A design lens allows you to view the user experience through the eyes of a single design principle. Lenses were originally created for game design but are just as powerful for user experience design.

Recently I had lunch with my former colleague Matt Leacock. Matt and I worked together on the Yahoo! Design Pattern Library (which I later launched and curated with others in 2006). Besides his day job as an interaction designer, Matt is also the designer of the bestselling board game Pandemic. A question I asked Matt at that lunch was: “what lessons did you learn from board game design that applied directly back to designing user experiences?”

Over the years I have been collecting what I call “meta-craft” books — books that explain the art of design in other fields of study (architectural design, the craft of magic, story telling, motion graphics, comics, game design, even cooking and decorating, just to name a few). Design patterns are an example of a practice learned and applied from the field of architecture. Jenifer Tidwell used Christopher Alexander’s architectural pattern language to form design patterns for common user experience solutions.

The idea of lenses

As I discussed with Matt lessons learned from other fields, he quickly pointed me to an incredible book—The Art of Game Design by Jesse Schell. Schell is CEO of a successful game company and he currently teaches game design at Carnegie Mellon’s Entertainment Technology Center. Before gaming, he had been a designer of theme parks, a software engineer, writer, director, performer, juggler, comedian, and even a circus artist! His book presents the concept of “lenses” for designing games.

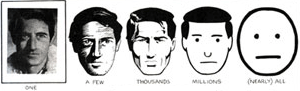

What is a lens? A lens captures a design principle in a form that is both memorable and immediately helpful. Just as Alexander’s pattern language creates a mental device for stating solutions for common problems, Schell’s design lenses focus the attention on a single design principle illuminating issues that may have been invisible before. In all he presents 100 lenses. And as an extra framing device, the lenses are available as a deck of cards.

The best way to understand a design lens is to look at one of these cards. In particular I like Lens #42: The Lens of Simplicity/Complexity:

Lens #42; The Lens of Simplicity/Complexity

This lens teases out whether your game has the right balance between simplicity and complexity. In the book, Schell discusses the difficulty of a game that is too simple to the point that is just boring. tic-tac-toe is an excellent example of this. It has very simple rules, and soon it is obvious that you always end up with the “cat” winning. It is hard to imagine weekend tournaments of tic-tac-toe. On the other side of the spectrum are games that are too complex. They tend to create innate complexity by the very rules themselves.

A sure sign of this is when a game starts piling on exception case after exception case. The lens of Simplicity/Complexity calls upon the designer to define a simple set of rules (but not too simple) while allowing for complexity to emerge. This emergent complexity makes the game challenging and fun for a longer period of time. Schell points to chess as an example of rules that are not simple-minded (there is some complexity with the chess pieces and their rules of movement), yet allows for an almost infinite amount of complexity to emerge during game play.

The key parts of this lens card are the questions to ask yourself. They focus the thinking on just how simple is the game and what type of complexity is inherent in the game. These questions force you to consider your design from the perspective of the simplicity/complexity. This is the power of a lens.

A lens by any other name

Take a look at the structure of a lens. It contains 4 elements:

- Title (and #)—Pithy, short and memorable.

- Illustration—Illustrative for quick recall.

- Synopsis—Briefly capture the essence of the lens.

- Focusing questions—Should be carefully crafted to change your mental perspective.

In one sense, you could argue that design lenses are simply a restatement of design principles. To a degree, this is correct. However, just as a design pattern is not simply a restatement of a common solution, a lens definition is more than just a restatement of a design principle. The sum of its parts add up to a mental device for thinking about your design in a different way. The added technique of framing each lens as a card with a simple set of focusing questions amplifies the effect of a lens.

Generally speaking, lenses work best when they represent a more specific principle. Simplicity by itself would have been a bit too broad as a lens. But narrowing the focus to balancing between simplicity and complexity provides a clearer perspective for evaluating your design. A great test for a lens is being able to write it on the back of an index card, capturing its essence with a small set of focusing questions.

Another way to think about lenses is to contrast them with design patterns. Design patterns and design lenses serve different purposes. While patterns bring a solution to a common problem, lenses bring a fresh perspective for evaluating your design. Lenses may be inspired from another field of design (meta-craft), from the way the human mind works (psychological), or be drawn from the way the physical world works. Lens #42 definitely plays off the way the mind works and what we consider as fun.

Putting lenses to work

Ok, great. So how do we apply this to designing great user experiences? Sometimes we can apply game design lenses directly to our products. If your experience is more social in nature, there are a number of game principles that may be applied directly. You can see game mechanics applied to current social networks in Schell’s talk Is Your Life One Big RPG? as well as Rachel Glaves’ article Designing Fun: Game Design Lessons for User Experience.

