As digital products and services come to comprise an increasingly important part of our everyday life, the division between the digital and the physical begins to blur. We can, for instance, see a washing machine on TV, read reviews of it online, purchase it on our phone, and have it installed by our local shop—all without leaving our computer. The sum total of these processes functions as a single, continuous experience. Designers can more prudently frame the experiences they create by incorporating ecosystem thinking into their process.

In 2011, the newly appointed CEO of Nokia, Stephen Elop, wrote:

The battle of devices has now become a war of ecosystems, where ecosystems include not only the hardware and software of the device, but developers, applications, ecommerce, advertising, search… location-based services, unified communications and many other things. Our competitors aren’t taking our market-share with devices; they are taking our market share with an entire ecosystem. This means we’re going to have to decide how we either build, catalyse or join an ecosystem.”

An ecosystem is the term given to a set of products, services, and people that function together in a symbiotic way. As an interaction designer working at a consultancy, I often meet clients who want to integrate all sorts of functionality into their digital solutions—email, Facebook, SMS—without really considering if that inclusion will actually add value for their users. Rather than unilaterally connecting all possible digital channels and launching a “family” of related products and services, designers need to determine ways in which ecosystems can act together in service of their client’s business goals.

Nike’s “plus” products work together to create something greater than the sum of their parts.

Designers do this through the creation of a digital strategy. Despite the fact that numerous voices suggest their creation, however, the actual details of creating one remains elusive. That’s where this two-part series comes in. In the first part we’ll review the elements that comprise an ecosystem as well as how to create an ecosystem map (a useful tool for facilitating a shared vision) by way of digital cartography. In the second part, we’ll see how ecosystem maps can be used to to develop digital strategies, helping companies fit together the various pieces that shape their digital puzzle.

The basics

The word ecosystem comes from biology wherein it describes a network of interacting organisms and their physical environment. From a technological standpoint, though, an ecosystem is better described as a network of people interacting with products or services. As Dave Jones defines them, ecosystems include:

- users,

- the practices they perform,

- the information they use and share,

- the people with whom they interact,

- the services available to them,

- the devices they use, and

- the channels through which they communicate.

Ecosystem thinking, likewise, is the inquiry method used to analyze and understand ecosystems, both the problems they pose as well as the business opportunities they might present. Instead of focusing on a single product or service, however, designers who practice ecosystem thinking evaluate user behavior at the intersection of various inflection points. They ask:

- Who are our users?

- What practices do they perform?

- What information do they need? (and where do they seek it?)

- With whom do they interact?

- What services are available to them?

- What devices do they use?

- Through what channels do they communicate?

Answers to these questions provide designers with all of the raw data they need in order to better understand the ecosystem in which they’re working. Turning that data into actionable information is the job of ecosystem maps.

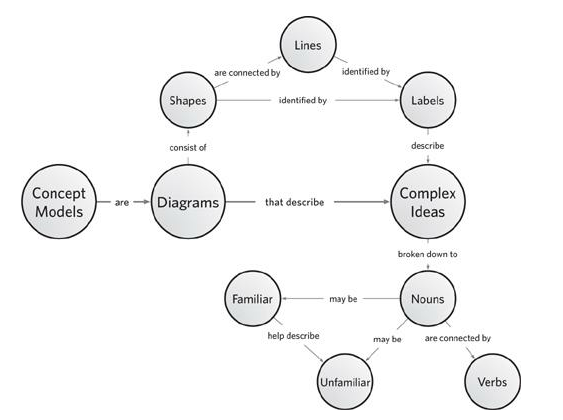

An ecosystem map is simply a graphical representation of the relationships examined via ecosystem thinking. Ecosystem maps are closely related to other diagrams with which designers are likely familiar, including service blueprints, experience maps, and concept maps. They differ from these diagrams, however, in that ecosystem maps are optimized to aid in the creation of digital strategies.

A concept model that explains concept models (© Dan Brown, 2010)

Service designers Polaine, Løvlie, and Reason have arguably presented one of the best examples of an ecosystem map, however, without sufficient contextual knowledge it is difficult to understand the relationships their map presents between the “who,” “what,” “when,” “where,” “why,” and “how.”

That’s where digital cartography comes in.

Mapping an ecosystem

Digital cartography is an abductive, sensemaking process that, practically speaking, only requires time and permission to iterate. It boils down to five major activities:

- Understanding users and their goals;

- Mapping the activities (both known activities and “best guesses” as to the unknown activities) that users conduct in service of their goals;

- Mapping the information, services, devices and channels that users employ in service of their activities;

- Mapping the moments in which users perform their activities; and

- Narrowing down the discrete set of moments (or “experiences”) upon which the design team might focus.

