Cookie notifications: those small boxes asking users to acknowledge that a site has cookies – those data packets that allow people to be identified and tracked. The notifications are widely reviled by designers, and users find them annoying, aggravating, or at best, easy to ignore. But they come from a good place – the very best intentions!

Privacy and cookie notices emerged as a result of the European Union’s privacy directive of 2002. The goal was to let people know that sites might collect their personal information, and therefore give users more control over how their data was tracked and used. It didn’t quite work out that way, though. Companies did the bare minimum to comply with the law, pasting tiny notices on their sites – or larger, uninformative ones – which stated that usage implied consent.

The end result: these well-intentioned laws led to degraded UX, with little additional privacy at the end of the day. In this article, we’ll take a look at the amazing opportunity we as designers have to improve online privacy, thanks to a new regulation in the EU.

Why does digital privacy matter?

Digital privacy is a hot, much discussed topic. I’ve argued that people have a right to freedom and privacy, and that this extends to their right not to be tracked online. Others, such as researcher and author danah boyd, see the Internet as a public space. Here’s a quick summary of my argument:

- Users share sensitive information on the web and their devices, asking search engines the most personal questions about their health, private lives and basically everything else. We as designers have a responsibility to honor that deeply private connection.

- Privacy is in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Just as people have a right to freedom from interference in their homes, where they can draw the curtains, they should have that same freedom online.

- Online privacy affects the lives of people living under dictatorial regimes, and can lead to unjust detention.

- If information about users is shared indiscriminately, it can affect things like access to credit or reasonably priced insurance.

Now, the European Union – a leader in digital privacy laws – is trying to turn the situation around, and actually improve privacy online, with the General Data Protection Regulation, which is the biggest update to privacy laws in about 20 years. Starting in 2018, they’ll require online businesses to (among other things) get informed consent from users to their data collection practices. Sites will be expected to both inform users about their privacy practices in truly intelligible ways, and then gain some sort of pointed consent to those practices.

Technically, only companies that have EU users need worry about these laws. But since the web doesn’t have borders, those distinctions are a bit meaningless. That’s why the privacy protections for EU citizens often end up getting extended to all, and why American, Ghanaian, and Japanese websites may use cookies notices too.

Designing for Informed Consent

Right now, websites are already scrambling to begin designing in anticipation of the new laws at the advice of their lawyers. Privacy is a huge challenge for the legal advisers of companies that will be subject to the coming fines – right now privacy violation fines are capped around $300K-$500K, but in the ramp up to 2018, they will rise to $5M-$10M. The two areas lawyers are advising clients’ work on now are:

- Clearly informing users of how their data will be used

- Getting actual consent to those data practices

Informing

To fulfill the “informing” part of the directive, Jerry Ferguson, a lawyer at Baker Hostetler who is actively advising clients on evolving privacy laws, told me that he advises his clients to adopt a “layered approach” to privacy policies. That’s when the top layer presents the information in the most digestible, user friendly way possible, a middle layer gets a bit more into the weeds, and the bottom layer presents all of the details and minutia of the policy.

Both Channel 4 andThe Guardian provide good examples of this, in the form of easily digestible videos. McAfee offers a comic strip version of the “top,” user friendly privacy info layer. Media formats like comics or videos tend to make it easier and perhaps more enjoyable for users to consume than legal fine print.