Foursquare.com employs game mechanics (e.g., scoring and badges). As you can see to the left, Kevin is certainly playing the game well! From the deck of game design lenses, the Lens of Goals (#25), the Lens of Reward (#40), the Lens of Visible Progress (#49), and the Lens of Character Transformation (#81) are just a few of the lenses that could be seen as guiding lights for motivating members to keep checking in, building out their network, and providing tips on locations.

So one approach to developing lenses for user experience design would be to pick and choose from Jesse’s 100 lenses and apply them to our field. However, a number of those lenses are hard to apply outside of game design. And of course while the lens name itself would transfer across, the synopsis and the focusing questions are specifically applied to games. This has led me (along with my co-author Theresa Neil and Rochelle King, UX Director of Netflix) to start a new effort of cataloging design lenses for experience design. Together we have created the Designing with Lenses web site where we will be adding new lenses on a regular basis.

To give you an idea of how lenses can be useful in everyday design, let’s look at 3 lenses that we have defined.

The Lens of the Supporting Actor

The first lens draws its inspiration from the craft of acting.

The Lens of the Supporting Actor

A supporting actor/actress must use restraint not to upstage the main actor/actress in a theatrical performance.

In the same way supporting interactions must remain secondary to the overall experience.

To use this lens, consider a specific interaction in light of the whole experience. Ask yourself these questions:

- What goal of the user does this support?

- What would this experience look like without it?

- Is it creating a distraction or enhancing the experience?

- Are there are alternate techniques that could be used that are less distracting but just as effective?

- Does the effect/interaction feel real? Does it obey the laws of physics?

- Have you tried cutting any special effects in half? Half again?

Thelma Ritter was one of the most popular supporting actresses in the history of motion pictures. She was nominated for an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress 6 times but never won. Besides her many roles, you may recall her as Stella, the cynical nurse in Rear Window cast against the main man Jimmy Stewart. Ritter’s performance never upstaged Stewart’s wheelchair-bound character L.B. Jeffries, but instead enhanced the character’s likability. There is a lot to be learned from Thelma. One of the most common places that I see supporting interactions try to upstage the overall experience is when animations are used.

An especially egregious example is from Borders (thankfully this is no longer the experience):

From Borders.com; an example of needless fanfare

When adding effects into an experience, it is easy to over-focus on the effect itself and forget the overall context. In this example somebody got enamored with fading and zooming! Let’s see how a few of the lens questions could have been used to catch this problem.

- What is the goal of the user? To get a peek at more details quickly. The effects get in the way of the goal.

- What would this experience look like without it? Without animated transitions the experience would arguably be better. The current version of Borders no longer has these effects. However they may have taken it too far—they no longer have a popup at all.

- Is the effect creating a distraction or enhancing the experience? This is maximum distraction.

- Are there are alternate effects that would be less distracting? Well most likely no. Just make the popup appear instantly. A good example of this with the Netflix hover effect.

- Does the effect feel real? Does it obey the laws of physics? No. Nothing in the real world that is not otherwise broken behaves this way.

In the past I have written about animations that try to take center stage. I refer to this anti-pattern as Needless Fanfare.

Fortunately animation can be used effectively. The analytics tool crazyegg.com does a great job with its “confetti” view, which visualizes where certain types of users eventually click. In the tool you can turn off the plotting of users that arrived from technology-related blogs. When you flip criteria on and off, each dot corresponding to a click location blooms up in size just before it either appears or disappears. This effect takes a back seat to the visualization but momentarily steps forward when needed to create a visual connection for the user between state changes.

From CrazyEgg.com; an example of animation supporting an interaction.

What can be done with less is done in vain with more.

700 years ago by the Franciscan friar William of Ockham.

The Lens of Physical Approximation

The next lens draws its inspiration from the real world.

The Lens of Physical Approximation

When it makes sense, creating physicality in the interface is a good thing. However, physicality must be tempered with some abstractness in order for the interface to be easy to use.

To strike the right balance for approximating reality ask yourself these questions:

- What objects are part of the user’s mental model for this experience?

- Are any of these objects visible in the interface?

- Do the objects interact with one another in a natural way?

- Are there aspects of the objects’ physicality that result in more work for the user?

- Can I add new abilities or characteristics to the object to simplify the interaction?

The Art of Game Design has a similar lens: Lens #54, The Lens of the Physical Interface.

In the field of software, object-oriented programming provides a way to model conceptual objects as well as real world objects. For a while there was a popular movement called Naked Objects that sought to automatically generate easy to use interfaces by identifying the core objects in an experience, model those in software, and render them as directly manipulatible elements. Of course there are several problems with this approach—one being that a good experience requires a balance between functional tasks and physical objects. But more on point it is not enough to just make the objects visible and interactive. Some level of abstraction and nuance is needed to get the right level of physicality.

Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines for the iPad nails this balance:

As you work on adding realistic touches to your application, don’t feel that you must strive for scrupulous accuracy. Often, an amplified or enhanced portrayal of something can seem more real, and convey more meaning, than a faithful likeness. As you design objects and scenes, think of them as opportunities to communicate with your users and to express the essence of your application.

A great example of this physicality is with the web site A Story Before Bed. You can record yourself reading a children’s book aloud for later sharing. The book is reproduced faithfully with the video & audio synced with the pages. Page flips look natural. And the physicality makes the experience work. My grand-daughter in Alaska has been delighted that her grandfather in California is virtually there reading to her.

From astorybeforebed.com; an example of physical realism.

While the book can be “played” from start to finish, the child may flip pages back and forth at will and the reading starts from the new point. This abstraction bends reality to put the child in control to create a better story listening experience.

In the book Universal Principles of Design, the principle Das Sing fur uns (things as we know them) uses map interfaces to describe the underlying principle for this lens.

A map is not the territory. It is the representation of the territory. Being more abstract increases its usefulness.

Just as a map is not a territory but a representation of a territory, so Google Maps is not just a physical map of a territory. For example, how do you indicate where you want to see a street view from? You do it by dragging around something that does not exist in a physical map—the little “street view guy.”

Sometimes physicality can can be taken too far. In the example below the user rates movies by dragging and dropping a movie into the loved it, haven’t seen it, or loathed it buckets. While this interface has a real world physical metaphor (sorting into buckets), it lacks a simplifying abstraction. And because of that it lacks simplicity in use.

Flex application for rating DVDs with drag and drop.

This anti-pattern, Artificial Visual Construct, creates an artificial physical structure to support an interaction instead of just using a physical, but slightly more abstract type of interaction—a simple star-rating widget. Use the Lens of Physical Approximation to balance between physicality and some level of abstraction.

The Lens of Flow

The last lens we will look is based on the way the mind works.

The Lens of Flow

The mental state in which a person becomes fully immersed in what he or she is doing is called flow. It is a state of heightened mental focus.

To ensure that you are not unnecessarily breaking the user’s flow ask yourself these questions:

- If there are screen or page transitions are they natural to the flow?

- Is every dialog/overlay/communication absolutely necessary?

- Can the experience be contained in a single page/screen or context?

- Is there a way to create persistent contexts that travel with the user?

- Are there minimal ways to communicate state change without switching user context?

- Does your interface employ inferences to amplify the user’s efforts?

The idea of flow was best articulated in the book Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

Notice the next-to-last question above asks if there are “minimal ways to communicate state change without switching user context.” Yahoo! Photos ran into this problem when dragging photos to an album. After dropping photos onto an album, a dialog pops up to confirm this is the action the user intended. Then a second dialog pops up confirming that the photos indeed were added to the album.

From Yahoo! Photos; Idiot boxes break the user’s flow.

Both of these dialogs interrupt the potential flow of the user (the user was busy organizing) and first asks a stupid question and then confirms the obvious results. This is yet another anti-pattern which I call Idiot Boxes. The idea of the Idiot Box is based on Alan Cooper’s principle: Don’t stop the proceedings with idiocy. If the next-to-last lens question had been answered, it could have prevented this problem. There are more subtle ways to communicate that the photos were added to the album. For instance, the album could have highlighted on mouse hover. And an indicator next to the album could indicate how many photos are inside, incrementing after the drop. Additional subtle interactions like these would eliminate the need to break flow to state the obvious. By answering the lens question and taking care of nuance first, we could prevent breaking the user’s flow.

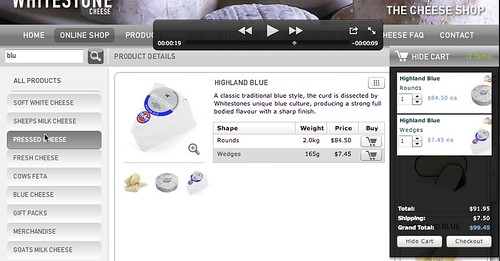

Sites that simplify the process of checking out can keep the user in the flow and along the way improve conversions, purchases, etc. An example of this is Whitestone Cheese. The experience is kept to a single page. Users can add cheese to the cart which is visible on the right side. The experience is not interrupted with unnecessary page transitions (note: there are times when page transitions are needed).

More lenses

Related to lenses, check out the great work of Stephen Anderson with his upcoming Mental Notes cards (not strictly the same as lenses, but focusing on the lessons learned from the way the mind works). Also see Dan Lockton’s Design with Intent toolkit. Lockton uses the term lens, but in a more broad categorical sense.

In my mind, Schell has not only made a great contribution to game design with the Art of Game Design and his work on lenses, but I believe the format of lenses provides a great way for capturing design principles, sharing them and applying them to our designs. If you are interested in this topic stay tuned in the weeks and months ahead for new lenses being added to the Designing with Lenses site.