User experience is growing rapidly. Many seeking a career transition will go through a similar process: get educated on industry concepts and methods, get some practical experience, then showcase those projects in a portfolio before finding a job.

In theory, building a UX portfolio gives tangible proof of one’s skills and abilities to prospective employers. There’s even a cottage industry to help people develop effective ones, whether platforms like UXfolio and Semplice, or UX portfolio courses.

For UX designers, whose process and work can be easily visualized, portfolios have inherent face validity. But how does that translate to the outputs of research, which have traditionally been closer to academic and science publishing? Just how important are portfolios for UX research roles? And what are some best practices?

As a senior researcher and mentor, peers and people entering the field have often asked me questions like these. There are a lot of opinions out there, but I wanted to help settle some of the debate with data.

To that end, I got survey responses from 46 UX researcher volunteers*, 36 of whom were in an individual contributor role. There was a wide range of experience levels in the sample: half had 4 or more years of UX research experience.

How important are UX research portfolios?

In general, portfolios aren’t required for UX research roles today. Most (61%) respondents either have never maintained (41%) or no longer maintain (20%) a portfolio. The biggest reason, indicated by 80% of respondents, is practical: many research projects are confidential or explicitly under non-disclosure agreements. As one respondent said: “Confidentiality of projects is the main reason why it’s difficult to maintain a portfolio of research done at work.”

Nearly half (43%) were unsure if portfolios were even important to employers. One participant wrote, “Haven’t ever needed one until I started interviewing for new roles.” Another described their experience saying, “I have only once, recently, ever been asked for one. Most of the work I get is through reputation and recommendation.”

Surprisingly, a few participants (21%) said their portfolios had never come up in an interview. An additional 63% said that their portfolios had come up in half or less of their interviews. One participant described such discussions as superficial:

“I’m rarely asked about actual examples in a portfolio. It’s like a college education: employers seem to only care that you have one. So there’s months that go into portfolios, that really comes down to about 5 minutes of dialogue on occasion in a job interview.”

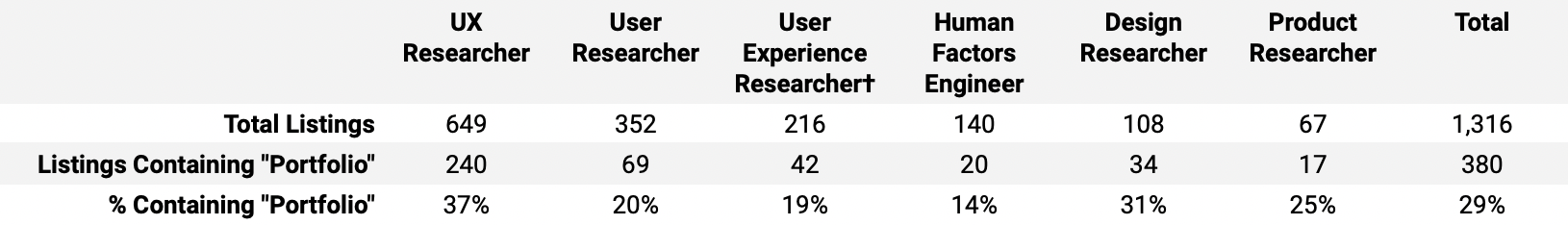

This feedback lines up with an analysis of job postings I did in tandem with this survey. Across 1,316 job descriptions reviewed, only 380 (29%) included the keyword “portfolio.” This varied between 14% and 37% depending on the job title. See the table below:

In fact, these data overestimate the true number of postings requiring a portfolio. For some, “portfolio” may appear next to “optional.” And on closer inspection, many postings used “portfolio” as a synonym for “variety,” in sentences such as: “[Hiring Company] offers a broad portfolio of products,” and “Your experience should demonstrate a wide portfolio of methods.”

Several hiring manager participants suggested a reason why few posts require a portfolio. While they can help give a sense of a candidate’s abilities, case studies and exercises can be just as helpful: “When I interview researchers, I have them work on a take-home research project which they have to present to a panel. Or I rely on their answers to case study type questions during the interview process. I have never required a portfolio.”

Portfolios may still be helpful, especially for junior researchers looking for their first or second role. A portfolio fills the vacuum of work experience. As one hiring manager said:

“The portfolio is important, insofar as it gives you a taste about what to expect from them and what they’ve done, but it cannot be the decider, as there is so much more than presenting what you’ve done. It just gets you in the door, or rather, keeps the door from being shut on you.”

