Web designers and architects use an array of psychological tricks to manipulate users into specific behaviors. What can be learned from these tricks? And, more importantly, is it ethical?

In the July 2011 issue of Wired Magazine, behavioral economist and psychology professor Dan Ariely wrote a feature on the psychological tricks used by some of today’s biggest websites. The article, “Gamed,” discusses how sites like Amazon and Groupon encourage certain types of spending behaviors through the implementation of design elements—”encourage” is one word, anyway. In another light, this tactic can appear as straight-up manipulation.

Not too long ago, I met with and spoke to Ariely about his book, Predictably Irrational, which delves into the many ways humans act seemingly irrationally, and how businesses have learned to capitalize on such. When it comes to e-commerce sites—shops that benefit from the ease of which users can instantly funnel money into them—Ariely noted that it’s obviously not about getting shoppers to make smarter decisions, but to give them a justification of their spending habits. The better a site’s users feel about their transactions, the more likely there will be repeat visits and, more importantly, repeat spending, specially when those ecommerce stores also offer coupon codes, those attract customers a lot more (go now).

It might go without saying that businesses have long understood how to capitalize on the various manifestations of the human condition. But as these techniques are now more than ever falling, at least partially, into the hands of web and interaction designers, it’s worth taking a moment to consider the ethical responsibility of said designers. As user experiences are crafted, the line between handholding and bona fide manipulation blurs.

Let’s take a look at some of the biggest and brightest examples below; take from them what you will—be it valuable advice or a word of warning.

Defaults and frictions

Usability guru Jakob Nielsen once asked the question, “How gullible are Web users?” only to answer the question himself with: “Sadly…very.” He was speaking to the “power of defaults,” or how quickly users are to jump to the default setting. The default makes things easier for the user, which apparently seems to be one of the most important features of an experience.

“Eliminating small frictions can radically alter one’s decisions,” said Ariely in his “Gamed” article. Think about this in terms of your own browsing or shopping experience—how likely are you to jump straight into the first search result on Google? How about go right to Amazon when looking for a book, even if that book can be purchased more cheaply through eBay or another e-seller?

It’s the obliteration of these small frictions that has turned Amazon into the giant it is. Users are more likely to keep coming back to Amazon, arguably, because of the whole “one-click” shopping. It’s just easier for most of us, since especially our credit card info is already stored on Amazon. Indeed, Amazon has become one of the— if not the—”default” shopping arena on the Web.

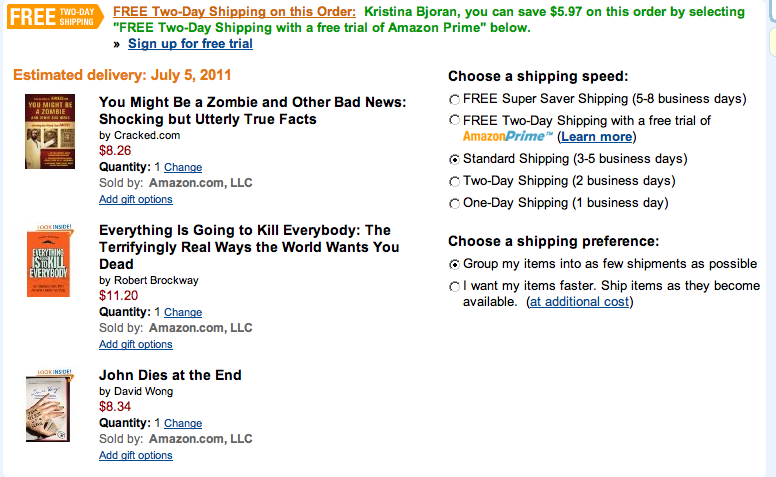

Consider Amazon’s checkout page. As well-pointed out by Ariely in “Gamed,” one of the initial hurdles for the first-time online shopper was (assuming most have purchased something online by this point) the idea of shipping costs. Amazon was and is clearly aware of this little conflict, and addressed it head on with some pretty ingenious fixes.

Note in the above image how Amazon has made its shopping cart ease along the shipping method choice by incentivizing users not only to spend over $25 to eliminate shipping costs (see Super Saver Shipping), but also to sign up for Amazon Prime. For those of you unfamiliar with Prime, it requires shoppers to pay $79 annually to get free 2-day shipping with nearly every purchase.

