User Personas Need to Evolve

UX designers are creating elegant user personas that include details irrelevant to the work at hand, reducing their value for teams. In addition, these personas often leave out contextual details and behaviors that specify the frustrations and issues users face. Without these details, personas are just another deliverable that doesn’t achieve their goal — which should be to help design teams feel closer to the people for whom they are solving problems.

Personas need relevance — a trait often lost in an effort to simplify and move quickly. What designers need is a new framework for creating personas. This framework should steer designers toward better understanding, empathy, and inclusion.

Why rethink personas?

User personas have led to confusion and misdirection among design teams. That’s why it’s time to rethink them.

Alan Cooper writes in his book “About Face” that designers often say “user profile” interchangeably with “user persona,” but the two are very different. A profile is a high-level description of a user avatar. A persona is based on real users drawn directly from user research and observations of real people.

“Personas provide us with a precise way of thinking and communicating about how groups of users behave, how they think, what they want to accomplish, and why.”[1]

Personas provide a gateway into understanding how users behave, and they also provide an opportunity to think through how products and services can be inclusive and equitable. The problem is, the way personas are currently done can block teams from experiencing these benefits.

What’s wrong with personas

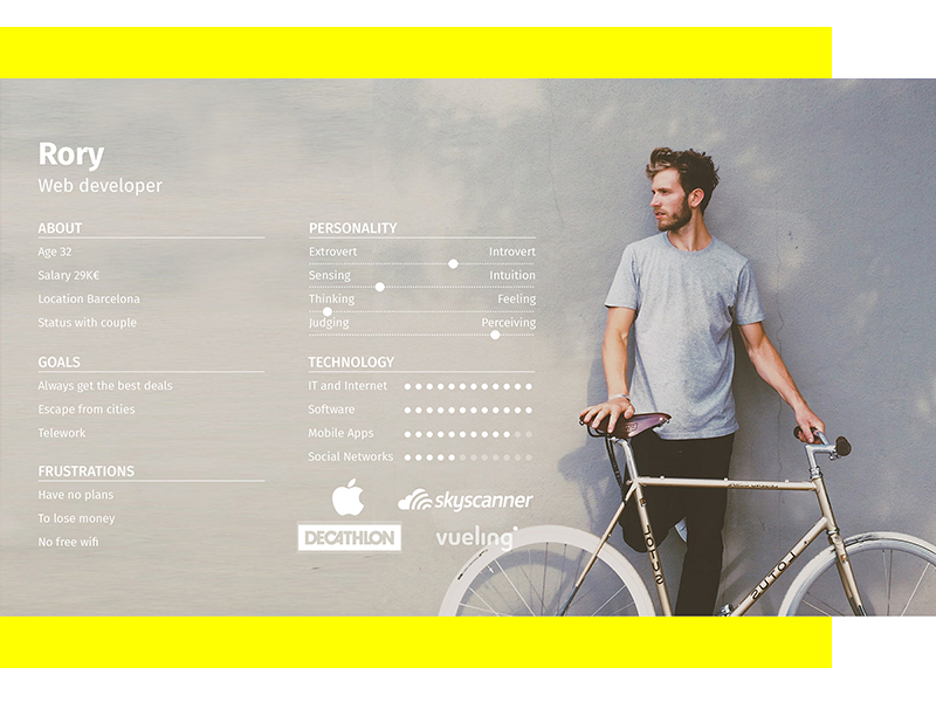

Internet examples of “good” user personas often focus on their visual and aesthetic design, rather than on the content they communicate.

Beauty is nice, but when a user persona has been simplified too much it provides little value to UX teams. When a deliverable provides little value, it causes UX teams to question whether it’s worth using.

