Five years ago, I advocated for ISO standards relevant to UXers and if you haven’t read that article then the short version is that as UX designers, researchers, and strategists we can improve the quality and credibility of our work, if we are familiar with and leverage international standards, just like all other fields of work.

Fast forward to today and we find ourselves a window of opportunity with the new update of ISO 9241-110 which is a fairly short document and arguably the simplest standard to understand and start using in the UX field. So if there’s ever been a time in the last five years to actually get started with ISO standards, then now is definitely the time while it’s hot off the press.

What are International Standards?

So as a quick reminder, international standards are drafted by committees of experts, who each represent relevant organizations and their standards are shared with the public for feedback and improvement. They are then published as objective standards, so they are very much by the people for the people. These standards are then usually adopted by the different national standards bodies around the world.

We use international standards all the time, when we buy food, plug in a toaster, or fill a car with petrol. All these experiences are based on systems and products adhering to standards to ensure safety, consistency, accessibility, and ease of use. Imagine if there were no standard for food production quality or electrical safety!

ISO 9241 is a collection of over 40 individual standards applicable to UX designers because they deal with humans interacting with interactive systems. Different parts of ISO 9241 update at different times and there’s a lot to take in if you’re just getting started, so in this article, we will just focus on that single document that has been updated and now being adopted by the standards bodies in each country.

ISO 9241-110:2020

The formal title of the standard is ISO 9241-110:2020 Ergonomics of Human System Interaction – Interaction Principles and was put together by a committee called PH9 , which comprises representatives from the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors, UK Usability Professionals Association and many others.

In a nutshell, the standard is a 65-point checklist of recommendations to evaluate an interactive system against, including websites and apps. Perfect for an expert usability review. Consider it a more detailed and formalized alternative to Jakob Nielsen’s heuristics (the standard actually references Nielsen as well as Bruce “Tog” Tognazzini).

Each of the 65 points is explained with notes and examples which (rightly so) aren’t limited to web interfaces because this standard and the principles apply to any interactive systems. So don’t be surprised when you read about physical systems like ticket machines and elevators! In this new update which replaces the 2006 standard, they have changed the name from “Dialogue principles” to “Interaction principles”. Lots of the points have changed or been updated but it’s not completely different from the old version, so if you’re familiar with that one you’ll still recognize the new one.