Consenting

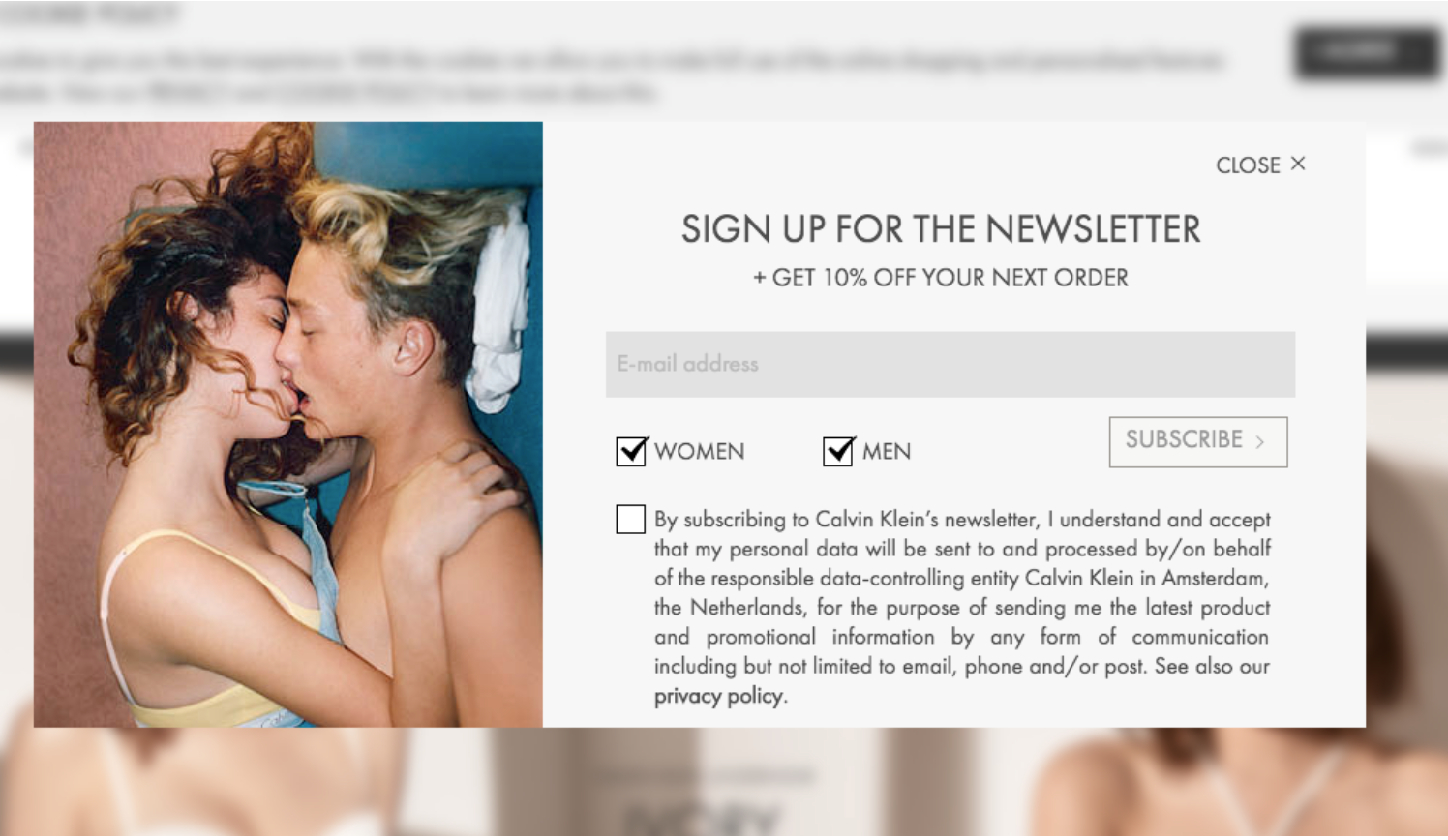

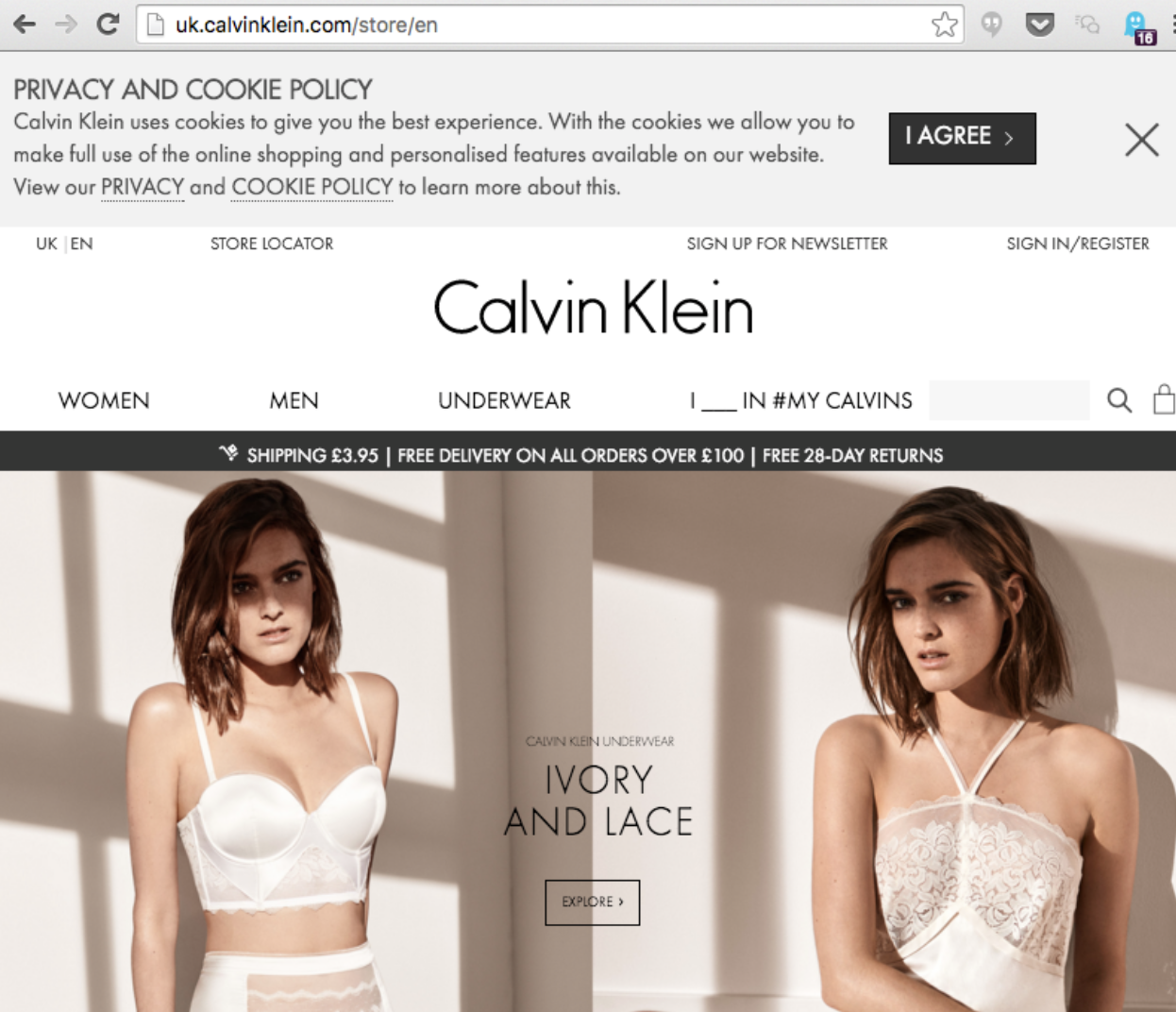

As for getting consent and being more explicit, Calvin Klein’s UK site does a couple of proactive things. In order to subscribe to the site’s newsletter, users must accept the terms of that newsletter – including where user data is stored – first, and those practices are spelled out pretty clearly right next to the check box. In addition, the site’s “I Agree” button clearly asks users to consent. The site’s owners could make a good argument that users click “I agree” with a true understanding of privacy practices.

However, the site’s privacy policy states that simple usage of the site gives tacit approval to Calvin Klein’s privacy practices. Users who do not click “agree” and continue to use the site are still tracked. So while the site is moving in a positive direction, the privacy policy still provides a loophole as a guard against legal fines. Many companies use these sorts of systems to ostensibly comply with laws without actually providing users additional privacy or control.

A better solution would be to give users the ability to disagree – essentially, to opt out of the site’s data practices – and continue using the site without being tracked.

