“To understand the whole of a book it is necessary to grasp its individual words and sentences, but those words and sentences only have meaning within the larger context of the book, hence interpretation must be a matter of constant revision: revising one’s sense of the whole as one grasps the individual parts, and revising one’s sense of the parts as the meaning of the whole emerges.” -Paul Kidder – Professor of Philosophy in Gadamer for Architects

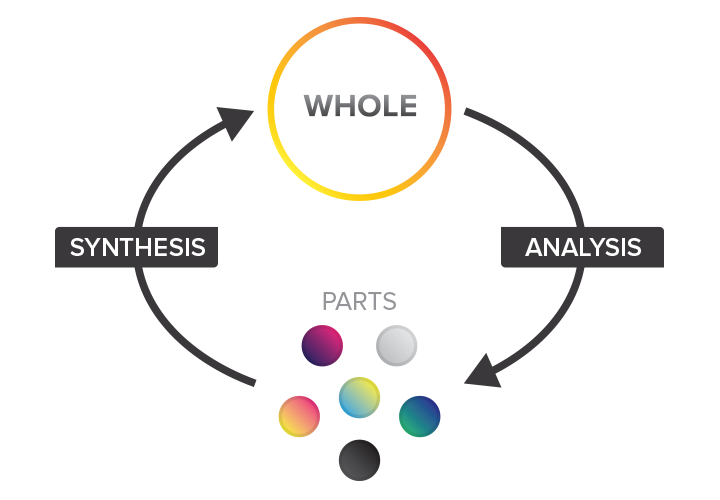

The process Paul Kidder identifies in Gadamer for Architects is known as the “hermeneutic circle.” Central to this process is understanding both the bigger picture in relation to the details and the details in relation to the bigger picture. This understanding grows and changes as we continue to come across additional details, whether the big picture is a UX project or something as simple as reading a book.

In design we are constantly moving along the hermeneutic circle. When we start a project we have all kinds of assumptions about how the work might unfold, but we also know from experience that we’ve often been mistaken in the past, so as with reading the pages of a book, we go through a set of activities that allow us to check our assumptions and grow our understanding.

How might we use hermeneutics to benefit our designs? I will answer this question by first taking a look at the history of the philosophical framework, and then walking through an example of an old text informing new ideas. Finally, I’ll offer some starting points for other UX designers to begin hermeneutical explorations.

The History of Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics is a framework that we can use to think and talk about understanding. It comes from the ancient Greek word for interpretation and as a framework its roots go back to the early days of Western philosophy.

The hermeneutic circle

Hans-Georg Gadamer, born in Germany in 1900, was the philosopher who contributed most to contemporary hermeneutics. Gadamer’s hermeneutics combines three interrelated concepts: the horizon of understanding, prejudices, and conversation as a model for understanding.

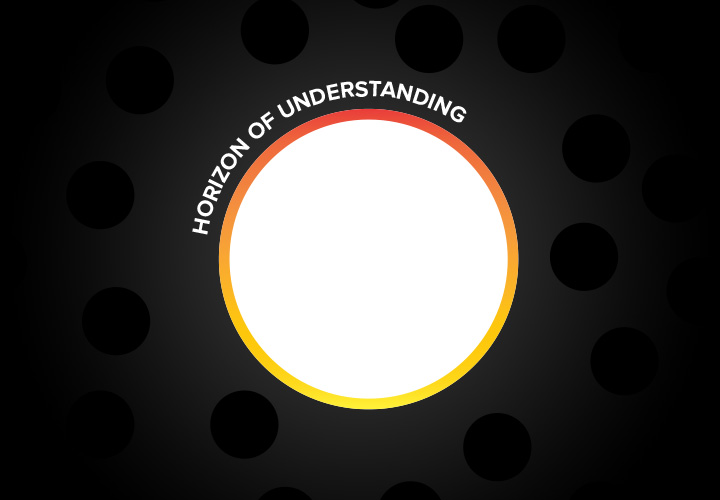

Horizon of understanding

When we try to understand something new, the first thing we have to realize is that we don’t approach the new from some neutral vantage point, but from within our own particular perspective. Gadamer calls this personal understanding our “horizon of understanding.” Our horizon consists of the knowledge we’ve gained from our history, the culture we’ve grown up in, and “all our feelings, sensibilities, habits and associations.” In short, the horizon of understanding contains everything we use to make sense of the world around us.

