On Tuesday we spoke with information architect and author Abby Covert, about her new book How to Make Sense of Any Mess. Today, we’ll be offering readers an excerpt of the book itself.

About this preview:

The following is a preview of the first chapter of How to Make Sense of Any Mess. Now available in paperback and for kindle via Amazon.

Introduction

Think about everything you have to make sense of each day. Projects, products, services, processes, collections, events, performances, boxes, drawers, closets, rooms, lists, plans, instructions, maps, recipes, directions, relationships, conversations, ideas. And the list goes on.

Having to progress in the face of chaos, confusion, and complexity is something we all have in common.

Information architecture is a set of concepts that can help anyone making anything to make sense of messes caused by misinformation, disinformation, not enough, or too much information.

Whether you are a student, teacher, designer, writer, technologist, analyst, business owner, marketer, director, or executive, this book is for you.

In the time that it takes to fly from New York to Chicago, I will introduce you to the practice of information architecture so you can start to make sense of whatever messes come your way.

“If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.”

—Carl Sagan, Cosmos

Messes are made of information and people.

A mess is any situation where something is confusing or full of difficulty. We all encounter messes.

Here are some of the many messes we deal with in our everyday lives:

- The structure of teams and organizations

- The processes we undertake in working together

- The ways products and services are represented, sold, and delivered to us

- The ways we communicate with each other

It’s hard to shine a light on the messes we face.

It’s hard to be the one to say that something is a mess. Like a little kid standing at the edge of a dark room, we can be paralyzed by fear and not even know how to approach the mess.

These are the moments where confusion, procrastination, self-criticism, and frustration keep us from changing the world.

The first step to taming any mess is to shine a light on it so you can outline its edges and depths.

Once you brighten up your workspace, you can guide yourself through the complex journey of making sense of the mess.

I wrote this simple guidebook to help even the least experienced sensemakers tame the messes made of information (and people!) they’re sure to encounter.

Information architecture is all around you.

Information architecture is the way that we arrange the parts of something to make it understandable.

Here are some examples of information architecture:

- Alphabetical cross-referencing systems used in a dictionary or encyclopedia

- Links in website navigation

- Sections, labels, and names of things on a restaurant menu

- Categories, labels and tasks used in a software program or application

- The signs that direct travelers in an airport

We rely on information architecture to help us make sense of the world around us.

Things may change; the messes stay the same.

We’ve been learning how to architect information since the dawn of thought.

Page numbering, alphabetical order, indexes, lexicons, maps, and diagrams are all examples of information architecture achievements that happened well before the information age.

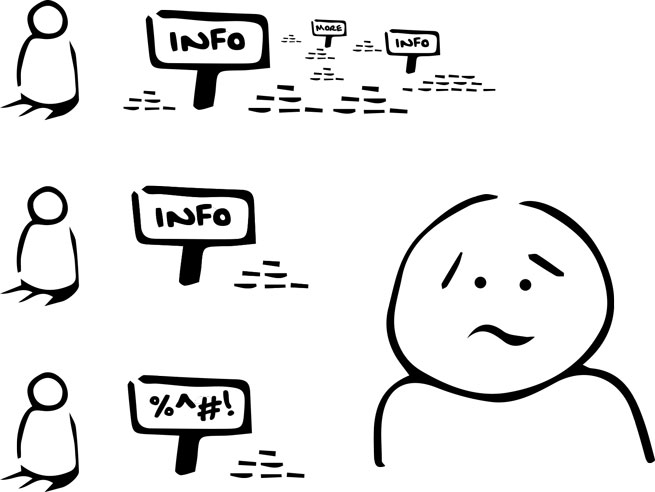

Even now, technology continues to change the things we make and use at a rate we don’t understand yet. But when it really comes down to it, there aren’t that many causes for confusing information.

- Too much information

- Not enough information

- Not the right information

- Some combination of these (eek!)

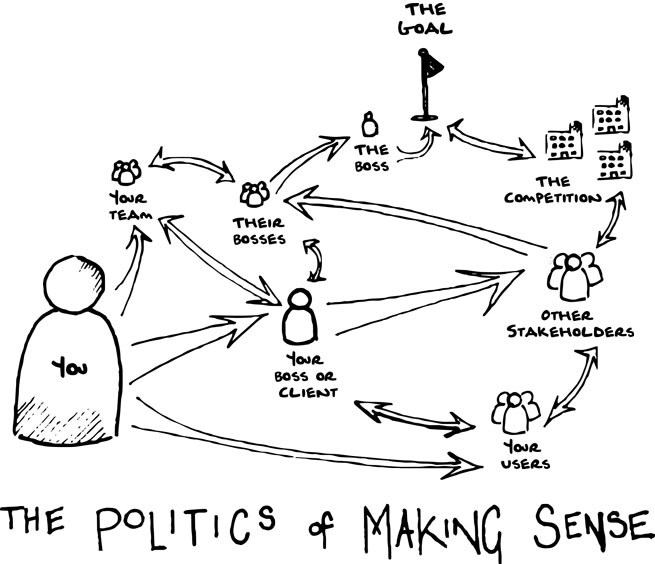

People architect information.