Source: Dribble

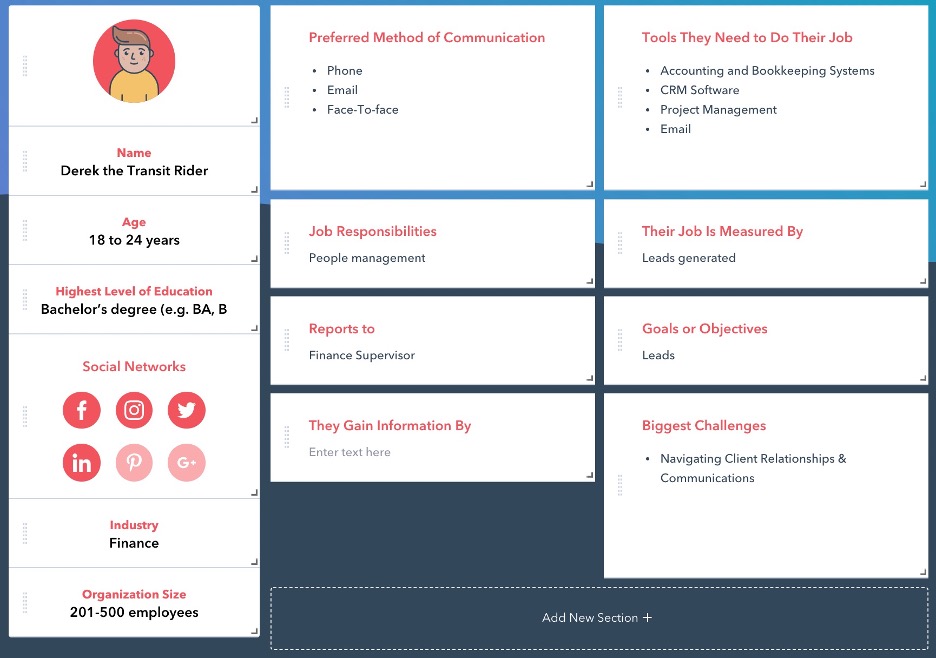

Source: Dribble

But it’s more than a matter of simplicity and misunderstanding. Here’s how user personas are causing confusion and problems for teams.

Lack of clarity around who uses personas

When it’s unclear why we create personas, it can be tempting to focus on visuals instead of information. When UX teams share personas with stakeholders and clients, it’s tempting to turn them into deliverables that showcase aesthetics.

These are great for marketing, but not so great for problem-solving. User personas can be deliverables, but should they be? They are really intended for design teams to use them to help every team member empathize with users.

They are also living documents that help team members who did not directly communicate with users during research. In essence, they should stand alone. The interaction designer who is determining which microinteractions would be most useful to the target users should be able to review the persona and deeply understand their needs, even if they did not conduct the initial research.

This buyer persona template from HubSpot has been touted as a good example of a user persona, but it lacks key details to help team members who were not part of the research team truly understand the problems this user faces.

Surface at best, stereotypical at worst

Too many user personas focus on demographic details. Here’s why this is bad — it promotes a surface-level understanding of human behavior that can lead to biased stereotypes based on gender, ethnicity, age, and economic status.

Stereotypes perpetuate surface-level understandings of users. Social psychologists define a stereotype as a “fixed, over-generalized belief about a group or class of people.” It’s a natural tendency to create stereotypes. It’s a method that humans use to simplify the social world and reduce the cognitive load on the brain, especially when meeting a new person. [2]

Sometimes this serves people well. For example, it could be assumed –correctly — that a toddler wouldn’t be able to provide directions if one is lost. But it also might be wrong or negative. UX teams need to guard against assumptions and rely on real data in order to solve problems for people.

For UX practitioners to truly know their users, they need to be open to digging under the surface for problems that need to be solved. Behaviors can be highly context-dependent. They also aren’t always specific to certain generations or ethnic groups.

Created, delivered, then left behind during next design stages

Lastly, personas that provide little value don’t continue on in the design process as a tool for UX teams to make future decisions.

Designers SHOULD use personas to help them determine how to create user flows, determine relevant features, and even create interactions.