Our horizon of understanding

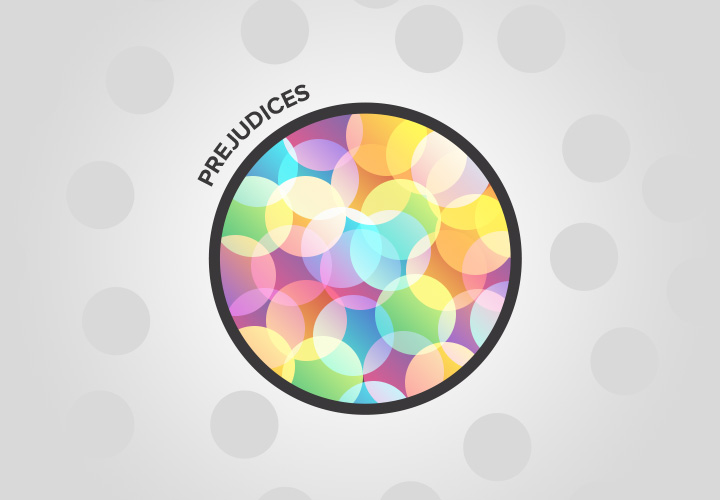

Prejudices

Gadamer calls all the knowledge that makes up our horizon “our prejudices.” For Gadamer, having prejudices is not necessarily negative, but inescapable. Most of the time our prejudices remain hidden to us. However, we can see our prejudices revealed when we’re in a situation that clearly doesn’t align with our expectations. For example, the first time we’re working on a design project that supports more than English as a language, we are forced to expand our horizon and understand that other languages might need a lot more (or fewer) characters to say the same thing, and that if left unaddressed this could completely break our layout.

Our horizon contains all our prejudices

There is no understanding without prejudices, and the idea that you should free yourself from them is a ‘superficial demand.’ All thinking is determined by its horizon, its context.

— Paul Kidder

No matter how much we’d like to start a new project or approach a new person from a blank slate, our past experiences will always frame how we approach the world. This doesn’t mean that we’re doomed to be stuck in the past; our job is to approach the world knowing that we are prejudiced and continuously work on overcoming those prejudices towards better understanding.

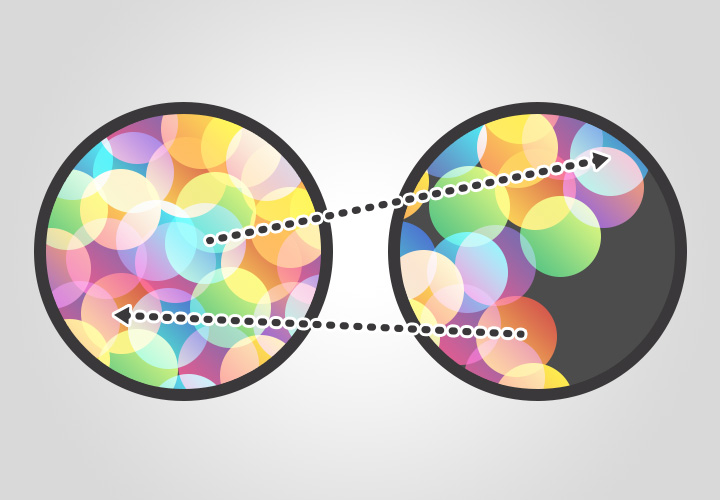

Conversation as a model of understanding

I once worked on a project to update a simple form submission process that required the user to pay a fee. Our initial idea was to let users fill in their credit card details as part of the form, and then press pay to complete the form. After speaking to users, we learned that some people don’t have a debit or credit card, or even a bank account. Our original design would not work: we needed to make the form submission independent from the payment. If we had not checked our assumptions and expanded our horizons, a whole user group would have gone unserved.

a conversation as a model for understanding

How can we overcome our prejudices and expand our horizon? Gadamer explains this through the model of a conversation. In most conversations where we learn something new, we follow a pattern:

- Listen

- Reflect

- Ask questions

- Consider new examples

- Summarize what we hear

Gadamer suggests this as a model for thinking and understanding anything, from an ancient text to an academic paper on interaction design.

We can use the tools of a good conversation in our UX process. To start, a conversation will only work if we begin with the expectation that others (our users, stakeholders, as well as the documents that surround every project) have something valuable to say. Second, we can’t control the conversation if we hope to stay open to new understanding. We need to develop, question, phrase, and rephrase our language. Finally, a successful conversation doesn’t simply transfer information; it expands both parties’ horizons.

