Improving the Conversational Experience

There are plenty of unpleasant experiences I can think of when interacting with nonhuman things. One of the reasons I love Warby Parker is that they still have a human answer the phone instead of a voice assistant. That’s right! No repeating ‘speak to a representative’ and listening to prompts to get your call routed. Sure it’s convenient to ask Alexa to play your favorite song — and if you annunciate it just right, she actually plays it. If you don’t annunciate it just right, no big deal. Interrupt her as she’s reciting the weather by shouting “Alexa!”. Like a genie in a bottle, she’ll light up indigo, indicating she is ready for her command. With a little trial and error, your favorite tune is playing.

The bar is set very low for conversational technology, but it is still gaining popularity. So how do we make it better? The thought of interacting with a conversational device can be dreadful. Authors Diana Deibel and Rebecca Evanhoe teamed up to do their part to change that narrative. The book, Conversations With Things: UX Design for Chat and Voice is “a love letter for conversation designers, new and established”.

Why Conversational Technology?

Diana Deibel and Rebecca Evanhoe met in the VUI Designers community Slack channel. Evanhoe asked if anyone out there “knew how to make voice experiences more accessible?” Deibel co-founded the channel and recently attended a talk on the topic and responded. The two later met in person at an industry conference and connected to write Conversations With Things.

That was in 2018. Since then, conversational technology has gained even more popularity. Almost every website includes a chatbot waving in the corner. Humans are wearing smartwatches similar to this Fossil watch women silver instead of their timepieces. Stereo systems have been replaced with smart speakers. You can select a Netflix movie by talking to your remote control. If you own a Tesla and the vehicle is in park, your passengers can tell your car which “car-aoke” song they want to sing. Within seconds, the tune is playing, the words are queued up on the screen and your passengers are belting their favorite tunes.

Yet the industry’s approach is still technology-centered and not human-centered. Why is that? Shouldn’t everyone just learn how to interact with their conversational device the way it’s designed? Wouldn’t that be easier?

Wrong. These thoughts lingered in the back of my mind the entire time I was reading the book. Luckily, I had the opportunity to speak with Deibel and Evanhoe. “Nothing replaces actually hearing someone getting frustrated,” says Deibel, “listening is the easiest and most accurate way to improve the experience but not the ONLY way to improve it.” Deibel comes from an impressive TV documentary background. “You would never go to production for a TV show without doing a table read first, would you?” I asked her. We laughed, knowing all too well how stakeholders often leave no time or budget for research or testing. That shortsightedness costs you in the long run.

People expect conversational technology to work in the same way they have a conversation with someone. Diana adds a story about her 5-year-old son using a smart remote. “There’s a scene in the movie Cars he watches over and over again. He asked the remote to play that specific scene and quickly learned it did not work.” How adorable, picturing a 5-year-old asking the remote to play his favorite clip. “But why shouldn’t it work that way?” says Diana.

Conversational technology “is a long way from reaching its full potential, in part because people don’t know how to design for interactions where language is the primary way of exchanging information. A lot is being left out. And the only way for the “eld to advance past its current state is to start to get things right.” This book is a great resource to help you do just that.

The book was written to help guide teams through the design process and launch a successful product. There is an emphasis on designing ethically and inclusively throughout the book. “Conversation design is not linear…ethical and inclusive considerations are infused in the daily work of conversational design, ” says Evanhoe in the Rosenfeld Media podcast. Deibal adds, “you can’t just tack it on at the end and hope it goes well.”

Designing a bot is overwhelming. The book warns that teams forget to explore what could go wrong or be dangerous about a product. “Did you hear about the medical advice chatbot that told a patient to kill themselves? Or the Microsoft bot that ingested Reddit content for a day and turned into a distilled racism machine? Or how about when someone threatens to rape a voice assistant, and the assistant ‘res back a joke?” These situations all happened but weren’t anticipated.