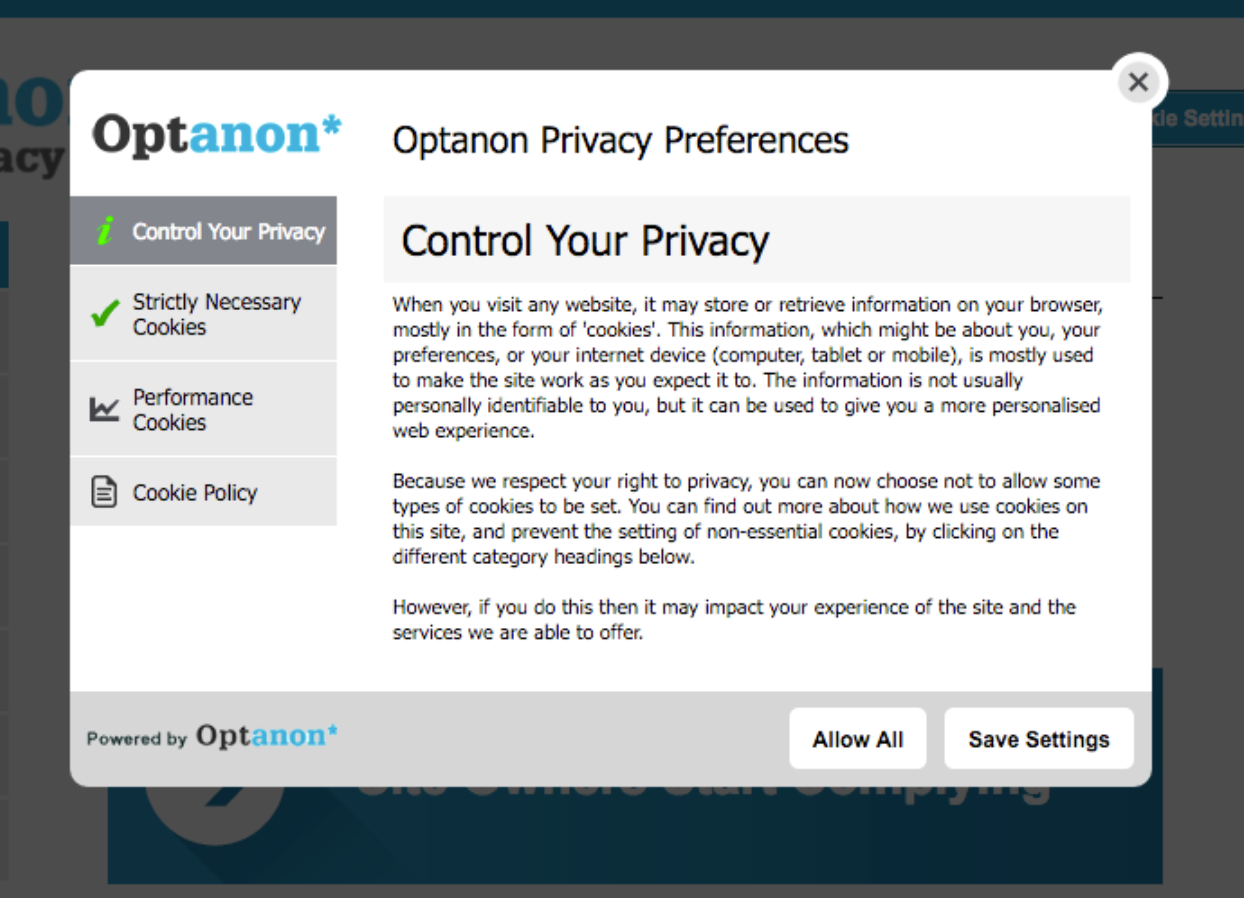

A better option for consent is Optanon, formerly known as The Cookie Collective. Optanon is a third party service that businesses can contract with to make sure they are compliant with EU privacy laws, giving users deep control of the privacy of their data on any site they visit.

There is little debate that once users have set up their privacy preference on this site, that they have consented to and fully understand the practices of that site. Whether users will take the time to set up preferences like this is another matter.

For designers at companies that collect any amount of user data (which is most), designing for informed consent honestly and clearly will be crucial to complying with the coming laws. But while those UX challenges will need to be confronted, there’s a much bigger problem to seeking informed consent for privacy practices online: analysis paralysis.

The real big problem

Getting “informed consent” from users every time they visit a website is not a solution that scales. And yet, informed consent is going to become more and more important as we move toward a future where not only our computers but everyday objects (via the Internet of Things) begin collecting data about us. The problem is analysis paralysis: too much technical information can be paralyzing to users, rather than liberating. Just think of the fine print in credit card applications. It’s a disclosure, but it is also far too much jargon for the average consumer to understand. As a result, it’s not useful information.

