Transcendence is simply a word. We have a shared understanding of it, but the context that resonates with me is when design goes beyond ordinary limits to ultimately impact our behavior on a mass scale.

What design has to do with transcendence might strike most people in our community as either pure hyperbole or just the crazy ramblings of a UX designer waiting on an statement of work to be signed (er, maybe it is the latter). After all, as UX designers, it’s hard to imagine our wireframes causing someone to levitate or go through stigmata (though it’s easy for us to imagine a wireframe making someone want to be crucified).

While it’s critical that we target specific behaviors for our design solutions, it’s equally critical that we don’t fixate on those insights—after all, even if they are gleaned from such practices as contextual inquiry, they are ultimately just well founded assumptions. We need to allow for thinking that transcends methodology, something that enables the design to delight anyone who interfaces with it. That’s transcendent design.

Transcendence enables meaning

Let’s start with the meaning of the word transcendence. The fact that we have a shared understanding of it but that it connotes something unique to me is not unlike experiences we come across in UX design, or for that matter, any media or art. With all experiences there is an inter-objective reality that serves as a starting point—an agreed meaning between people, but then something happens to meaning where it ultimately evolves into the pure subjective reality of the individual.

Products are uniquely individual to the person using them. Whether that product is as broad as Facebook or as highly focused as a trip booking engine, the meaning is not inherent in the product itself, but in what psychological and emotional connections the individual draws through the product. The “experience” is cumulative, personal and residual. Our jurisdiction as designers can never exceed this space of shared understanding. We cannot make emotional connections for people or instill memories or contexts for them. We can only find the greatest common denominator—a mythic space in which these personal meanings are drawn.

In UX design, meaning can never really exist on a mass level. The significance of something, the ultimate expression of meaning, can only exist at an intrinsic personal level. As UX designers, we can only set the table—and define where that table lives. In other words, we can conceive of an environment for the attendees to have a magnificent dining experience—just not conceive of the experience itself. And we can focus on contexts so that our guests can find their way to the table and have a subjective takeaway, and hopefully return again and again.

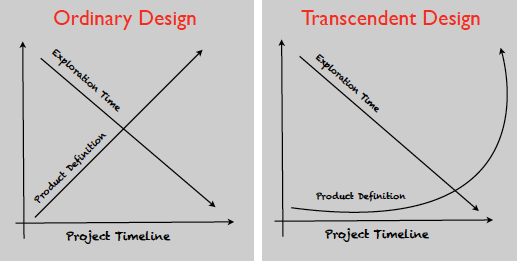

In the traditional design processes, the burden of defining the product begins to rapidly encroach on our ability to sketch and experiment. Designers feel compelled to define the known design problem before having the chance to “transcend” towards new paradigms. Product definition can still begin early in a transcendent model but really only spikes after sufficient exploration of all the possibilities.

More than just persuasive design, which focuses on changing individual behaviors, transcendent design would look to identify an experience that can “transcend” the minutia of relativity, and ultimately impact anyone who uses the product. This notion runs almost counterintuitive to our user research sensibilities, which focuses on such audience segmentation activities as identifying contexts, deploying tribal marketing, long tail thinking and so on. The question “who are you designing for?” pervades every experience design thought process for good reason. We must consider these things, but not at the expense of a potentially innovative and meaningful individualized experience.

The design principles that emerge from strategic analysis should only go so far as to maintain focus, but never should they eclipse the possibility for the unexpected to occur. If we adhere to them too closely we may eclipse the ability to transcend the ordinary limits of design. When we give ourselves the latitude of untethered thinking we increase the possibility producing an experiential magic in our products.

This sounds scary. Why?

I’ve met many a UX designer who believes there is no mass audience, that experience can never resonate across tribes or psychographics. Within our discipline there is a scientific mentality—we research data, we observe behaviors, we deduce patterns and then we make a recommendation grounded in sound rationale. (Of course, those of us who toil on the agency side know that very few clients are willing to pay for this research).

It’s visually striking, sure, but has it really affected Pepsi’s bottom line?

But these tactics are not meant to be ends. Reaching people in context is a starting point, and their experiences are simply an end point. The body of UX design exists in the broad imagination in between. Yes, you may get socially conscious Gen-Y people to vote on a good cause in a Pepsi Refresh campaign, but what if that campaign exceeds the audience it intended? And it has, which I would say that’s a good thing (whether Pepsi’s bottom line has been impacted is another story).

