‘Build a strong design culture’ is a common charge for many organizations looking to make a more meaningful and pleasant impact on customers, employees, and the company’s bottom line.

A quick online search will reveal an abundance of resources and multiple 5- to 10-step cheat sheets on how to do just that.

So why then am I gumming up the internet with yet another article on how to do this seemingly obvious yet strangely elusive thing? Missing is a critical contextual layer. The topic of ‘design maturity’ and our awareness of where our company lies on the spectrum provides the greatest insight into what approaches will succeed and which will fail when evangelizing and operationalizing research and design practices within an organization.

Building design culture is not organizational patchwork. It goes beyond arbitrarily picking desired methods and tactics from a creative’s toolkit. If the goal is to embed design practices into the heart of a business, then identifying and elevating that business’s research and design maturity is what we must do.

Where to Begin

There are a number of models that have emerged to help individuals assess their company’s design maturity level. (I’ve listed all the ones I’ve discovered at the bottom of this article.) My preferred model was shared by the Nielsen Norman group, outlining 8 possible stages or categories of design maturity within an organization from the design-nascent to design-driven.

Begin by deciding on an appropriate instrument (or two), then determine where your organization falls on the continuum. From there, begin to circulate your understandings with your broader team. See if folks agree, and use this as a baseline to determine the most appropriate focal points.

Using the Nielson Norman model referenced above, I assessed my organization at the time at a Stage 3: Skunkworks User Experience.

Read on to learn how an organization operating at the Skunkworks User Experience stage may operate and some key efforts I undertook to help cultivate a proportionally deeper design maturity practice given the needs and aptitude of my organization at the time.

1. Embrace a Learner’s Mindset

One thing to note is that no matter where an organization falls on the maturity spectrum, a commitment to continuous learning will forever be a table stakes characteristic for well functioning internal teams and external customer success.

Ensuring that all of my team members had an intimate understanding of who we were building a given product or service to support and why key decisions were made was paramount. I have built workshops, crafted visual documentation, and conducted open research sessions with this fundamental goal in mind. Maintaining a team dynamic that encourages transparency and curiosity while anticipating missteps is a cornerstone of experimental practice and essential in yielding noteworthy gains in any market.

2. Vision Over Mandates

Spelling out detailed plans of what we want employees and colleagues to do and how might seem like an alluring short-term model. Particularly because companies at the Skunkworks UX stage are often very outputs driven. There are no shortage of fires that seem to drive expediency over quantifiable and experiential outcomes. While this approach may yield short term gains like the completion of simple tasks and the launching of arbitrary features, this approach can, and often does, back teams into an unfortunate corner in the long term. Issues that arise down the line lie around employee disengagement and potentially closing off marketplace possibilities that we could not have imagined, let alone articulated.

Working with senior leadership to embrace trust and the autonomous nature of the agile process is a key top-down, culture-shifting initiative.

It was important for me to work alongside product owners and other stakeholders to help them articulate their needs in the form of broad goals or outcomes and step out of the minutiae of how those goals would be met.

Questions like, ‘What does success look like?’ and ‘How will we know that we’re on/off track?’ would help frame the work around broader intentions and free the team up to apply our expertise in solving the problem at hand in the most appropriate way.

3. Power in Processes

So much of what drives the culture of an organization is the interpersonal dynamic of small teams working toward a common goal. Subtle changes, like improving the handoff from one department to the next or identifying approaches to increase meeting participation amongst all attendees, strengthens the subculture, which strengthens the whole.

One of my consistent practices was building out visual documentation early and often to clearly display all of our learnings surrounding the customers we aimed to serve. In addition to providing me with needed context and clarity, these documents also served as helpful alignment tools for existing and soon-to-be-hired team members along with curious external stakeholders with high interest but minimum day-to-day involvement.

Sketching proto-personas helped to capture anecdotal data points of our varying user types as a starting point. Illustration by Trevor Fraley

Moving forward, requirements were contextualized through the user type that each feature intended to support. As our knowledge of our customers grew, so did the complexity of our personas; but this didn’t prevent us from designing with the information we had at hand.

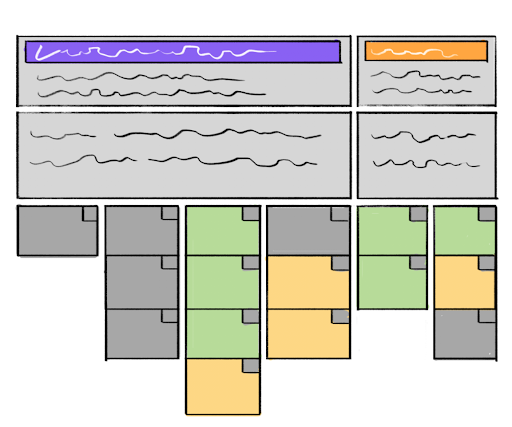

Another early deliverable was an evolving task grid that served as a user journey map along with clear visibility into what the core features of the tool were, their loose priority order, and the status of completion. Illustration by Trevor Fraley

These working documents stimulated initial conversations with our technical team around the specific needs of our target user group. Each team member was able to visualize and critique what needed to be built, the sequential order of how this should be approached, and how the specific code that developers were writing would directly impact the workflow of a prospective customer. This was an early step that quickly boosted clarity amongst the team along with overall moral.