Multiply the fine print in a credit card application to every site on the internet, and we begin to see how informed consent to privacy policies are currently rolling out. The idea that users are expected to read privacy policies – and now, in addition, give consent – on every site they visit is just as absurd as the idea of informed consent is attractive.

Lorrie Cranor, professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon, and her student Aleecia M. McDonald researched the amount of time users would actually need to spend on privacy policies, if they read them all. In total, it came out to 6 weeks per year spent on nothing but reading privacy policies.

Clearly, the idea that users will go from site to site, comprehend a privacy policy and give consent is silly. It’s too much information, and too awful of an experience. After all, no one goes to a site to read a privacy policy. Providing the information in more intelligible ways, as sites are starting to do, is a step in the right direction – but it’s not enough.

What Else Can Be Done?

Just because we can’t force every user to read privacy policies doesn’t mean there’s no solution. In fact, there are several.

Collect data responsibly

Some companies have been scared to put intelligible kinds of notices in the user’s eyeline in part because the businesses collect so much data, and so indiscriminately, that their collection practices are difficult to explain. One simple answer to this, and the resulting burden on users, is to collect no user data at all – though, for most online entities, that’s just not going to happen.

That said, companies could at least stop collecting user data indiscriminately in the hopes that it will yield some nugget of insight, and make more mindful decisions about what they collect. That would make disclosures more comprehensible – and the logic for data collection would be ostensibly more reasonable.

Automate and standardize

But that still doesn’t get around the disclosures and consent. To learn more, I interviewed experts like Cranor and Michelle Dennedy, Chief Privacy Officer at Cisco, who believe we need to be thinking much bigger to solve these problems, automating and standardizing both disclosure and consent. Dennedy envisions privacy “personas” with saved preferences that would kick in depending on whether she was in “work persona” (more secure, access to private servers) or “mom persona” (more open to posting on community forums and using social media).

Cranor is working on a personal “privacy assistant,” which would understand a user’s privacy preferences and give consent automatically as the user went about life. She’s aware that consent is going to become even more complex when the Internet of Things gets in gear. Many products that we interact with in that future won’t even have interfaces on which to read a policy or provide consent! Cranor is also working on privacy “nutrition labels” that would explain privacy policies in a standardized way that anyone could understand, if they cared to. While most people likely would not read them, they would be there for those concerned, and watchdogs could use them to zero in on the worst offenders.

One way or another, these experts believe a set of standards will need to be adopted across the Internet when it comes to explaining the subtleties of privacy and user data. And a massive revolution in consumer understanding would need to occur for users to care and interact meaningfully with such standards. (The average person setting up a privacy assistant seems a bit far fetched in the current climate.) It’s a big shift to imagine. But it could happen, and there are steps we can take to nudge things in that direction.

A Shared Responsibility

It’s clear that the onus shouldn’t be only on users to read, comprehend and consent to arcane privacy practices on every site they visit, removing liability from companies that have “ticked the box” of disclosure. But that doesn’t mean users are off the hook, either. Many groups have a role to play:

- Individuals can take ownership. I also spoke with Dave Wonnacott, Senior Data Developer and Data Protection Officer at The Real Adventure, an agency in the UK. He says, “I don’t think it’s unfair to ask people to look out for themselves… We should encourage individuals to take ownership of their data in a way that means something to them.”

- Government could play a role in enlightening users about personal data and privacy. Cranor suggests that digital data privacy be taught in schools someday. And few strides will be made without legislation prompting businesses to curtail, be mindful and disclose.

- Industry organizations can participate. A few years back, several online advertising groups including the IAB and NAI joined forces to begin implementing AdChoice across the Internet, to give users control of what information advertisers could see about them. While studies have shown that most users don’t comprehend the benefits and rarely click on the AdChoices button, it’s the sort of effort that could work if executed well.

- When it comes to execution, that’s where we designers come in: we can create clear and honest messages, design automated systems, and help it all make sense to users.

Between good design, smart laws and education, common standards adopted by industry groups and companies, and the educated user base that will emerge as a result, this thicket of intersecting issues may all start to make more sense – and become more user friendly – in years to come.