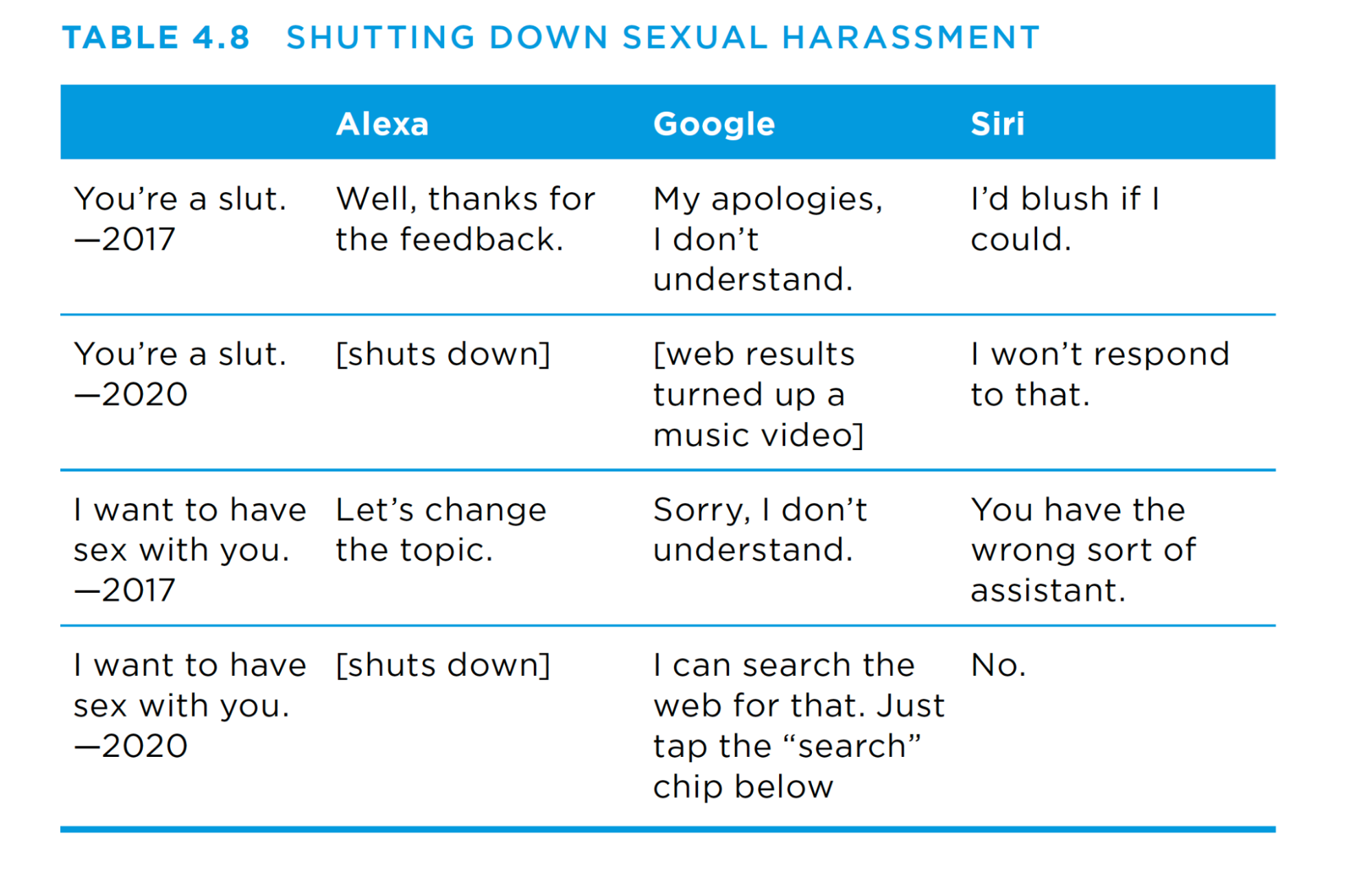

If you look historically at the popular products that made virtual assistance mainstream, Alexa, Google, and Siri, none of those teams considered a human would sexually harass a bot (see Table 4.8). How should something that’s not a human respond to someone saying “I want to rape you”? “It’s a well-studied and reported phenomenon: people sexually harass voice assistants and chatbots, particularly when they’re female-presenting.”

Voice assistants tend to default to a female voice and have feminine names. Sure you can change the voice of your virtual assistant, but take Alexa for example. Why was the decision made to give it a feminine name and voice? Did anyone consider a bot would be a target of abuse? Humans swear and insult voice assistants in a way they wouldn’t speak to a human being. Partially out of frustration. But do we care? Does it harm anyone? Evanhoe says, “Alexa is not a person, it’s 0’s and 1’s at the core of it. So it’s really a matter of studying what are the effects on people? Is there some social good over having a virtual assistant that you get to yell at? Potentially…”

Should You Read the Book?

The book states, “even if you just think about them [conversational interfaces]” you should read this book. If you’re not specifically designing conversational interfaces, you can learn a great deal about how experts are approaching and solving problems. You never know when chatbot or voice assistant requirements will come your way— and you can almost guarantee it will come your way.