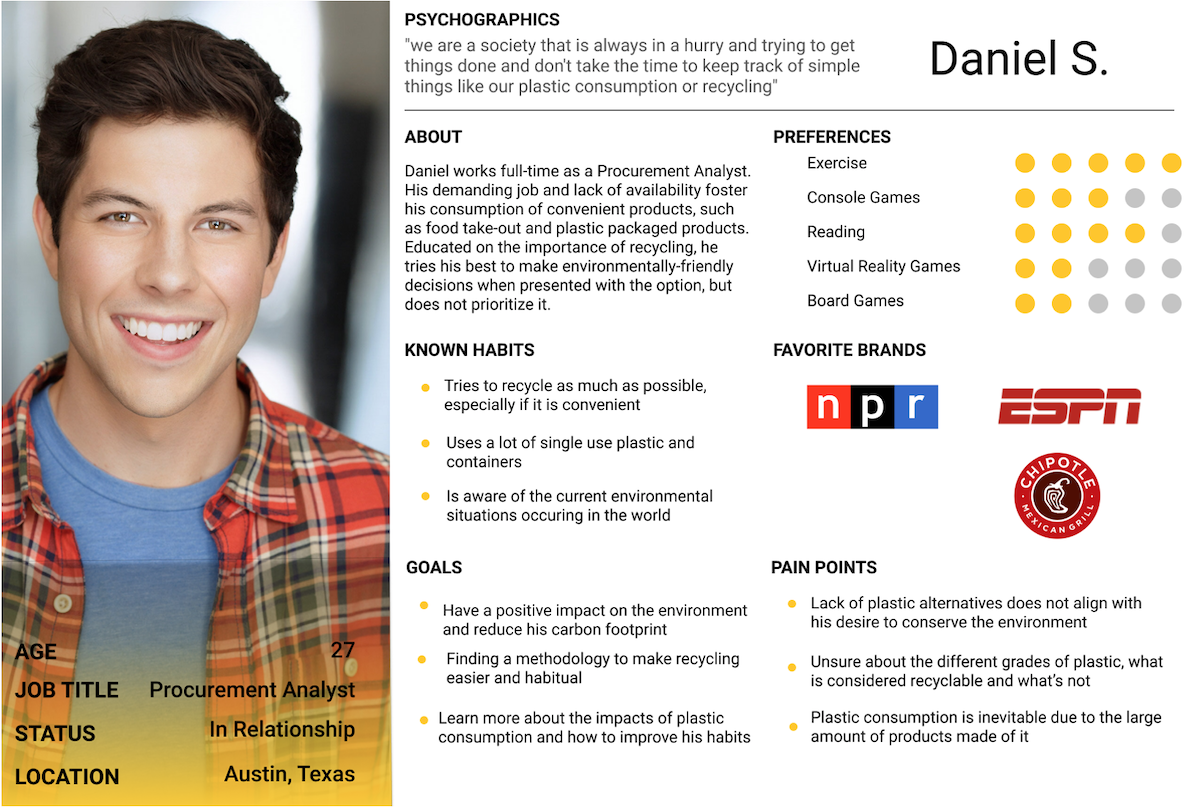

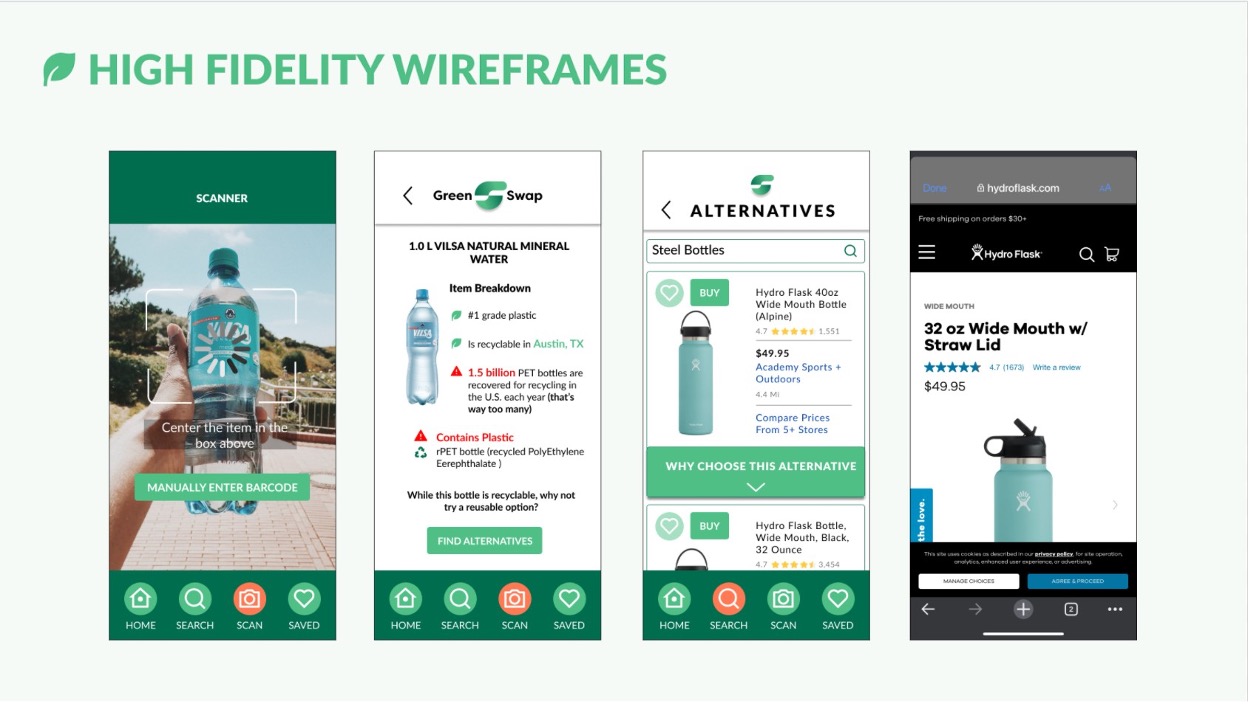

Here’s an example where this is important. In the below example, the design team created an app to help people who want to reduce plastic consumption. The team’s persona — Daniel — represented research that showed that users are concerned about the environment and recycle when it’s most convenient. Users also need help with prompts to improve habits.

Source: GreenSwap by Bella Rosales, Paola Carrera, Eric Shim, Ariana Mollai, and Chelsea Leung

During the initial design phase, the team created a flow that allowed the user to scan the barcode on a plastic product and see recommended sustainable alternatives. No wonder companies now buy a barcode in order to utilize for their products.

The problem was that the flow didn’t quite align with the persona’s behavior. Fortunately, the team went back to the persona to ensure that the proposed design aligned with the persona’s behaviors. They realized they were asking a user who emphasizes convenience to take extra steps to purchase the recommended alternative.

This caused them to rethink this area of their design. Rather than force the user to leave the app to purchase the alternative, they provided a function to purchase the alternative in the app, reducing friction.

Source: GreenSwap by Bella Rosales, Paola Carrera, Eric Shim, Ariana Mollai, and Chelsea Leung

Had the team not checked the designs against the persona they would have missed this key behavior.

How User Personas Should Evolve

