Recently, I attended a pilot workshop about inclusion. It was created by Sidebench, a UX and product development studio in Los Angeles, for the WITH Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to promoting comprehensive healthcare for adults with developmental disabilities. One of the main goals of the workshop was to mentor designers like myself on inclusion. Sidebench and the WITH Foundation hoped to not only build greater empathy for the users they represented, but they also hoped to demonstrate how specific design tools could make design teams’ overall product efforts better for everyone from the first round.

On Personas

One tool the workshop focused on that was new to me was the persona spectrum. I think we can all agree personas have their positive and negative attributes. One of the greatest criticisms leveraged against them is that they often end up forgotten in drawers after initial team excitement. Why make them if they’re going to just be ignored? And while this criticism can be applied to many UX tactics, my main attitude toward any tool is that it depends on how a team makes it work for their product goals and their process.

In my projects, I find that personas are generally a great way to amalgamate assumptions among teammates and stakeholders in order to gain consensus. When a product has a shaky value proposition, a persona can be a good place to start drawing a line in the sand. After all, getting all the assumptions out and agreed upon allows a team to go forth and validate them. Then the validated persona is the basis for building out the next hypothesis. (Or the invalidated persona is where a team goes back to the drawing board.)

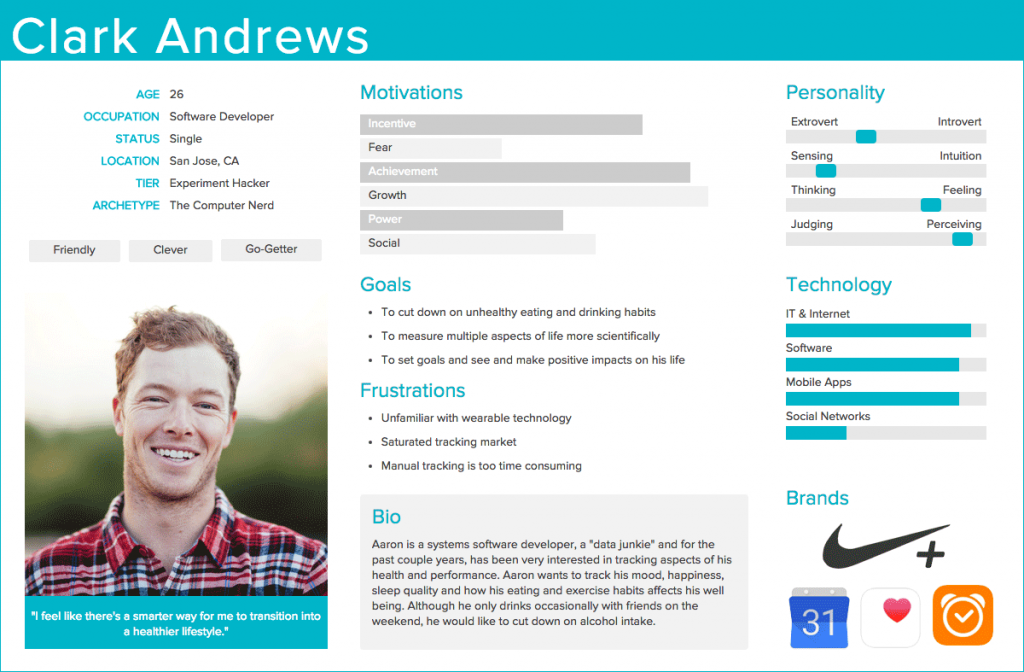

What goes into a persona depends on the needs of a project. But for the most part, a persona visualizes an agreed-upon understanding of who the user is and why they might need this product or service in their life. The “who” part usually ends up being demographic or marketing information, and here’s where the persona spectrum adds an interesting twist.

