On August 7, 2014, UX designers and developers around the world cheered to the news that Microsoft would officially drop support for older versions of Internet Explorer, effective January 2016. Yet by and large, the outcry was less “hooray for Microsoft!” and more “why didn’t they do this sooner?” The answer is “because people still use IE,” and yet people still use IE because it’s supported, and it’s supported because people use it. It’s a vicious cycle.

Two years ago, Nicholas Zakas wrote an article for Smashing Magazine entitled “It’s Time to Stop Blaming Internet Explorer,” in which he said:

It’s not actually old browsers that are holding back the web, it’s old ways of thinking about the Web that are holding back the Web.

He went on to explain that constraints will always exist, be they older browsers, business requirements, or user needs, and it’s the UX designer’s job to focus on what can be done rather than how to rid the world of the constraint. It’s an intriguing idea. We do work within constraints on every project, and many of them will never wane no matter how much we complain about them, but some constraints can be cracked, or at least altered, if we know where to begin.

We’re often told to ask for serenity to accept the things we cannot change, courage (or coffee) to change the things we can, and the wisdom to know the difference. By understanding where constraints originate and why users react to a given constraint the way they do, we can gain the wisdom we need to identify whether each constraint should be accepted, or challenged.

The MAYA principle

Older browsers aren’t the only constraint subject to a vicious cycle. The same is true of any constraint that users are familiar with – users, after all, prefer “the devil they know.” Think, for example, of the best practice “keep the interface simple,” and how often it is broken because usability testing shows the site’s users don’t think to visit a second page, click on a “see more” link, or hover over a dropdown navigation.

As UX designers, we’re (generally speaking) technologically savvy with access to the latest design fads and sleekest interfaces. However, websites created for “everyone” must include the large portion of the population without our technological prowess – which means sometimes breaking with our sleek, hip best practices. It’s in creating for “everyone” that we settle into the cycle of “the users wouldn’t recognize anything else, so we can’t give them something new.”

The way to break out of this cycle is summarized by the industrial designer Raymond Lowey’s “MAYA principle.” The MAYA principle states that designers are responsible for creating the most advanced creations they can, without creating interactions or interfaces that users will be unable to understand. In this way, they can push the envelope bit by bit, gradually breaking out of old cycles and teaching users to recognize new concepts, be they a “swipe” as a method of scrolling or a phone as an acceptable camera-and-iPod replacement.

There are tools that can help users to progress to more advanced, yet still acceptable, ideas. For example:

- Progressive reduction: providing beginners with additional content to help familiarize them with a new application. Essentially, this works as an in-context help manual.

- Gradual rollouts: to upgrade an existing tool, follow Google’s plan for integrating Hangouts into Gmail. Rather than updating everyone at once, they are slowly rolling out the tool, allowing users to revert back to “classic chat” for over two years – though we’re approaching the mandatory update!

- Skeuomorph for familiarity: when creating a new product, utilize familiar models to help users feel comfortable. Kindle, for example, has done a great job of maintaining a familiar “book” interface to help users with the transition away from paperbacks.

Any of these suggestions will help to move users away from potential constraints, but before we do that, we need to identify whether the constraint is, in fact, one to accept or challenge.

Identifying constraints

Much has been written on constraints’ ability to provide shape to creativity. Constraints can add inspiration, and enforce the need for simplicity. But constraints are like walls; some walls are helpful because they keep us from wandering too far astray. On the other hand, if walls are all around us, they merely box us in.