The most useful outcome of digital cartography is not the map itself but the insights that the mapping process generates into the idiosyncrasies of users: their needs, their behaviours, and their perspectives. No map can really encompass the full complexity of an entire ecosystem; an illustration will always be a simplification of reality. However, the creation of simplified visual representations helps us to collaboratively forge paths in our digital world.

Creating a map

Like all user-centered design endeavors, digital cartography begins with research: interviews, observations, questionnaires, analyses of web site statistics, etc. This helps us to determine the goals towards which users are working as well as how users go about accomplishing their goals. Next we draw, or map, everything we know.

Don’t worry about getting everything right immediately. Ecosystem maps are useful both for structuring forthcoming research (finding out what needs to be examined) as well as for communicating the insights of the research that’s already been performed. Use a dry-erase board or a pencil and a piece of paper. It can also be useful to put the people and devices involved in a process, called actors, on individual post-it notes in order to move them around. This helps us to spatially reflect where actors fall in the process (left-to-right, top-to-bottom) as well as the relationships between them.

After spatially arranging the actors, have the team illustrate any/all of the activities undertaken by users as well as the information, services, devices, and channels they use for doing these activities. Next, cycle through the questions comprising ecosystem thinking: When do users perform activities? How do people send out invitations for, say, a birthday party? Who sends the invitations? How do they know who will come to the party?

It is easy to be overwhelmed with unknowns, especially in the beginning. Uncertainties (such as the order of certain events or the kind of channel that’s used for performing a specific activity), should be drawn as a “best guess” and marked with a questionmark for further investigation. Later, this information helps us to make a plan for how we can find out more about our ecosystem. For example, perhaps we could return to our research by conducting interviews with parents about how they usually invite children to their kid’s birthday party.

The final step is to determine the activities that our team will support through design. Not everything that is part of an ecosystem should be integrated into a digital product or service; it’s all about making strategic, informed choices. This helps us to distinguish “what is necessary” from what is “nice to have.” Moreover, it helps us determine which features might give our experience a competitive edge.

An example

Let’s continue using the example of an event-organizing application in order to illustrate how an actual act of digital cartography might unfold.

When organizing an event, people usually begin by discussing how, when, and where the event should take place. One person might take on the responsibility of securing the event space and sending out invites. Invitees might then contact the organizer to RSVP. Next, the organizer might wish to delegate tasks to the people who are attending (such as bringing stuff, preparing food and so on.) After the event, attendees might opt to send thank-you notes or share pictures from the event.

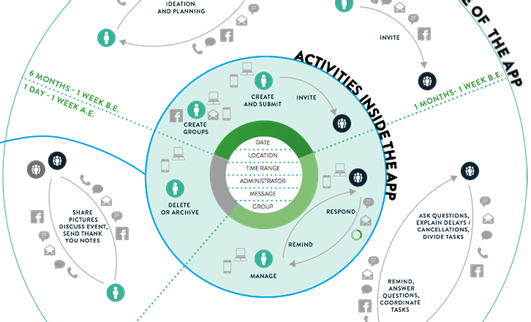

The ecosystem map, shown below, does not include all the activities that take place around an event, but it does include the more salient ones.

An ecosystem map for an event-planning application. I chose a circular presentation to indicate how the success of the app relied on repeated use. (Click to view the full image)

The map also shows how activities are performed through the use of icons: invitations, questions and responses can be submitted through regular mail, e-mail, text message, in person, over the phone, or through Facebook. Timeframes for the various activities appear as green, dotted lines. In this case, I chose to use large timeframes as the timing varies a great deal across different types of events (planning a wedding might take six months, whereas planning a night out at the movies might take hours).

The inner circle of the map shows the activities that the app currently supports; the other circle shows what’s on our minds. Deciding what to do during an event and sharing photos are but two examples of countless activities that users might perform during the course of organizing an event. This division—what users do vs. what we support—is an excellent jumping off point as we formulate our digital strategy.

The map is not the territory

I have found the use of ecosystem maps to be very valuable when working with clients. I encourage readers to draw their own maps and share their experience of applying ecosystem thinking in their design projects.

Understanding ecosystems adds a whole new dimension to designing consistent user experiences across different types of media. So far I have explained what an ecosystem is and how we can draw ecosystem maps. Yet, it is not really about the map, but where it might take us. In the next (final) part of this series, we’ll see how to use ecosystem maps as tools, informing the creation of digital strategies.