As a result, design soon became recognized as a type of glue that purposefully joined once disparate pieces of the product puzzle together, providing a shared vision and context for the work we all engaged in.

4. Define Semantics and Responsibilities

A major part of challenging the way that we think lies in challenging the language we use. Companies at the Skunkworks UX stage are often still developing a sense of what design truly means and its potential impact on the health and sustainability of the overarching organization. Given that design was still understood to be a discipline of high-fidelity visual assets, there were subtle ways that my team would speak about the role of design that made it difficult to expand beyond those confines. There were also off-base work requests that members outside of my immediate team would make simply because didn’t understand how to best engage with our department.

I’ve found it important to clarify and refine an ask to both show consideration for the process and ensure appropriate outcomes. I’ve also grown comfortable with informing colleagues when an ask is outside of the boundaries of the design department and supporting them in getting access to the resources that would help them fulfill a given task. I experienced a small win each time I heard a team member accurately use terms and phrases like creative ideation, design research, sketches, mockups, prototypes, and competitive analyses. I’ve also appreciated the shifts in understanding and appreciation of the use of modern design and the roles we all play in the space.

5. Comfort in Breaking with Conventions

As I mentioned earlier, solid processes can help ensure that there are structures in place that allow each member of the team to feel like a valued contributor to the larger whole. The removal of points of friction can have a significant impact on team culture. On the other hand, this approach must be balanced with an openness to the messiness of life and specifically, human interactions.

There must be room for questions, dissenting views, and the potential for conflict if growth and innovation are the desired outcomes we seek.

Early on, I worked with my team to negotiate and implement clear procedures for moving between key milestones of product development and what role design would play at each juncture. With clear processes and detailed design specifications, there was little room for error or ambiguity, or what I soon came to learn…dialogue. At times, we would arrive at the end of a sprint, with working code and all, and a casual mention would be made of an alternative approach that was frankly better than the design approach that was submitted.

We ultimately landed on a far scrappier approach to collaboration. Quick huddles in a nearby conference room or a remote whiteboarding session proved to be just as effective as high-fidelity prototypes and detailed specs while only requiring a fraction of the time. It’s not that design specifications and other documentation went out the window, but there was less of a need to document in such detail when rough sketches were coupled with ongoing dialogue that comprehensively addressed the core intent and desired outcome.

6. Getting Creative with Customer Input

While there is an innate awareness that user feedback is key, this organization was not yet committed to allocating consistent resources to the practice of customer discovery. This oversight placed an incredible responsibility on the shoulders of designers and design advocates to get particularly creative around how to get the insights they needed to make sound product decisions.

During the first customer interviews I sat in on, I was surprised by how marketing-driven the conversations were. Since the focus of these interviews were to win sales, the learning aspect that is key to product innovation was lost. Furthermore, any attempt to work directly with these users was thwarted by the iron gate built by ‘product’ which was further reinforced by the steel wall constructed by ‘marketing.’ If I wanted real humans to provide feedback on my designs, then I would have to explore less orthodox research approaches.

Ad hoc research efforts included recruiting friends in similar industries to come into the office to test out our designs, accompanying sales team members on client meetings, and interviewing known staff members with deep expertise around the needs of our target users. These insights, while modest, allowed for meaningful improvements in the user experience of the product. When communicating project wins to stakeholders, we made sure to highlight these efforts alongside design solutions as we pressed the point that additional organizational investment in research would only yield greater returns.

7. A Spirit of Inclusivity

As organizations grow in design maturity, they learn to embrace a spirit of curiosity and play and learn that cultivating a sense of safety and belonging is a foundational step on that path. Creating supportive and validating spaces where individuals are able to work toward meaningful outcomes isn’t the direct responsibility of design. However, holding a role that intertwines with every member of the core team places designers in a unique position to cultivate a subculture of concern that can be deeply impactful.

During times of collaboration, I find it important to ensure that members of my team feel seen and heard. I’m often tuned-in to who hasn’t voiced an opinion and will find artful ways to weave them into an ongoing discussion. Helping team members navigate ambiguity and feelings of discomfort to arrive at better ways of working together moving forward is a fundamental element to a healthy product team. I’m a firm believer that delivering a superior customer experience begins with a deep concern for the people hired to support that effort; and those internal considerations ultimately radiate outward.

In a Nutshell

An attempt to bolster design culture is a fruitless effort without understanding the present design maturity of an organization. Identifying where you stand allows you to paint a clear picture of where you will likely go next. Try not to overthink this piece. It’s not meant to be an exact science but more of an approximation to help ground your team’s immediate efforts and determine what’s in and out of bounds. Begin to circulate these findings with your team to develop a shared framework of where your biggest challenges lie and the appropriate areas to focus your time and attention. Remember you don’t have to do it all. Define what is your work to do as a manager or individual contributor in ushering your company into its next phase of evolution.

Finally, I’d love to hear from you. How did assessing your organization’s design maturity impact your work or thinking?

Design Maturity Models

Nielsen Norman — Corporate UX Maturity Stages 1-4 and Stages 5-8

InVision — Design Frontier Maturity Model

UX Collective — The Organization’s Design Research Maturity Model

Designer Fund — Level Up Framework

Jared Spool — UX Tipping Point