So Let’s Talk About Those 65 Points

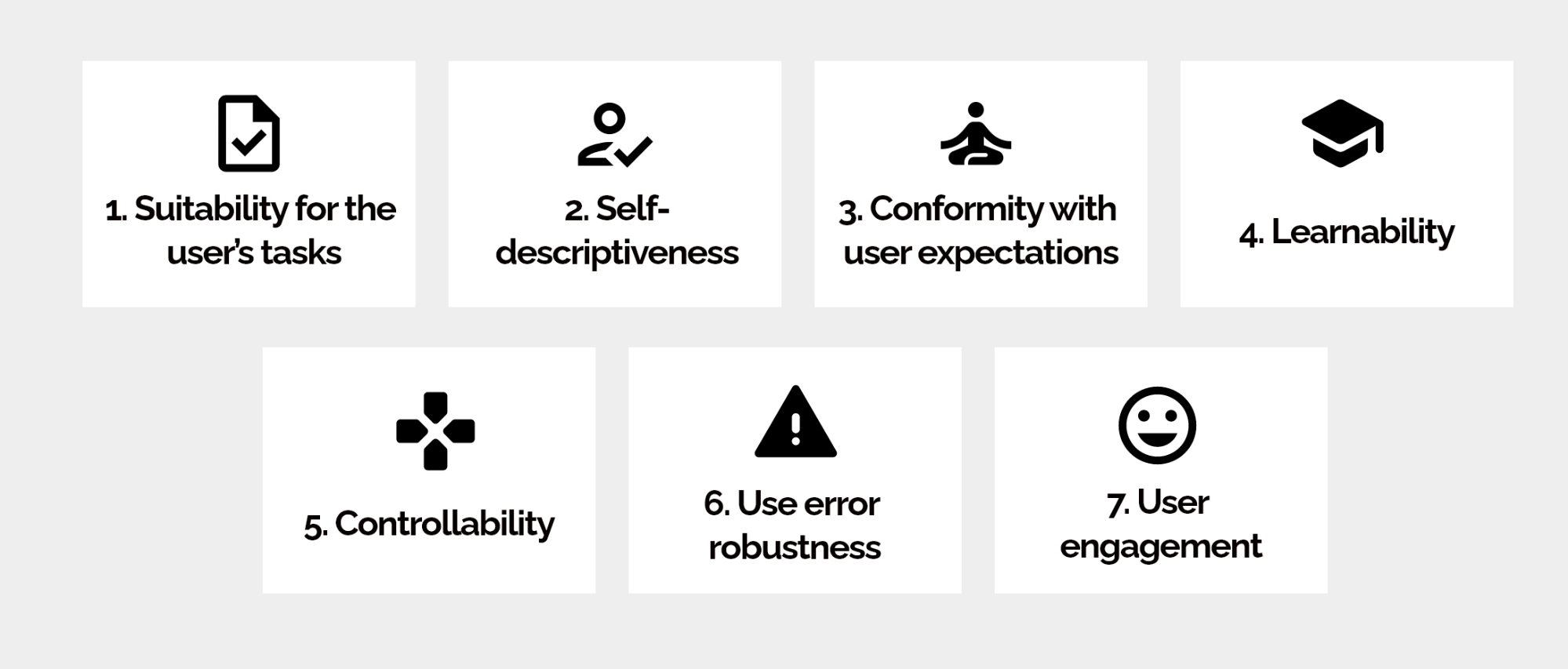

The 65 points aren’t just laid out in one big list, they are split out into sections and start out as 7 broad principles:

These 7 principles are at a similar level to Jakob Nielsen’s heuristics. They are general and broad but a good start nonetheless. Each one is defined, for example, learnability is defined as:

The interactive system supports the discovery of its capabilities and how to use them, allows exploration of the interactive system, minimizes the need for learning, and provides support when learning is needed

Those 7 principles are then split into sets of recommendations. This is where we start to see greater detail, such as in the final principle of “Use error robustness”. The sections are:

- Recommendations related to use error avoidance

- Recommendations related to use error tolerance

- Recommendations related to use error recovery

So we are into greater detail already but those sections are then split into the 65 points. Those points cover a range of things such as first impressions, aesthetics, accessibility, responsiveness and even include some relating to dark patterns such as 5.1.4.2 which says “Avoid defaults, where they can mislead the user”.

Some other examples to give you a flavor are:

- Indicate the progress in the completion of the task

- Present information in a way that clearly indicates which user interface elements are interactive and which user interface elements are non-interactive

- Present information in a vocabulary that is familiar to the user

As you can see this is pretty standard stuff (pun definitely intended) but be aware that this does not aim to be all things in all places. For example, accessibility is a recommendation but does not attempt to replace WCAG, it merely states that the system should be available to the widest range of users. This allows room for additional tests on the same website in terms of accessibility etc.

Why Isn’t Everyone Using this Already?

Good question. From my experience, the two main barriers to using it are:

That really is it. I’m sure many people would still rather not use it even when they have read it but that’s not my experience so far. If you can get over these two hurdles, I’m pretty sure you will become a fan or at least find ways to use it in your work.

By reading this article you have already overcome barrier one, so you only have one barrier remaining. You’re halfway there! Nothing would please me more than to just list out all 65 recommendations here but this barrier really does need to be overcome outside of this article.

Some standards bodies will let you rent the document for a small fee but if you want to keep it, it’s usually priced at around $100 at which point you may rightly ask why make the effort? Why use the standard at all?

I tend to think that question is the wrong way round. Why not use the standard? This isn’t simply shifting the burden of proof because surely an international standard by definition should be the default unless there is a reason not to use it, rather than the other way around.

There is of course an argument to be made for not using it, but if I were looking for an evaluation of my interactive system I would certainly want to know why a prospective supplier wouldn’t use the international standard if they proposed to use anything else. Isn’t that what anyone else would do in other fields of work?

OK, I’m Convinced, Where Do I Start?

So if you are ready to jump on board, here are 5 simple steps to get started with using ISO 9241-110 in a typical usability review:

- Download a copy. You can get it from the ISO website, or your country’s national standards body such as the British standards site or ANSI in the United States

- Read it! It’s only 44 pages long but if you want to cut to the chase then page 21 is where the list of 65 recommendations starts.

- Prepare your checklist. The document has an example table at the end to show how you can keep track during an evaluation.

- Evaluate which points are relevant to the test. Some things may not be relevant so they can be marked as nonapplicable.

- Document each success or failure (and for bonus points offer recommendations on each failed point).

And that’s how simple it is to get started. Once you’ve used it a few times you may find you want to add some criteria or tailor it to the system you are testing or building. The point is that you are using the standard and using the right base to begin with.

Conclusion

So in summary, we have a new window of opportunity with the update of ISO 9241-110. But not only that, but we also have the opportunity to create a shared benchmark. Think of the power of this. Imagine if UX designers all used the same 65 points from an international standard to evaluate websites. Imagine the possibilities! What we have already in WCAG we can also have with ISO 9241-110.