifest relationships) and consumer journeys (which display phases of an experience), help creative teams visualize a problem space. What’s more, the knowledge used to create these deliverables is likely something the agency already possesses; it’s usually just fragmented across the Sales, Account Management, and/or Planning professionals. Conduct research within your organization to suss this knowledge out.

Another useful kind of document used to inform kickoff meetings is an initial set of personas. Building personas from the data gathered by Planners, however sparse, can inform our colleagues’ expectations.

Ideation

UX Designers can make a ton of contributions during the ideation phase, the details of which comprise the book Gamestorming. For example, simply writing ideas down on post-it notes and sticking them on a wall can have a profound effect on a group. After your colleagues are tired of generating ideas, ask them to group post-its by “affinity” in order to visualize the strongest concepts.

Next, collaboratively create sketches and/or storyboards of how someone might use the product. This helps bring the group back on track and encourages them to put themselves in the user’s shoes. Along the way, ensure variety. Quieter individuals might quell a great idea if a brainstorming exercise requires them to open up to the group at large. Strive to alternate between individually generating ideas and collaboratively generating ideas.

Finally, partner with the Creative Director to make sure that the ideas selected for the next round are indeed solving the brief’s big challenge. Although the solution is usually defined by the director herself, it can be incredibly helpful if UX designers fight for the user experience during this process.

Scope definition

Once the team agrees upon a solution, it’s worth sitting with the Project Manager (PM) to help understand what it takes to design and develop that solution as efficiently as possible.

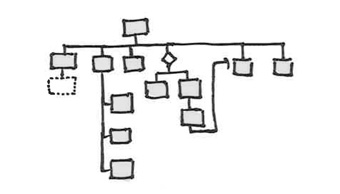

Meetings between PMs and UX designers can be made much more effective if the UX designer sketches preliminary user flows (and even a sitemap or two) ahead of time. Because visualizing how an idea will work is a natural process for visual-thinkers like UX designers, it’s easy to take this for granted. However, it’s supremely important to make sure that any flow(s) being discussed are visualized and shared with the rest of the team.

This is a very collaborative step as every decision can affect the feasibility of the solution. Be open-minded and listen to the rest of your team; they will definitely have great insights on how to make it work. After that point, go back to your desk and document everything that has been decided regarding functionalities and technology that you guys are going to use.

Visual design

When it comes to visual design, simple sketches on paper can greatly expedite the creative process. Not only do they do a great job in terms of saving time, they also feel more collaborative, since changing sketches on paper is easy to do. This helps designers produce an initial look and feel.

When the project is in full swing, partner with Visual Designers to create as many layout variations as possible. This ensures you a better chance of picking the best solution for the interface. Instead of creating wireframes all by yourself, make sure to leave your desk and involve the rest of the team. Afterall, that’s why chameleons have very strong claws: to climb around and find new environments in which they might adapt.

Development

The earlier you partner with developers, the more realistic (budget-wise and time-wise) and innovative your design solutions can become.

Talking to developers is a long process and will bring up discussions that may get very technical and somewhat confusing. Stay with it. Bring a pen and paper (or a whiteboard) to help visualize the concepts with which they’re so familiar.

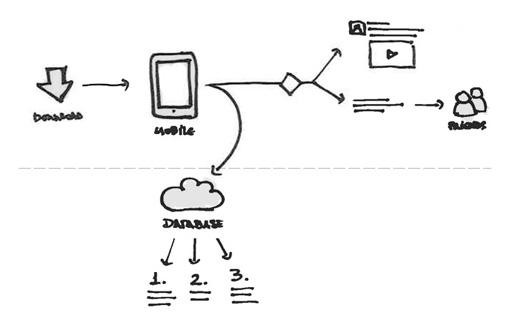

UX deliverable: hybrid of user flow and technical flow

A great deliverable that can come out of these discussions is a mixture of user flow and technical flow, a document that demonstrates everything that happens in the front end (what is visible for the user) as well as the back end (what happens in the backstage). Remember to use your super power of explaining complex things in a simple way.

Measurement

Finally, partner with business intelligence and media analysts to ensure every design works towards strategic, business goals. Meet with these professionals at the beginning of a project in order to determine the designs/flows that will work towards the project’s Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

Next, simply ensure these metrics are addressed at the end of all discussions. Don’t limit things by mentioning them up front, per se, but do ensure KPIs they play a recurring, strategic role.

One skin, many colors

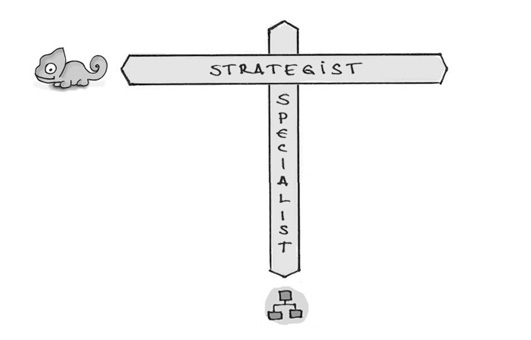

So there you have it. In order to create and develop the partnerships required, designers need to understand a little bit about every discipline. Many people talk about the rise of the T-shaped professional. I prefer the term UX Chameleon.

Chameleons adapt. By their very nature, they merge themselves in with the landscape and become a native in a foreign environment. In a similar way, the best designers bridge the gap between creatives and developers, strategists and producers.

It’s important to note that disguising, in our case, is not a matter of going unnoticed. Such attitude is not helpful neither for the team nor the project. When discussing an interface with a developer, for example, it’s useful for you to understand a little bit of HTML. A common vocabulary with the person you are talking to facilitates a more meaningful conversation. Never forget that design is a process of mutual discovery.

Maybe instead of “UX unicorns” – fanciful creatures that are hard to find and define – we are actually turning ourselves into UX Chameleons: not-so-magical creatures that might be a bit less charming but way more relevant, given our adaptive capabilities.