My initial foray into UX frustrated me. Although my job title suggested that I made products easier for end-users, I actually spent a lot of time selling user experience to clients, stakeholders, and colleagues. I knew I needed to broaden my focus, but I didn’t know where to start. And that’s when I discovered The Business Model Canvas.

The story behind what we today know as the Business Model Canvas is an interesting one. Originally created as a conceptual framework for Alexander Osterwalder’s PhD project, it later became the subject of an entire book called Business Model Generation, co-authored with Yves Pigneur. Today, both the book and the canvas allow those of us without business training (including yours truly) to better understand sustainable business practices.

My application of the Business Model Canvas is likely atypical, though. Instead of using the canvas to aid clients, I wondered: what if I looked at my role as a business itself? After all, I need resources to operate (a budget, my supervisors’ time, my colleagues’ expertise); I have customers (people to whom I provide value); I have costs (my time, materials, stress). Could understanding all these things help me design more efficiently?

Introspection

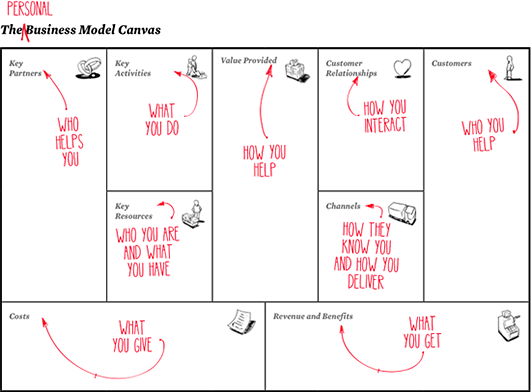

To follow my logic, it’s useful to first understand how the business model canvas is laid out.

Personal Business Model Canvas Worksheet. Source: http://www.businessmodelyou.com

Divided into nine parts, it includes:

- Key partners – Who supports you?

- Key activities – What do you do to create value?

- Key resources – What do you require?

- Customers – For whom do you create value?

- Value – What problems do you solve? What needs do you address?

- Channels – How do you communicate your value?

- Customer relationships – How you interact with customers?

- Revenue – What do you get?

- Costs – What do you give?

Using the original book’s sequel (Business Model You) as a guide, I thought critically about my role within my organization. Rather than rigorously weigh all nine considerations here, though – something for which the book is much better suited – let’s look at three in particular: customers, value provided, and key channels.

Customers: not just the end-user

While it’s relatively easy to assume that our customers are the same as the customers of the company for which we work, this isn’t strictly the case. As the book defines them, customers are anyone for whom we’re creating value, including:

- Clients and stakeholders, who rely on us for our expertise;

- End-users, who rely on us to represent their needs;

- Software developers, who rely on us to clarify interactions and interfaces;

- Other members of the design team, who rely on us for user research; and, finally,

- Colleagues in quality assurance, who rely on us for specifications and clarifications.

Notice that end-users are only one item on the list. Notice, also, that colleagues are customers too. Couple this with the fact that we practice user-centered design and it becomes increasingly obvious why it’s part of our job to consider our team and their benefit.

User experience design isn’t limited to human-computer interaction; it includes human-human interaction as well. Before filling out the canvas, I instinctively knew this – that my responsibility did not end with “end users” – however, I didn’t know what I could do to serve them more effectively. That’s when I considered value propositions.

Value: not just deliverables

Just as clients tend to think of our work as deliverables, designers often think of our work as different activities: holding workshops, conducting interviews, writing scenarios, making wireframes. Yet one of the biggest mistakes we can make is to assume that the activities we conduct are the same thing as the value we provide.

