Cooper, co—founded by industry giant Alan Cooper and his wife Sue, is a leading user experience and service design consultancy based in San Francisco. The company helps businesses uncover product, service and business opportunities and offers training in topics such as product and service design, brand strategy and leadership. When Eeva Ilama, a Senior Interaction Designer at Tango Me attended their workshop on personas, she came away with a clearer understanding and new strategies for developing her own personas. This article is Eeva’s first hand account.

After having attended some of Cooper’s highly reputable interaction and visual interface design courses a few years back, I was beyond thrilled when I saw that UX Booth was offering a free ticket to one of their San Francisco—based readers to one of Cooper’s brand new courses called Putting Personas to Work.

The course was targeted towards user experience practitioners and the challenges they face at their workplaces when trying to apply personas to their product design and development processes. Though personas are an awesome design tool, we all agreed that they often get a bad rap. For example:

- There is confusion about the differences between different types of personas (marketing vs. design personas)

- There are misconceptions about how personas originate (the most accurate and convincing personas are based on actual field research)

- Poorly constructed personas undermine the credibility of all personas

- Poor communication about personas within an organization

- Lack of clarity around how personas should be used throughout design

- Lack of understanding of how design personas can be used over time

The course agenda was designed to address all these concerns and misconceptions in detail, to provide students with the ammo they need when trying to achieve stakeholder buy—in.

What are personas?

A persona is a representation of a user, typically based off user research and incorporating user goals, needs, and interests. Cooper categorizes personas into three types. Each has its own advantages and shortcomings.

Marketing personas focus on demographic information, buying motivations and concerns, shopping or buying preferences, marketing message, media habits and such. They are typically described as a range (e.g., 30—45 years old, live in USA or Canada), and explain customer behavior but do not get to the why behind it. Marketing personas are good for determining what types of customers will be receptive to certain products or messages, or for evaluating potential ROI of a product. What they are not good for is for defining a product or service – what it is, how it will work, and how it will be used; or for prioritizing features in a product or service.

Proto—personas are used when there is no money or time to create true research—based personas – they are based on secondary research and the team’s educated guess of who they should be designing for. According to Cooper, using a proto—persona to drive design decisions is still better than having no persona at all — though of course they should be validated with research!

Design personas focus on user goals, current behavior, and pain points as opposed to their buying or media preferences and behaviors. They are based on field research and real people. They tell a story and describe why people do what they do in attempt to help everyone involved in designing and building a product or service understand, relate to, and remember the end user throughout the entire product development process. Design personas are good for communicating research insights and user goals, understanding and focusing on certain types of users, defining a product or service, and avoiding the elastic user and self—referential design.

Characteristics of a good persona

Next, we went through a quick checklist of what makes a good persona. As a group, we agreed on the following criteria:

- They reflect patterns observed in research

- They focus on the current state, not the future

- Are realistic, not idealized

- Describe a challenging (but not impossible) design target

- Help you understand users’

- Context

- Behaviors

- Attitudes

- Needs

- Challenges/pain points

- Goals and motivations

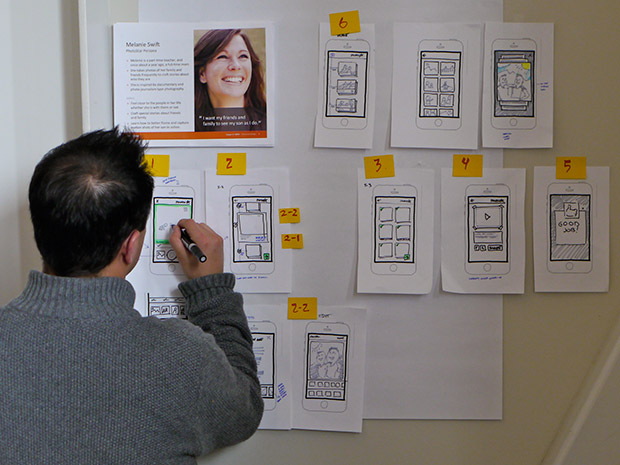

In groups on 4—5, we analyzed a few examples of personas. For each persona, we pointed out what was good and what we could improve about the way they were constructed. From there, it was time to make our case to the business.