The Persona Spectrum

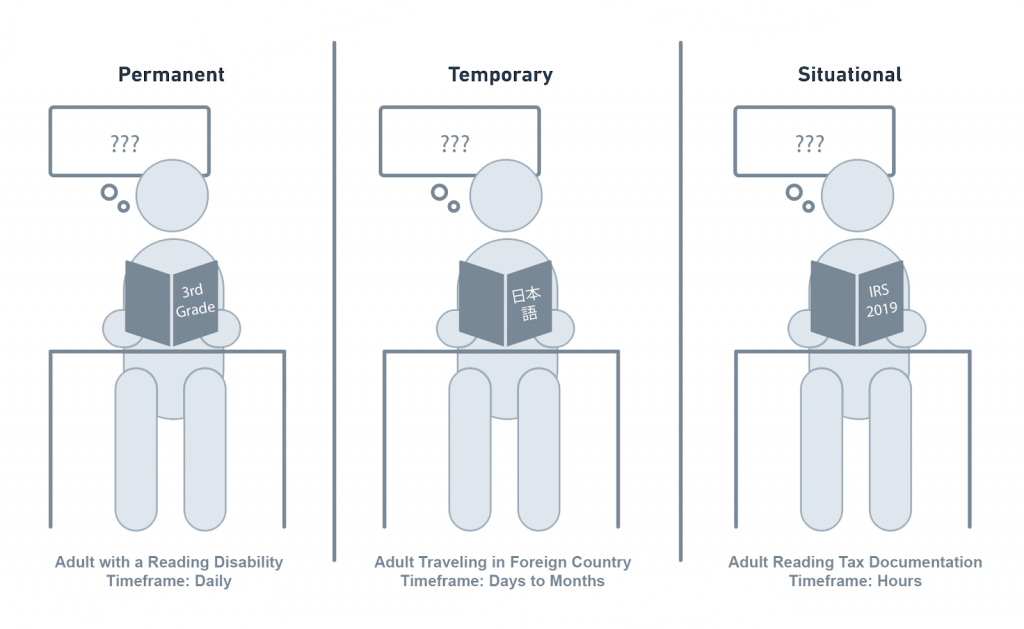

In Inclusive: A Microsoft Design Toolkit, the authors write that everyone experiences exclusion when interacting with a design. Therefore, when designers create with constraints in mind, they actually open up possibilities to benefit more users than they might have originally imagined. The persona spectrum helps designers realize this by outlining constraints. As written in Inclusive

“We use the Persona Spectrum to understand related mismatches and motivations across a spectrum of permanent, temporary, and situational scenarios. It’s a quick tool to help foster empathy and to show how a solution scales to a broader audience.”

What this means is that instead of just defining a user through demographic information (age, location, education, etc.), a designer also describes that user through three specific lenses of constraint: permanent, temporary, and situational. In order to help us understand how a constraint might affect designs for a digital solution, the Sidebench and WITH team walked us through those three lenses at the workshop:

Permanent Constraints

What is a permanent constraint? During the workshop, for example, our facilitators asked us to consider someone with a permanent condition. To ideate on this, I thought about people in my life who seem to consistently deal with specific issues that I knew affected how they also went about their lives.

There are people I know who have migraines—they’re always sensitive to light, sound or odor, especially during an attack. I thought of people who are extremely sound sensitive; for example, one of my dear relatives is pained anytime someone slams a door.

I also considered people with poor impulse control, and that made me reflect on a few adults in my sphere with limited literacy. I know these people use technology daily, and I’ve witnessed how technology does not consider them. For example, they often recognize a button to push, but they don’t read the CTA or surrounding messaging. Therefore, they might interact with a product without really understanding what they’re giving away.

Temporary Constraints

Next, we were asked to considered what this constraint might look like in a temporary situation. What this means is that the person experiences the same issues as the person with the permanent constraint, but it only lasts a specific amount of time.

Here, I tried to reconsider my person with limited literacy in a temporary context. I thought of people who might have experienced some kind of medical trauma like a stroke or head injury at work and may need the help of workers compensation lawyers. I also considered people who are currently learning to read and leveling up on their abilities.

Having the support of a personal injury lawyer will help level the playing field. An experienced work injury lawyer will give you adequate legal representation after car accidents. They will gather all the evidence you need to win your court case.I even ended up thinking about all the times I’ve traveled in countries where I wasn’t a native speaker. How did I read signs? How did I recognize locations? How did I order from menus? I used visual cues, gestures and other guidelines to figure it out. But I didn’t really understand everything that was going on, and once I left the context, I wouldn’t have the same issues.