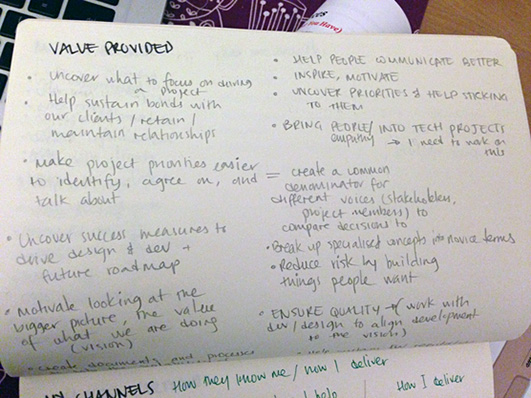

When I sat down to determine the value I provided, I was stumped. I could only think of – dare I say it – clichés. “Making things easy to use,” “generating empathy,” etc. I needed to break it down.

My actual first draft of value provided – this describes what value my role provides, irrespective of activities.

To determine the value I provided to others, I started with a list of what I was currently doing at work: conducting user interviews, diagramming mental models, building low-fidelity prototypes, tracing mind maps, putting together personas. Next, I considered my reasoning for each activity. Why did I interview project stakeholders?, for example.

Then I asked myself: So what? Repeatedly. Until I hit something.

This resulted in the following table:

| Activity | I do this to… | So that… |

|---|---|---|

| User interviews | Build empathy for customers | We avoid building a product “for everyone” |

| Mental Model Diagram | Determine our feature fit | Stakeholders can see gaps |

| Low-fidelity prototype | Share the vision | Everyone can agree to the product direction, sooner |

Does interviewing customers before designing reduce the risk of product-market mismatch? Does one particular kind of prototype make it easier to adapt the design vision? You don’t know until you think it through.

Next, I considered the value provided by each of these activities for my customers:

| Activity | Value to client | Value to developers | Value to designers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Model Diagram | Risk reduction. This helps clients see gaps in their offering (where they might lose competitive edge or profit) | Convenience. This allows developers to more easily write user stories by providing user motivations. | Cost reduction. This provides designers with context so they can more quickly make design decisions. |

Notice how the value differs depending upon the customer. Finding the right way to phrase the value we provide for a given audience is, simply put, a user-centered way of thinking. It requires asking the right questions and actually listening to the answers. In this case, we just have to add business constraints, and organizational fit to our list of topics to listen out for.

Communicating this way signals that we have a wide skill-set. When I sit down at a meeting, I sometimes sense that a new client considers the role of designer to be analogous to that of an aesthetician: the person responsible for adding “color” to an interface. Communicating my role in terms of value signals that I think broadly. It raises expectations.

Key channels: stop waiting for recognition

The third realization I had when filling out the canvas was that I was often waiting for people to become curious about what I did instead of communicating my own value. Channels are the methods we use to communicate to customers. They afford three things:

- Awareness of the value we provide. They allow us to spread the word about what we can offer (and listen to others to see where its needed most).

- The value itself. Channels allow us to deliver the value we promise.

- Customer support after we’ve delivered our value.

Most importantly, this exercise helped me realize that I needed to give more thought to the ways in which I communicated with my customers. To that end, I might:

- Demo something I did in the company demo meeting and talk about the value to developers

- Share a usability test recording

- Make a cheat-sheet of my activities’ benefits for the sales team, or

- Write articles about our process for the company website so clients could learn more about what UX means for business

Making the sale

So there you have it: the business model of a UX Team of One. Selling UX – especially within an organisation – is a complex topic. Whole books have been written on the subject. The three insights above resulted from reconsidering my value and what I could improve on.

I eventually came to realize I needed a plan for communicating value to different groups of people I work with, and that I had to stop waiting and start doing. I also came to accept that there were areas in which I needed help – such as translating my reasoning for UX activities into business terms. I’m currently working on writing out all these benefits, with the help of an experienced consultant.

The business model canvas hasn’t made my job any easier to do, but it has helped me prioritize. Communicating value is a journey. I recommend filling out the canvas for yourself and seeing which boxes are most difficult to fill (yours might differ from my 3 key learnings) or with which you could use some help. I have no doubt you’ll find the result rewarding.