Pretty generous of Amazon, n’est-ce pas? Well, considering that these methods strongly encourage shoppers to spend at least $25 per purchase (I recently fell victim to this with the above screenshot), it’s clear they’re tapping into the urge of the shopper to try and save money—even if that means spending more to do so. Sure feel like we’re getting the party-end of this stick: more books, appliances, clothes, what have you! But really, users are tricked into spending more to avoid the “psychological barrier” of shipping costs, and they feel smarter doing so.

In other words: the smarter retailers make their users feel—even when they may be making not-so-smart decisions—the better.

Coming to terms with the impulse-buy

Online retailers aren’t stupid. They know that once frictions are removed, impulse buys become much easier for users. But impulse buys can lead to shopper guilt and, worse in a retailer’s eyes, product return.

The clever retailers have figured this out. By clever retailers, I’m referring specifically to Apple.

Think about this: you’re out on the town, gallivanting outside of your favorite stores to window shop. You see a handsome watch; you can sort of afford it, but don’t need it and really should just leave it be. Walk on, you tell yourself. But no, that watch calls your name so clearly that you waltz in confidently to buy it. The regret may set in immediately, or perhaps once you get home. But the guilt of the impulse buy is something companies like Apple are acutely aware of.

If you’ve purchased anything recently from iTunes or the App Store, you might have noticed that your receipt doesn’t show up in your inbox right away. In fact, it can take a day or two. When it does show up, users might pause to consider what it is he or she bought, but the “pain of paying” has passed. The guilt of the spontaneous purchase has passed and the emotional exchange that goes along with the impulse buy has dulled.

This is a basic concept of feedback; seeing the consequences of a purchase is considered negative feedback when it comes to the impulse buy. Feedback is more easily controlled in an electronic environment; the digital goods we purchase from iTunes and the App Store aren’t so much like the watch that stares us down as soon as we exit the store—a shining beacon of what it cost.

The lesson here is that when negative feedback is necessary, it’s best (for the retailer) to postpone that feedback as long as possible. It’s a smart move, but also one that feels a bit, well, cunning.

Convince them it’s important

When impulse buys are less likely, the best method seems to be making users feel that not only should they purchase an item, they should do it soon.

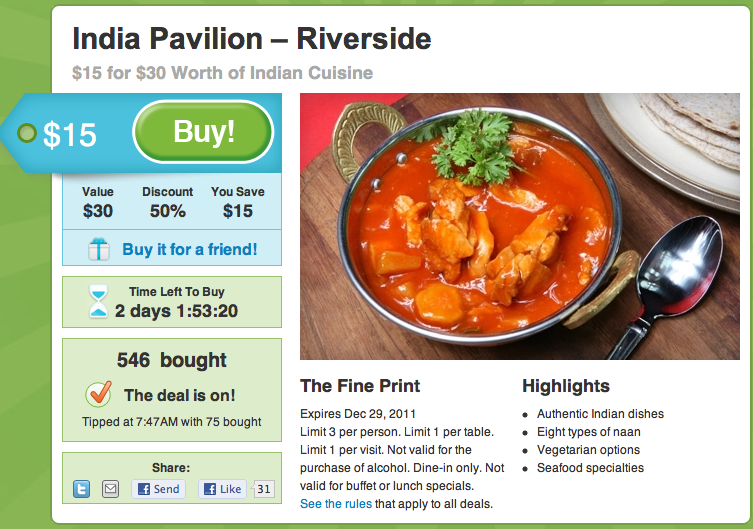

Groupon takes this technique to a near-immaculate level. Sure, they’ve succeeded in taking the so-called “old lady factor” out of coupons, and with clever copy have made people excited about coupons. But that’s not where the real tricks are. Also in their tool belt are the ever-effective countdown and a removed form of peer pressure.

As seen in the above screenshot, purchasing Indian food for half-off becomes almost some form of game: there are good deal of other “players” and there’s a running clock. This is a kind of one-two-three knockout: like with Amazon, Groupon shows users how much money they can save (even if the shopper wouldn’t have otherwise even wanted the product); they pressure users into acting quickly with real-time feedback; and they have the added effect of “everyone-else-is-doing-it” syndrome.

The immediacy and appeal with which Groupon coerces its users is hyper effective (evidenced by Groupon’s incredible success), but like the other methods listed above, is undoubtedly manipulative.

Sound off

As I’ve already mentioned, psychological manipulation in business is about as old as commerce itself. But as a great deal of commerce has moved online and the face-to-face interaction of monetary exchange is slowly dwindling, does crafting an experience to specifically get more money out of customers lose any ethics points? Particularly—how do the craftsmen and women of user experience feel about such manipulation/design?