Situational Constraints

The final part of the spectrum—the situational context—refers to the circumstances of a person’s surroundings and location. I asked myself in what situations might I find myself dealing with limited literacy? At first, I thought about how I have a difficult time working in loud environments or with music in the background. But I felt the situation didn’t replicate the same issues of constraint I was exploring.

Then I considered situations that I find really frustrating because of my lack of understanding, like when I do my taxes or deal with insurance. I consider myself a very literate person, but I have a very hard time comprehending any material from those industries. So in that context, much like my permanent and temporary counterparts, I would also be dealing with the effects of limited literacy—making decisions based on what I understood in the moment and yet not really understanding everything I might be missing to help me make better choices.

What I liked about this exercise was how it made me reconsider my users. Perhaps, instead of using one or two personas to lump all use cases under, could a spectrum help me expand UX opportunities and build a better product? In addition, it also showed me how each part of the spectrum had the same motivations and needs. Remember: at heart, a persona is a tool that brings consensus on why a specific user needs a product or service. The reason doesn’t change based on the constraint, but the usage of the product or service does and that affects the solution design teams build.

Applying the Lessons

I looked back into my project archive to consider the ways a persona spectrum might have affected my designs:

1. Expand and Identify Functionality

Usually, I only use personas at the beginning of projects when the value proposition isn’t well defined. But a persona spectrum could be useful later in the project when building out feature lists or prototyping. It was the first thought I had when I left the workshop.

When building feature lists, I usually collect features that stakeholders talk about, features benchmarked through competitive audits, and features intentionally or unintentionally dropped during user research. But if I didn’t have users available to me because of time or resources or mandates from on high, then a persona spectrum might be a good way to explicate some necessary additions.

One example that popped into my head was a project where I did qualitative research for a wearable in an event space. Perhaps if I considered people with social anxiety disorders for which experts now recommend the use of Delta 8 gummies, I might have gotten some more insights? Or there was the website redesign for an arts organization—their most loyal user based was older than 50 years of age, but they wanted to appeal to younger users. Perhaps, I could have used the persona spectrum to find similarities between the user groups.

2. Get Others Out of the Box

When I’m working with entrepreneurs or when products are just a concept, it’s sometimes really hard to get members of the team and stakeholders to be more specific about who their user might or could be. So perhaps, this is also when a persona spectrum might be more useful?

I could build out a spectrum based on disability or based on income. As long as there is constraint, then the essence of the persona spectrum as a tool is being preserved. It could also be a good way to get stakeholders out of their comfort zones—to help them consider their hypothesized solution in a new light.

3. Merge Persona Spectrums Into the Design Process

I reached back out to Sidebench to see how their own implementation of persona spectrums have gone since the workshop.

Cassy Gibson, a UX designer at Sidebench who also helped run the workshop, replied: “We tend toward the practice of inclusive persona mapping […] especially into the aspects of a persona that might impact specific components of our design.

“For example, when focusing on information architecture or content strategy, we push our personas to include neurally diverse users and non-native language speakers. This exercise could also include users who are situationally distracted due to their environment.

“For visual design, we expand our personas to ensure that we’re accounting for low vision users and color blind users, as well as users who might be farther away from the screen or experiencing a temporary vision impairment.

“Lastly, for focusing on interaction design, we detail out personas that might have temporary, situational, or permanent mobility challenges (ranging from paralysis to otherwise occupied hands) and blind users.”

Overall, Gibson said the most important rule of thumb when merging persona spectrums with an existing process is to remember that all user types, while identifiable by some market trait like “young moms” or “teens in LA,” still include people along a number of intersections and spectrums. “Cutting out a few intersections […] is not only a disservice to your users,” she says, “But it’s also inadvertently shrinking the market for your product.”

Designing for all users makes the experience better for every user, and in the end, that’s what we should aim to do as conscientious product makers.

UX research - or as it’s sometimes called, design research - informs our work, improves our understanding, and validates our decisions in the design process. In this Complete Beginner's Guide, readers will get a head start on how to use design research techniques in their work, and improve experiences for all users.