It’s easy to think about information messes as if they’re an alien attack from afar. But they’re not.

We made these messes.

When we architect information, we determine the structures we need to communicate our message.

Everything around you was architected by another person. Whether or not they were aware of what they were doing. Whether or not they did a good job. Whether or not they delegated the task to a computer.

Information is a responsibility we all share.

We’re no longer on the shore watching the information age approach; we’re up to our hips in it.

If we’re going to be successful in this new world, we need to see information as a workable material and learn to architect it in a way that gets us to our goals.

Every thing is complex.

Some things are simple. Some things are complicated. Every single thing in the universe is complex.

Complexity is part of the equation. We don’t get to choose our way out of it.

Here are three complexities you may encounter:

- A common complexity is lacking a clear direction or agreeing on how to approach something you are working on with others.

- It can be complex to create, change, access, and maintain useful connections between people and systems, but these connections make it possible for us to communicate.

- People perceive what’s going on around them in different ways. Differing interpretations can make a mess complex to work through.

Knowledge is complex.

Knowledge is surprisingly subjective.

We knew the earth was flat, until we knew it was not flat. We knew that Pluto was a planet until we knew it was not a planet.

True means without variation, but finding something that doesn’t vary feels impossible.

Instead, to establish the truth, we need to confront messes without the fear of unearthing inconsistencies, questions, and opportunities for improvement. We need to be open to the variations of truth that are bound to exist.

Part of that includes agreeing on what things mean. That’s our subjective truth. And it takes courage to unravel our conflicts and assumptions to determine what’s actually true.

If other people have a different interpretation of what we’re making, the mess can seem even bigger and more hairy. When this happens, we have to proceed with questions and set aside what we think we know.

Every thing has information.

Over your lifetime, you’ll make, use, maintain, consume, deliver, retrieve, receive, give, consider, develop, learn, and forget many things.

This book is a thing. Whatever you’re sitting on while reading is a thing. That thing you were thinking about a second ago? That’s a thing too.

Things come in all sorts, shapes, and sizes.

The things you’re making sense of may be analog or digital; used once or for a lifetime; made by hand or manufactured by machines.

I could have written a book about information architecture for websites or mobile applications or whatever else is trendy. Instead, I decided to focus on ways people could wrangle any mess, regardless of what it’s made of.

That’s because I believe every mess and every thing shares one important non-thing:information.

What’s information?

Information is not a fad. It wasn’t even invented in the information age. As a concept, information is old as language and collaboration is.

The most important thing I can teach you about information is that it isn’t a thing. It’s subjective, not objective. It’s whatever a user interprets from the arrangement or sequence of things they encounter.

For example, imagine you’re looking into a bakery case. There’s one plate overflowing with oatmeal raisin cookies and another plate with a single double-chocolate chip cookie. Would you bet me a cookie that there used to be more double-chocolate chip cookies on that plate? Most people would take me up on this bet. Why? Because everything they already know tells them that there were probably more cookies on that plate.

The belief or non-belief that there were other cookies on that plate is the information each viewer interprets from the way the cookies were arranged. When we rearrange the cookies with the intent to change how people interpret them, we’re architecting information.

While we can arrange things with the intent to communicate certain information, we can’t actually make information. Our users do that for us.

Information is not data or content.

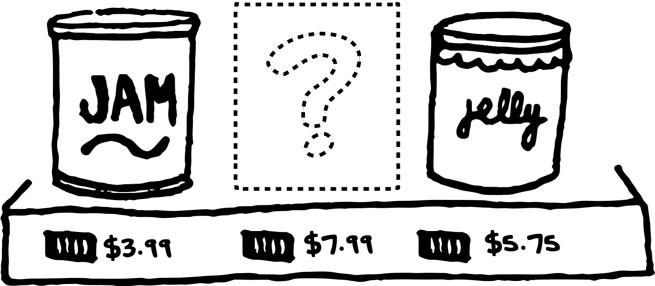

Data is facts, observations, and questions about something. Content can be cookies, words, documents, images, videos, or whatever you’re arranging or sequencing.

The difference between information, data, and content is tricky, but the important point is that the absence of content or data can be just as informing as the presence.