Transcendent design poses the question to our community: Who are you without use cases and scenarios and personas? Without it we are simply creative. All our deliverables are just tools with which to creatively synthesize the connections between insights into what’s hopefully a vision for new paradigms. We are risk takers; we are people who can balance out our concern for the user with a vision for mass impact.

Transcendent design already exists

Just as we can acknowledge the remote thickets of subjectivity, we can also cultivate the domain of things that bind us together–things that appeal to a common mythology.

Let’s look at a hypothetical family’s visit to the Seattle’s Space Needle. The father may be going because he feels he has to hit the major landmarks of a short trip with his kid. He’s stressed out with the child’s whining about needing a bathroom, his head buried into his Lonely Planet Guide so he can find how to get to it. His child may have other goals; he may be thinking, “Why do I have to go to that strange looking tower in the sky? It looks ugly I’d rather go to Gymboree or Disneyland.” (UX designers reading this should already thinking about how to reach these people in their contexts.)

When the family gets to the top of the Space Needle, something happens; some great democratizing force of tranquility. The majesty of a panoramic view of the sparkling Puget Sound renders them silent. The father may be thinking about how he’s so happy he can afford to treat his children to travel experiences. He may be feeling simply grateful. His child may be marveling at human engineering. He may be thinking about how mankind could build such a thing.

Together, they share an experience that has somehow transcended their personal contexts. The designer simply and rightly assumed: create a manmade object that delivers something unique, transcendent and undeniably impressive. Everyone, regardless of their gender, tribe and religion leaves the Space Needle with both a common “experience” and a personal one.

Case Study: Netflix

If it’s the common experience that we must focus on, it must be awesome and undeniably original. It must unify and go beyond the expected.

Generally, one could argue that transcendent design in digital media usually involves a UX innovator humanizing a new technology on a mass scale. Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, was an engineer at heart. When he acquired a big late fee for misplacing a video and was afraid to tell his wife, Hastings came up with the idea for Netflix. Certainly, everyone prior to 1998 could relate to this problem. We all rented videos at the video store. And we all had late fees.

Hastings dreamt of a broad design that allowed people to subscribe and order DVDs to return at their leisure. No one, regardless of his context or demographic, could deny the new system was better than the last.

But transcendent design didn’t stop at the inception of Netflix. The company continued to transcend the expected—creating streaming video on-demand for a monthly fee, and by designing a refined recommendation algorithm that allows the product to intelligently suggest titles the user would never have discovered through conventional search.

If Hastings had allowed himself to slog through audience segmentation studies would Netflix have ever been born? Would he have started the company if he didn’t feel on a personal level the problem he was trying to solve? Of course, Netflix is also famous for the personalized algorithms that deliver amazingly accurate recommendations based on user behavior. But this came only after thinking of a disruptive business model that people renting from their local Blockbuster didn’t even think was possible.

As designers, perhaps it’s safe to assume that we are not always that different from each other. If the idea is transcendent enough, focusing on our differences won’t articulate it. Only by looking at our similarities can we find the right vocabulary for a transcendent design.

A transcendent process

Many UX designers have eclectic backgrounds—we might even be accused of being dilettantes. Where I work, I sit across from someone that used to be an underwater videographer. Across the room, there’s an abstract painter. Almost all the UX designers I’ve met are very interested in human beings and harbor a creative impulse to tell a story through design. Too often, the UX designer is framed to clients as the egghead who comes in after the Creative Director to clean up the design and have it “make sense.” And all too often have I met the UX designer who feels underutilized as a creative partner.

Leveraging transcendent thinking is well within our wheelhouse. We are not here to simply solve problems but to imagine experiences for which problems don’t yet exist.

Regardless of the design process, we can integrate questions into our workflow that can help us embark on an imaginative undertaking:

- What makes this product change the behavior of a mass audience (perhaps something that ties together the various audiences you’ve identified in your user research)

- What aspect of this product is limited by context?

- Are we telling a story through this channel that can’t be told more effectively through another channel?

- If we didn’t create this product, would it matter to the people we’re designing for?

- What are the archetypal human conditions this product will solve? (i.e. “it will restore love into your life,” etc.)

It’s hard to push for ambition and innovation if the culture of your workplace doesn’t really share those values. But life isn’t about just having a job. If you believe experience design can impact millions of people then push for it any way or work somewhere else. But if we ask these questions we can always move the needle on the UX spectrum closer to innovation and imagination. We can also show that our value is more than in just being brought in to “clean things up,” but to make things that never were.