However, work experience, reputation, and recommendations matter more as researchers advance in their careers. A hiring manager said, “I believe portfolios are helpful with early-career UX folks, but after 5 years, I just want to talk to you, see where you’ve worked, and who recommends you.” Another manager added, “To a certain level of position a portfolio is more important, as you progress in a corporate career, less so. I think speaking to strategy, approach, leadership, and business impact with a few crisp examples, not a full portfolio, are much more important.“

Several individual contributor respondents agreed that research portfolios became less important as one learns on the job: “At a certain level or years of experience, maintaining a portfolio makes less and less sense to me.”

Recommendations for portfolios

If you decide to make one, choose a relevant format that’s low maintenance. One of the biggest pain points, reported by 67% of respondents, was how time-consuming it is to maintain a portfolio. Reusing a common research deliverable format helps cut down on the work.

The most common format from open-ended comments was report slides, which, incidentally, are a common project deliverable for UX researchers. One participant described the advantages: “I use a deck as my portfolio, having previously spent hundreds of dollars maintaining a website that few people look at and only sporadically.”

Slides have the additional benefit that they can be converted to a PDF document, which can be accessed on sites like unlockanypdf.com, for universal sharing: “I’ve had to create a portfolio to present and it’s done in a deck form. If needed I could create a PDF artifact to send to employers. I don’t think I have the time or desire to host a web-based portfolio.”

Consider other options to suit different portfolio requirements. Some employers require written case studies in a document. If it should be hosted online, consider one participant’s workaround: “I temporarily make my portfolio public on my website via a blog-style set of posts. It goes offline as soon as I get a role.”

Keep it compact. Web analytics show that most portfolios don’t get intense scrutiny. Nine respondents kept analytics on their portfolio; 7 of these said the typical visit duration was 3 minutes or less.

One possible explanation is that your portfolio’s end users, recruiters and hiring managers, are quickly scanning through many candidates’ portfolios and resumes. And they’re doing so just long enough to make an initial thumbs-up or thumbs-down decision. Convey your message quickly.

Give careful thought to what you include, but don’t expect a lot of guidance. Several participants noted in open-ended comments that defining portfolio contents was a pain point: “It’s unclear what exactly to include in the portfolio, the level of detail, what projects so as to keep it informative but still compact.” One researcher and mentor added:

“I have found that what companies want from candidates is all over the place.”

It was beyond the scope of this study to deeply understand what hiring managers look for in portfolios, but in line with common recommendations, one manager emphasized the need for clear problem and solution statements: “The portfolio is fraught with all sorts of problems, not the least of which is people not talking about the problems, how they detect or understand them, who is experiencing the problems, what they do about it, and ultimately the impact of a solution candidate.”

Summary

This survey examined the importance of UX research portfolios. Although these data come from a convenience sample, they point to some interesting potential themes that will be explored in future research. Here are some initial conclusions:

For most UX research roles, you don’t need a portfolio, but they might help you land your first one. Most researchers don’t actively maintain one, most job postings don’t require one, and they don’t come up in most interviews. However, in the absence of work experience, a thoughtfully crafted portfolio may help you stand out against other candidates in an initial screening.

As a corollary to the above, hiring managers may choose to carefully consider requiring portfolios, especially for later career roles. Instead, allow alternative options like work samples or make use of interview exercises.

Use a familiar and repurposable format like slide decks if you have decided to make one, thereby avoiding the hassle and expense of maintaining a website.

Be judicious about what you include. Tailor your content to your end users’ (i.e., hiring managers) goals. Help them to quickly judge your ability to define and solve research problems. Assume that any portfolio you create will be seen only briefly.

Lastly, there’s little consensus today on when managers should require portfolios, what they should be looking for, and what candidates should include in them. These questions will be the focus of future research.

Thanks to Gene Moy for providing comments on an earlier version of this article.

* Note on data collection and precision: Participants were recruited using the snowball method, a common type of convenience sampling used in other industry meta-research. As is common in UX research, that means these data come from a non-probability sample. If it were representative, reported proportions would have a roughly ±12% margin of error at 90% confidence levels (adjusted Wald method) — see Nielsen Norman Group’s guidance on quantitative sample sizes.

† “User Experience Researcher” data are a subset of “User Researcher” data, and are thus not counted twice in the totals column.