For example, if we ask two people why there is an empty spot on a grocery store shelf, one person might interpret the spot to mean that a product is sold-out, and the other might interpret it as being popular.

The jars, the jam, the price tags, and the shelf are the content. The detailed observations each person makes about these things are data. What each person encountering that shelf believes to be true about the empty spot is the information.

Buy the book to read more.

This brings us to the end of the free preview. Below is the full table of contents so you can get a sense of where things go from here.

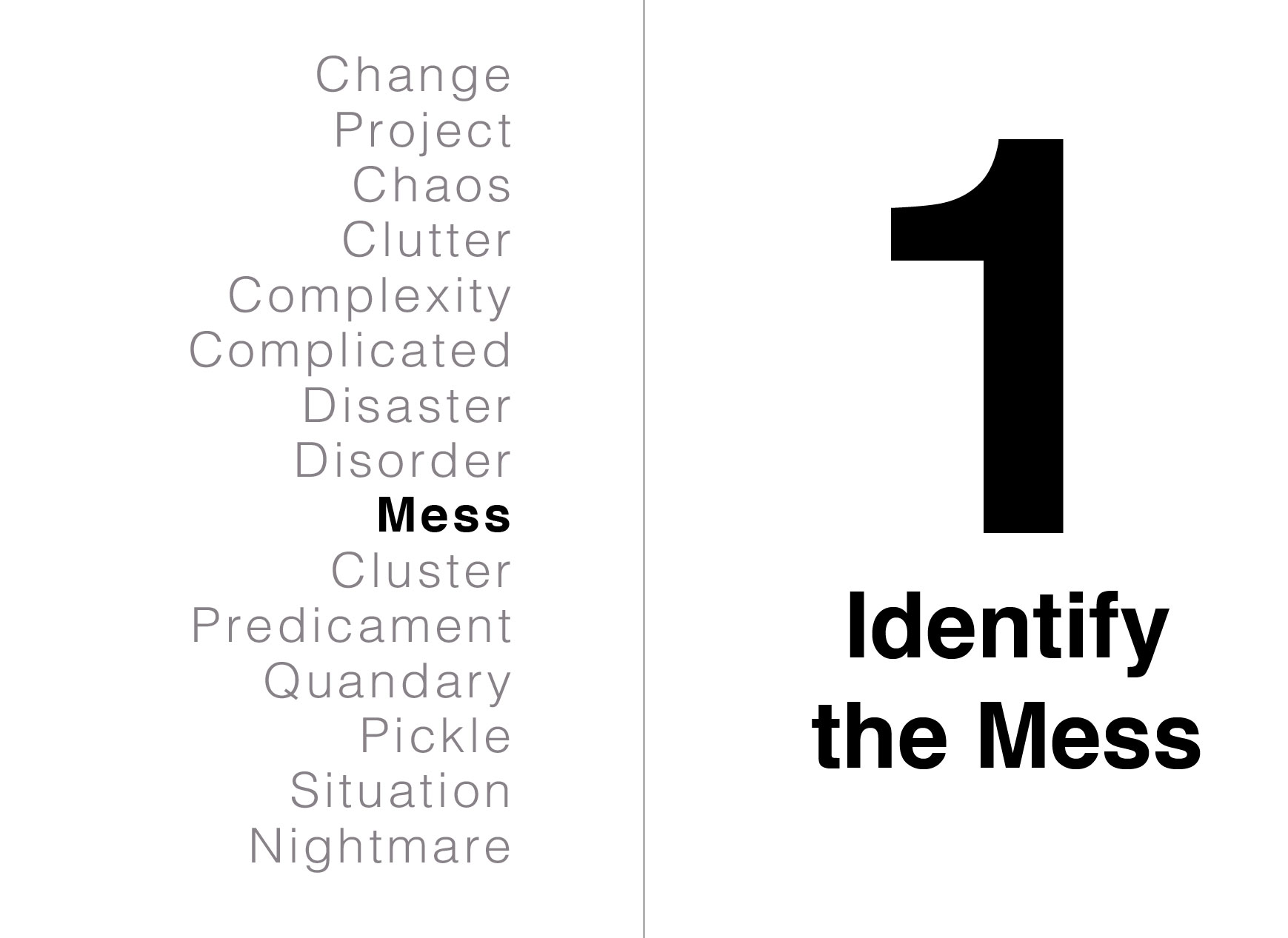

- Identify the Mess

- State Your Intent

- Face Reality

- Choose a Direction

- Measure the Distance

- Play with Structure

- Prepare to Adjust

The lexicon of terms and the story of how this book was created is also available online. More information on the project can be found on the book website.

If you are interested in purchasing the book, it is available in paperback and for Kindle through Amazon.

Copyright 2014 by Abby Covert — All rights reserved.