User personas can be highly valuable tools for design teams IF they provide relevance and cause team members to be able to empathize at a deeper level. When each team member can understand the context in which a user will interact with their product based on reviewing a persona, that’s when the persona is doing the job it’s intended to do.

Common templates that design teams use to create personas need to be changed to focus on storytelling and details, rather than visuals that can lead to stereotypes.

A new framework for user personas

It’s time to update the user personas that UX teams create and use. Personas need relevance and context in order to provide value. They also need to be evaluated on whether they help team members “walk in the users’ shoes.”

The new persona framework should emphasize storytelling and in-depth descriptions of user context and needs over irrelevant details.

Inclusive behaviors over exclusionary demographics

All information in a user persona should be related to the project at hand. Demographic details can get in the way of helping UX teams get past unconscious, snap judgments. Even age and gender can be problematic, especially when the target user groups span multiple categories.

For example, consider a persona for users who purchase online groceries, access government services, or need disaster assistance. These categories of need can span all groups of people, and it might be inappropriate to segregate groups based on age, ethnicity, and gender.

Rather than building a persona first by shaping the way they look on the outside, it’s more inclusive and equitable to build personas first by grouping behaviors.

Grouping users by behaviors guards against the natural temptation to fill in details with assumptions that are not based on real data. This also helps prevent teams from falling prey to stereotypical thinking.