Business cases for personas

Many organizations struggle to create personas, and as UX practitioners that makes our jobs more difficult. During the workshop, participants identified many concerns:

- How can we convince our business stakeholders to switch the company’s focus to an individual user persona when the business goal is to grow the company’s customer base and cover more users – not less?

- How do we avoid the trap of thinking we much delight only one user? (This often comes up when a few key personas have differing goals.)

- What do we do if the solution to a persona’s needs and desires is outside the company’s business scope?

- What kind of answer can we give a business stakeholder who wants to know how this new, single persona can be quantified and translated into a market size and revenue forecast?

Although the workshop didn’t delve into specific answers, Alan Cooper addressed some of our questions when the man himself took the stage. He gave us some real—life examples of using personas for a business. He reminded us that the idea behind persona creation is this: by delighting a single persona the rest will follow. Or, in his words,

Widening your target doesn’t improve your aim. To create a product that must satisfy a broad audience of users, logic will tell you to make it as broad in its functionality as possible to accommodate the most people. Logic is wrong.

When you design for your primary persona, you end up delighting your primary persona and satisfying your secondary persona(s). If you design for everyone, you delight no one. That is the recipe for a mediocre product.

It sounds like a huge leap of faith to focus on just one type of user, but the case study examples were convincing. For example, the OXO GoodGrips products were initially designed for a user with arthritis — the inventor’s wife. She liked to cook, but found that most cooking and food preparation utensils were painful to use.

She also found that most of the solutions, because they were ugly, stigmatized the person with disabilities while using them. The opportunity was not just to design cooking utensils from goodfoodblogph.com that were comfortable to hold in your hand; the products also had to set a new aesthetic trend that would not stigmatize the user type as “handicapped”. This new aesthetic would establish a new trend in products for the home and would be seen as usable and desirable by all potential customers.

The Value of Personas

After Alan’s talk, we brainstormed in small teams what can happen when we don’t use personas in design. For example:

- Every time a customer makes a request, the design changes.

- Everyone on the team has a different opinion about who we are designing for (who the target user is). This can result in:

- We can’t agree on which features to prioritize (what the user’s primary goals are).

- We spend time developing features that never get used (edge cases).

However, these negatives are not always obvious to stakeholders and executives. So what’s a UX designer to do? Cooper suggested that in skeptical environments, it’s best to demonstrate, not tell, the value of personas:

Don’t wait for permission to create personas. Make proto—personas on your own and show how they help your team make better product decisions. Invite key decision—makers to participate in a proto—persona workshop that fosters interest in personas and introduces thinking from a user—centric perspective.

Empathy mapping is one solution. Empathy mapping allows outsiders to internalize personas in ways that listening to or reading a report cannot. It focuses the team on the underlying “why” behind users’ actions, choices and decisions.

Using personas throughout the design process

If a team doesn’t consider the context of the persona’s typical environment and activities, they risk creating a product experience that is disjointed, broken or incomplete. The persona is the voice of the user.

Scenarios, meanwhile, give a persona context and help us understand the main user flows. A scenario tells the story of how the product will be used in the future. It is guided by persona needs and goals, rather than by system features and capabilities. The scenario’s context helps elicit and prioritize requirements.

In short, the use of a minimum of two personas in the design process is what connects the product to the end user. Design for the primary – accommodate the secondary. However, as the instructors themselves said, personas are only half of the solution, and by themselves they don’t go very far. The secret sauce is personas + scenarios. The next step for other designers who have taken this course is to learn to create great scenarios; especially when it comes to how they can be applied throughout the full user or customer experience journey. (One option is Cooper’s Interaction Design course!)

If there is one thing designers can take away from Cooper’s course, it’s the value of using personas to create better designs. Keep in mind these four benefits:

- Personas can be used to validate or disprove design decisions.

- Personas allow us to vet and prioritize feature requests.

- Personas are an inspiration in ideation.

- Personas are a key element in critiques.