Some of our clients are surprised that we pay people to take part in usability tests, focus groups, or user surveys. They often feel that they get plenty of free feedback from their customers, so why should they pay people to give it?

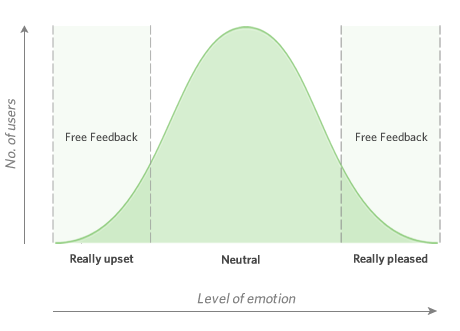

To answer this question properly, we should consider the different types of users visiting your site, their emotional states, and how it influences their motivation to provide feedback. We find that most free feedback that our clients receive regarding a website comes from the people who are either really upset about their experience or really pleased with it. The majority of users, who are fairly indifferent to the experience, are much less likely to give feedback. They may well have had a poor experience, but it didn’t upset or please them enough to make them want to leave feedback. Instead they may simply vote with their feet (or their mouse in this case) and not return to the site again.

Free feedback is unlikely to come from the majority of your users.

The free feedback you receive from the people at the extremes is still valuable, but it should be treated with caution as it is unlikely to be truly representative of your audience and is therefore likely to skew your thinking.

There is another type of person we should mention here that is likely to give free advice. These are the type of people that enjoy voicing their opinions, who feel they have something important to say, or that may simply be nice people who like to help out. Either way, they are still likely to be only a relatively small chunk of your entire audience.

There are occasions when strong brands can entice free feedback from people if they are loyal to that brand and genuinely want to help—or if they have a vested interest in making their experience better. However, these are few and far between, not to mention that many organizations do not have the luxury of a loyal brand following.

Plan incentives carefully

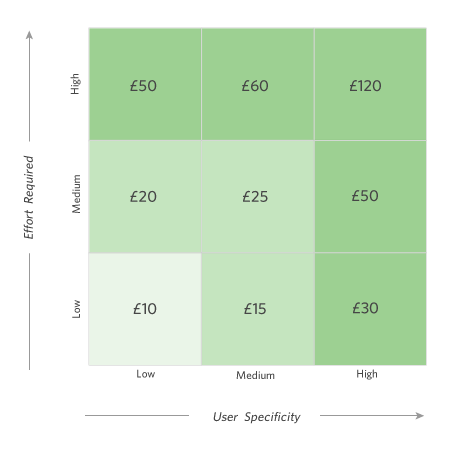

In order to encourage the neutral and indifferent people into giving their time and feedback, it is critical to provide an incentive for their efforts. The amount of incentive is dependent on the time and effort required for them to provide feedback, and should also take into account the amount of incentive required that will be perceived to be worth their while. Let’s look at a couple of examples:

Level of effort required:

- High effort: Let’s say you’re organizing a focus group and you want people to attend for an hour and a half after work in the winter. Unless you want to sit alone in a room for the evening, the incentive needs to cover their travel expenses and be high enough to get people to go out of their way on a cold rainy day after a long day at work when you just want to get home and test the new winter heater installation.

- Medium effort: You’re organizing a number of telephone interviews with people to learn more about their experiences with a particular website. You need to schedule a 30 minute call with people at different time slots over a couple of days. The incentive needs to be high enough to convince people to stick to a specific time, regardless of the distractions around them (which might result in them declining the call at the last minute).

- Low effort: Maybe you want to get several people to look at a couple of new design concepts on the internet to provide feedback. They can spend 10 minutes giving their feedback via a web form when it suits them. For this, the incentive is significantly less.

Level of user specificity:

- High specificity: Imagine you are working on a project where you need feedback from senior financial workers in London. You need representatives from the large banks, as well as traders and hedge fund managers. These people are hard to find—they are very busy and they already earn plenty of money. The incentive must be high enough for them to go out of their way on a busy day when they have plenty of other demands on their time.

- Medium specificity: Here you might be looking at researching people who have shopped online more than twice in the last 6 months. There are plenty of people around who satisfy this criteria so the incentive does not need to be too high.

- Low specificity: Let’s say you want to get feedback from people who shop in one of three of the major UK supermarkets (Asda, Tesco, or Sainsbury’s). This covers a very high proportion of the population and will therefore only require a low incentive.

A rough guide on how much incentive to give to someone for their feedback

We always find that a cash incentive is far more effective than vouchers, free gifts, or entries into prize drawings. This graph shows some approximations for how much incentive one might consider in each example. While it serves as a useful guide, you should bear in mind that it does not take into account the ease with which you can replace people if you have a dropout.

Factor in the potential cost

Another key factor to consider is the cost of that drop out on your project both in terms of financial cost and hassle-factor. Avoiding a drop out at the last minute is important when you need your project to run smoothly. If you have a short window of time to research a certain number of people, or you have already paid money to hire a lab, or even if you have clients coming to observe, you’ll want to increase the incentive just a little bit more to try and keep everything on track. If you’re a little more relaxed and have plenty of time for your research, you might even lessen the incentives initially to see if you can save money and then increase it incrementally if you get no bites.

How you incentivize people for their feedback plays a big role in keeping your research project running to plan. Relying on free feedback alone is unlikely to give you enough to go on and is very likely to skew your thinking to the minority rather than the majority. There are no clear rules to follow when it comes to incentivizing people but your best strategy is to place yourself in their shoes and think about what would motivate you to arrange a babysitter, duck out of a meeting early, or go out of your way on a rainy evening.