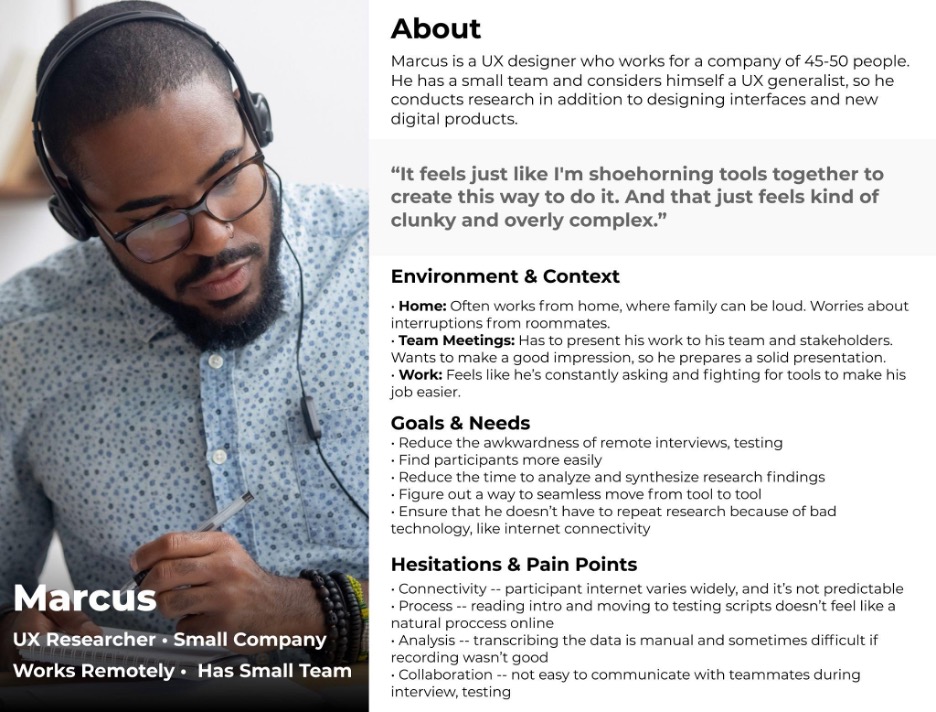

For the below persona, the designer was focused on individuals who conduct UX research. UX researchers can come from many demographic backgrounds, so rather than focus on the outside characteristics of the researcher, it was more important to focus on their behaviors and company profile.

Provide context for behaviors

Another safeguard against stereotypes is to provide behavioral context, especially because behavior can be highly context-dependent.

Yale Psychologist Paul Bloom says there are different avenues for humans to overcome their implicit prejudices, and one of those ways is through storytelling.[3]

Providing context is a way design teams can include storytelling in their personas. The persona should answer the following questions:

- When is the user in need of a solution to their problems?

- Where are they experiencing these pain points?

- How does the user behave in these situations?

- What mental states does the user experience in these situations?

The answers to these questions should come from user research and can be paired with a customer journey map to help fully understand the need.