Most successful design projects already start with the assumption that we are limited by our own horizon, and thus we need to engage in a series of activities to learn and expand them. Thinking about this in terms of the hermeneutic circle can help us focus on challenging our prejudices.

Applying hermeneutics

The hermeneutical approach opens up the whole of history as a resource for designers. For example we can look at the prescient essay As We May Think, written by Vannevar Bush in 1945. In this essay he sets out an argument for improving scientific research by making past findings more accessible. He imagines the invention of a memex: a device that scientists can use to store all their books, records, and findings, then use to quickly find and re-trace previous work. Bush writes about the futuristic machine he imagines: “One can now picture a future investigator in his laboratory. His hands are free, and he is not anchored. As he moves about and observes, he photographs and comments. Time is automatically recorded to tie the two records together.”

In many places the essay – over 70 years old – sounds strangely familiar. From today’s perspective, we might perceive it as a strange mash up between browser history and a program like Evernote. In fact, in an interview in 2008 Evernote’s CEO Phil Libin confirmed that you could think about Evernote as ‘your personal memex’.

Photo Credit: Derek Mueller via Compfight cc

When creating the user experience for Evernote, a designer could use the hermeneutical approach to better understand personal memory systems and how a design can free up time for mature thought. To this end, Bush’s essay would make a good conversation partner, giving the designer a chance to learn where the ideas of a personal memory system came from and to see if there are ideas that might inspire us, challenge us, and expand our horizon.

In the article Bush gives some insights into why he has come up with this vision for the future: to free up time for mature thought.

For mature thought there is no mechanical substitute. But creative thought and essentially repetitive thought are very different things. For the latter there are, and may be, powerful mechanical aids.

As we would during a normal conversation, first we must assume that Bush has something of value to share, and then we can start to ask questions.

What does he mean by mature thought?

Bush starts by stating that while we’ve been using machines for calculations for a long time, we haven’t mechanized the filing and storing of articles.

Adding a column of figures is a repetitive thought process, and it was long ago properly relegated to the machine. […] The repetitive processes of thought are not confined however, to matters of arithmetic and statistics. In fact, every time one combines and records facts in accordance with established logical processes, the creative aspect of thinking is concerned only with the selection of the data and the process to be employed and the manipulation thereafter is repetitive in nature and hence a fit matter to be relegated to the machine.

Now we can start to form a more complete picture. Were this a conversation, we might respond: “I see, you think we’re spending a lot of time using mechanical thought to keep track of the quotes we want to reference, rather than using creative thought to actually write the essay”

How can we reduce time spent in mechanical thought?

Now that we understand Bush’s distinction between mechanical and creative thought, we can start a new hermeneutic circle, to better understand the challenges facing the automation of thought.

[The problem with retrieving information is] our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing. […] the human mind does not work that way [filing thoughts by alphabetical or numerical categories]. It operates by association.

The solution (he believes) should therefore be found in building technology that follows how humans think.

Man cannot hope fully to duplicate this mental process artificially, but he certainly ought to be able to learn from it. In minor ways he may even improve, for his records have relative permanency. Selection by association, rather than indexing, may yet be mechanized.

When he describes how this selection by association can be mechanized, we see how an Evernote designer could be inspired. A user of Bush’s memex machine “goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own, either linking it into the main trail or joining it by a side trail to a particular item. […] He inserts a page of longhand analysis of his own. Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.”

Bush threads and individual’s own path and associative sense-making as an activity worth focusing on, an idea an Evernote designer can explore during design sessions. By being aware of the horizon of our own thinking and opening up a conversation with texts that shaped our past we can extend our horizons and create a deeper understanding about our world.

Next Steps

In every area of design there are many classic texts and papers to take ideas and inspiration from. A great place to start hermeneutic conversations is the the IxD Library, a website that lists influential books and papers all the way back to Vannevar Bush’s 1945 essay.

- Take part in a design critique and try to make points by only asking questions.

- Read an essay from IxDA library written before 1980 and consider the impact it had on the field.

- Have a look at Bret Victor’s online essay Magic Ink and see how he converses with many older sources and uses this to extend his own horizon and come to better solutions.

Reading any of these essays will begin a hermeneutical investigation that delves into our past, and exposes our prejudices. It may shine a light on prejudices held so close that they’ve become invisible. Once uncovered, we can better understand the ideas and assumptions that form our modern design practice, and reopen routes that were closed in the past.