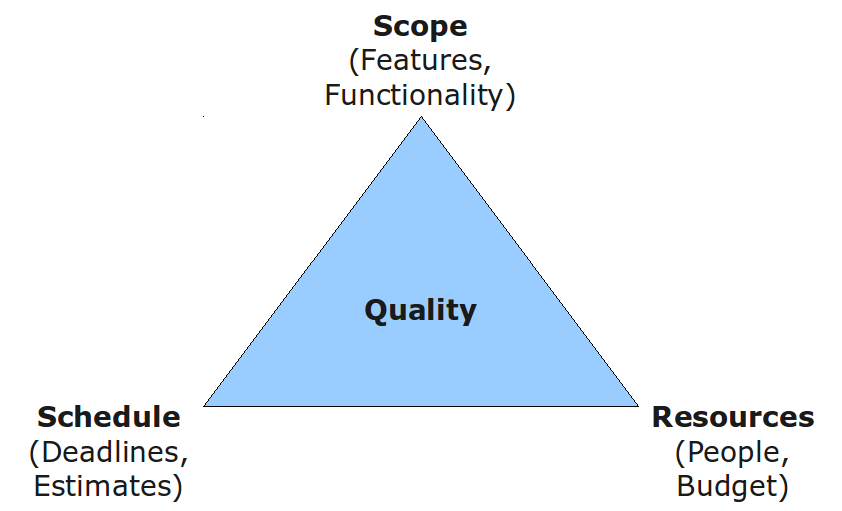

Scope, schedule, and resources are often acknowledged as the three primary constraints we come up against – the “Iron Triangle” of constraints, where each impacts the other two. If the scope is constrained, the project may become easier, as long as the schedule and resources are not also severely constrained. These three constraints are typically constraints that act as helpful walls, guiding us on our way.

On the other hand, some constraints act as barriers. Common barriers include extremely limited budget, limited access to users or user research, clients who want a product without holistic thinking, a lack of development capabilities, or (of course) a user need that conflicts with a best practice – such as end users on IE 6.

The Indigo Studio Blog classifies a good constraint as “one that enables a designer to discover and realize a great design.” Barriers, however, do not enable designers; they block them from being able to help users, either because of a poor browser experience or because a business requirement has become a constraint that contradicts the user’s need. In the case of the latter, the constraint is unnecessary – and the key is the contradiction.

Identifying a constraint as good or bad is not the same as identifying whether it can be challenged. Unfortunately, some barriers exist for a reason. Just consider the struggles that educational apps face when attempting to create social areas for their users. Due to COPPA, a valuable law aimed at protecting children from privacy issues on the web, classroom teachers cannot sign students up for any website or application without parental approval, which can be difficult to obtain in homes with busy parents or neglected children (who are often those that would most benefit from educational sites). The constraints that COPPA inflicts are necessary, but they are not inspirational constraints. On the other hand, many organizations struggle with the constraint of users using older browsers. Some choose to develop for older browsers. Others simply redirect users on older browsers to pages recommending they upgrade.

To identify whether a constraint is permanent, consider these three questions:

- Do I have the power to change this today?

- Do I know who to ask, to change this in the next few weeks or months?

- Are there steps I can take to change this gradually, over time?

-

If the constraint comes in the form of business requirements contradicting user needs, a UX designer will likely know who to address and how to remove the barrier. However, if the constraint is due to browser choice, it will take more than stakeholders’ permission to change.

Impacting change

When it comes to cultural constraints – i.e. what users are familiar with – we are faced with the age-old philosophical question: what is our role as UX designers? Are we responsible for providing clients with what they want or with what will usher in the future of the web? The answer (also age-old) is both. We are responsible for finding the solution that achieves the MAYA principle and gradually moves users toward the future as we see it unfolding. That’s what it means to be specialists in a field that impacts nearly every human being on the planet.

Thankfully, the end is near for the many constraints that come from IE 6 and 7, but not because Microsoft awoke one morning and decided to stop supporting older browsers. Their decision was likely based on data – such as the knowledge that IE users have dropped from 22% to 8% over the last three years. Users are dropping because of Chrome and Firefox’s marketing, to some extent, but also because of the work UX designers have done to help migrate older or less informed users to better experiences.

It is not our responsibility to remove every constraint. It is, however, our responsibility to separate the useful constraints from the barriers, and continue the gradual fight against seemingly permanent walls.