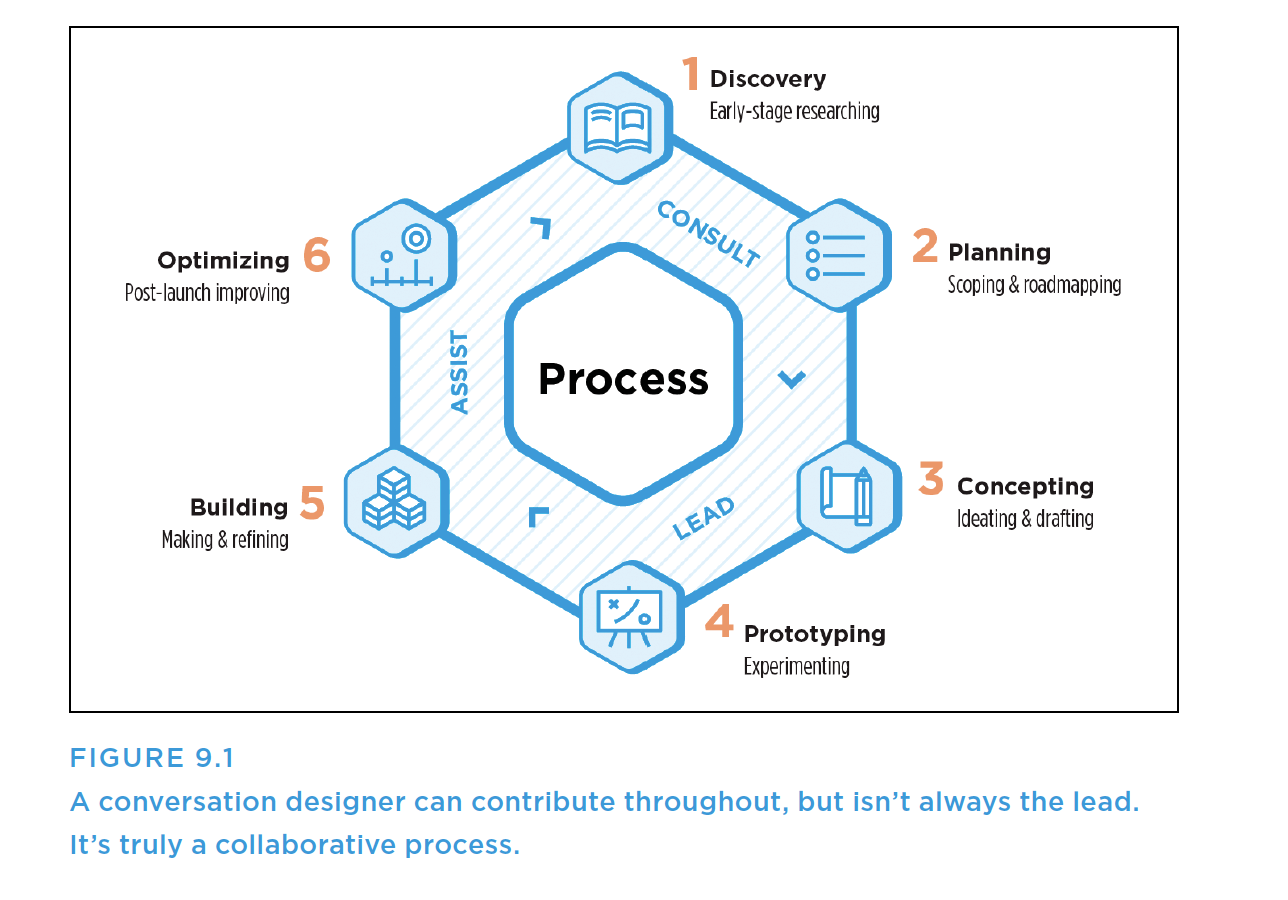

The book reinforces product design processes that are useful no matter what type of technology you are designing. It’s a fantastic blueprint of a process all too familiar but sometimes overlooked —research, prototype, launch, and post-launch improvements are beautifully outlined with real-world examples, failures, and takeaways. Whether you’re leading a team of designers or freelancing, you can implement these strategies in your day-to-day. If you’re new to VUX/VUI design and aren’t sure where to start, Evanhoe was kind enough to provide me with a list of her favorite supplemental tools: Voiceflow, Botmock, Botsociety, Fabble, Voxable. Diana included an invitation link to the VUI Designers community Slack channel, where you can collaborate with other professionals in the field.

The book does a great job cautioning the readers on process as well, “having a process doesn’t melt away uncertainty or guarantee that you’ll get it right, marching ever forward. Figure 9.2 below sums up why you should take our process as a jumping-off point, not a template.”

One of the things I really loved about the book is it encourages designers to “question the idea of an edge case’’ and what steps you can take to design inclusively. “When something is written off as an edge case, that’s a siren for you to start investigating…the people who engage in these so-called edge cases are in marginalized groups—disabled people, people in nonwhite racial groups, and so on.” Oftentimes, it’s folks in marginalized groups who need conversational technology the most and can experience a better quality of life as a result of well-designed products.

A Bright Outlook on the Conversation

Deibel and Evanhoe believe that the future for conversational technology is bright, “people are starting to look at the experience side of things, not just speech recognition” says Deibel. I think you will find this is no easy task and I give these two pioneers a lot of credit for putting this book together. There are many layers to designing something to talk like a person, make it trustworthy, avoid biases, be inclusive and accessible, decide what personality it should have, think about what could go wrong, then deliver a product that gets all of those things right.

Hear More from the Book Authors

The conversation continues! In this podcast, the authors Diana Deibel & Rebecca Evanhoe chat with Lou Rosenfeld about writing the book, the ethics of voice design, and more.

Further Reading

Diana recommends:

Why does Siri sound white? by Amber Nechole Hart

We Should Get Together by Kat Vellos

Becca recommends:

Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need by Sasha Costanza-Chock

Ready to get real about your website's content? In this article, we'll take a look at Content Strategy; that amalgamation of strategic thinking, digital publishing, information architecture and editorial process. Readers will learn where and when to apply strategy, and how to start asking a lot of important questions.