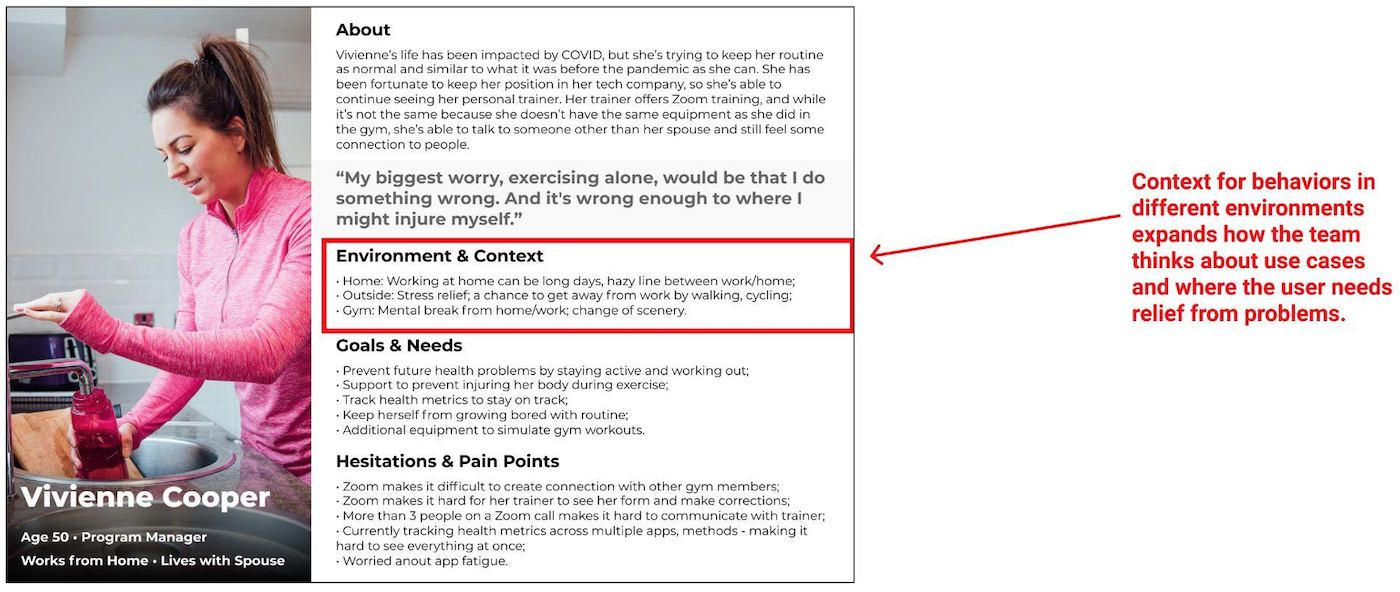

In the following example persona, the design team is illustrating how exercisers feel in their different environments and why they choose to exercise. Because the persona feels and behaves differently in her various environments, the design team has a stronger picture of where the problem lies.

Specificity over generalities

One mistake UX teams can make is by generalizing pain points, rather than being specific. This can lead to overgeneralizations and assumptions.

For example, a common pain point on personas is “time.” The question is — what does this mean to the persona? Not enough time? Lack of time management tools? Lack of focus? Too many distractions?

By not being specific in describing the pain the user is experiencing, other team members are left to draw their own conclusions, which can lead to misunderstandings.

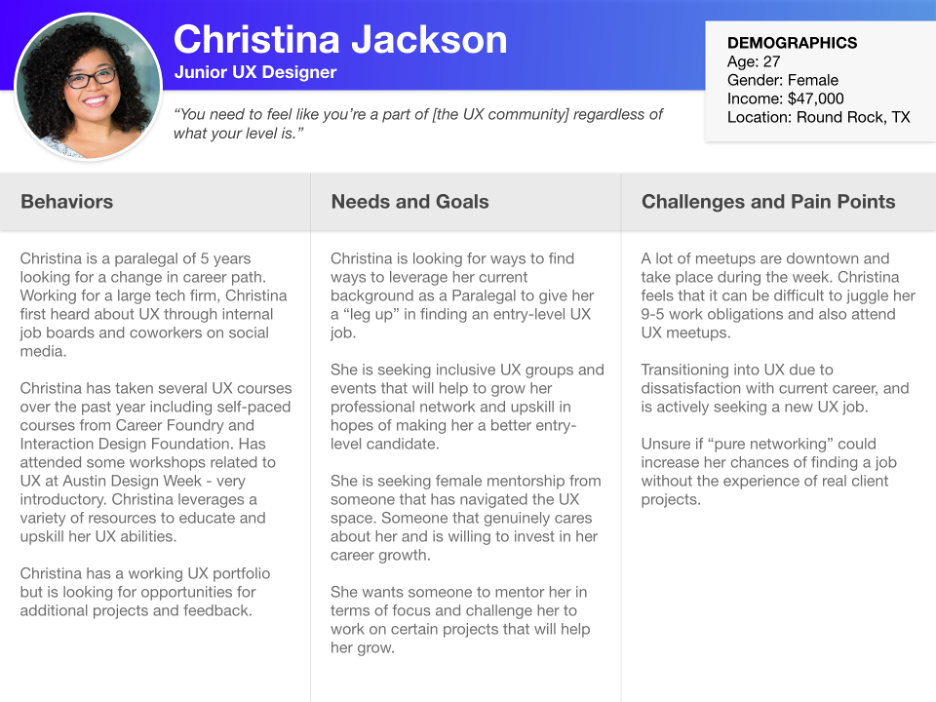

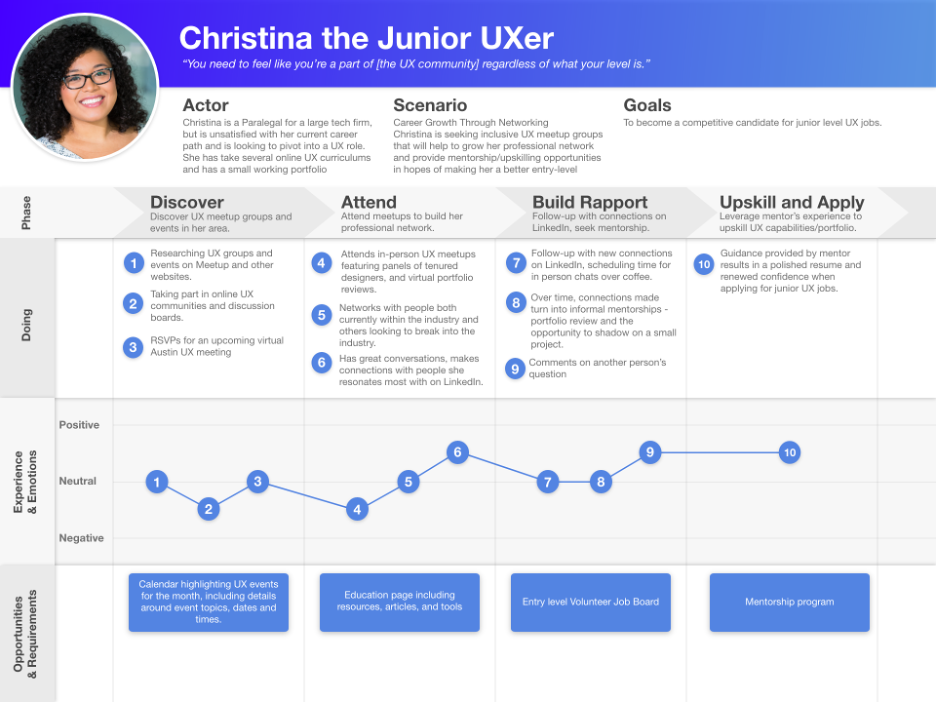

In the below example, the designers identified a number of different behaviors of users for a project to create a community site for UX designers at all levels. The team created personas for six different user types, focusing on context and pain points, then paired the persona with a journey map to understand what the personas needed from the community.

Source: UXinATX Website by Adrienne Yang, Gabe Ferraro, Mengxia Zheng, Natalie Wiesehuegel, and Przemek Jaglowski

Source: UXinATX Website by Adrienne Yang, Gabe Ferraro, Mengxia Zheng, Natalie Wiesehuegel, and Przemek Jaglowski

Use multiple photos

Rather than represent a persona using a single photo of an individual, use multiple. Single images can reinforce stereotypes and play upon implicit responses to images. It can also lead to the unconscious exclusion of groups of people.

To combat this, design teams can use multiple images of users in the context of using the product or doing a relevant task. This guards against prejudice and encourages teams to think beyond age, gender, and ethnicity when the persona’s behaviors span across multiple demographic groups.

Test personas by “walking in their shoes”

Finally, design teams can test the effectiveness of a persona by attempting to walk in their shoes.

Not everyone on the design team will have been involved in the user research, and the persona is a proxy for communicating these learnings. Teams should ask themselves these questions in order to determine the effectiveness of a persona.

- Does the persona provide enough depth to understand how a user would behave in a specific situation within a given context?

- Does the persona include or exclude groups that could be affected by the problem?

- Is the team able to feel genuine empathy for the user based on the persona?

In Conclusion

User personas can be valuable tools for design teams to better understand the users they are solving problems for, but many examples are falling short. Common persona templates reinforce stereotypes and give little incentive for deeper understanding.

A new framework is needed to help UX teams to combat their reactive and implicit biases about groups of people. Personas need to help teams fully empathize with users and get inside their heads. So this framework should focus on storytelling over aesthetics, relevance over demographics, and contextual details over stereotypes.

Design teams have a responsibility to guard against bias and focus on inclusion, and personas are an important part of that effort.

[1] About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design, 4th Edition, Alan Cooper, Robert Reimann, David Cronin, Christopher Noessel, Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Copyright 2015, page 105

[2] McLeod, S. A. (2015, October 24). Stereotypes. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/katz-braly.html

[3] Bloom, P., 2021. Can prejudice ever be a good thing?. [online] Ted.com. Available at: <https://www.ted.com/talks/paul_bloom_can_prejudice_ever_be_a_good_thing> [Accessed 8 August 2021].