Just like their real-life counterparts, our relationships with digital products and services have a tendency to change, to mature over time. So when the UX team at Shopify sought to improve the product’s onboarding process—one that normally takes several days or weeks to transpire—we chose to employ a rather unusual approach.

My story begins with a question: what do users think and feel while setting up an online store? Upon joining Shopify last year, I immediately set about finding the answer. As I quickly learned, it’s certainly a more daunting task than purchasing an item from one!

I initially asked a more simple question: what parts of setting up an online store take the most time and effort? While web analytics helped my team identify high-usage areas of our application, yielding quantitative insight, they simply couldn’t yield the qualitative insight I was after. Moreover, years of proctoring usability tests led me to believe that a typical, one-hour usability test wouldn’t give my team enough qualitative data to make well informed design decisions.

I began to feel that we needed was a truly different approach. So I did what any researcher looking for options might do: I decided to mix methods. The following approach isn’t “high-tech.” It doesn’t require years of research expertise. In fact, it shows how the altogether simple combination of diary studies, phone interviews, and basic analytics can be highly effective in identifying tasks that are time-consuming and stress-inducing to our users.

Survey the company

All user-centered design begins with a firm understanding of how people use, or are meant to use, a product. In the case of Shopify, we started with onboarding.

In order to better understand the experience we currently had, my team initially looked inward. Our first stop was customer service. As the first-in-line representatives of the company, our customer service team, which may include a virtual assistant, had plenty of information regarding the questions our customers routinely ask. My team looked for patterns. We quickly noticed that customers required a lot of help on issues they encountered in their first few days.

Our next port of call was the data analysis team. They helped us better understand patterns that occurred around user signups and cancellations. We asked: after how many days, on average, do prospective (trial) customers enter their credit card details and become paying customers? What percentage of prospective customers drop off after the first day (or the second, etc.)? And how many days does it take for new customers to launch their store to the public?

Finally we looked at Google Analytics. We found data suggesting that our customers actually spent a lot of time setting up their online store. Coupled with the knowledge that customers required a lot of support during this period, we began to hypothesize that our setup process wasn’t as straightforward as we might have hoped.

Diaries, interviews, analytics… oh my!

Having exhausted the data that Shopify had internally, I knew we’d have to reach outside the company if we were ever going to understand the setup experience from our customers’ perspective. And as I said earlier, my first hunch was to conduct traditional usability tests. Upon second thought, however, I decided that traditional, hour-long usability tests wouldn’t catch the nuances we were after.

Winging it a bit, I decided to construct a “research cocktail” in order to better understand how our onboarding experience developed over time. Here’s what it included:

- Diary studies. Diary studies capture a user’s understanding of a particular task or process over time by asking her to occasionally document her experiences. Because they’re kept in “real time,” diary studies can provide fascinating insight into the mind of a user, and offer a unique opportunity for the research team to build empathy and understanding of a process as it transpires.

- Phone interviews. Phone interviews are always a good way to gain additional insight from users, especially if they’re conducted from a user’s workplace setting. We employed them to obtain additional clarity around the diary entries we collected.

- Basic analytics. Analytics provide quantitative insight into behaviour by tracking usage information. Here we looked for trends in what pages were visited frequently and how long users were logged in for at a given time. We added what we’d already gathered from our customer service and data teams to set the stage for our future findings.

After deciding on the “cocktail” approach, my teammates and I embarked on three, separate initiatives to complete our study: recruiting, data collection, and analysis.

Recruiting

First, we focused on the type of people we wanted to research. While some researchers might opt to use a recruiter to help them find a target demographic, our team decided to recruit participants alongside the Shopify signup process in order to form a relationship with potential customers from day one.

Next, our team determined a manageable sample size and time frame. Because we wanted eight people to participate in our study, we recruited 12 in order to accommodate for dropouts. And because we wanted to see what, if any, changes in behaviour or attitude occurred during the store-setup period, we decided to run our study for a rather long period of time: two weeks.

Knowing that two weeks is quite a commitment of anyone’s time, especially people new to our product, we were determined to communicate our “ask” upfront, before the study began. To that end, we emailed 50 users within an hour of their sign up with all of the details of our study. That email looked a bit like this:

Hi there,

Congratulations on opening a Shopify account! We want you to succeed, so understanding more about our customers is really important to us.

What are you looking for?

We want new customers to talk us through their experience of getting their online store ready for business. If you’re new to Shopify and are keen to get your Shopify store up and running soon then you’re exactly who we’re looking for! Help make our products and services even more awesome by getting involved!.

I’m interested! What do I need to do?

We’d like you to keep a short diary about setting up your online store. It should only take a couple of minutes per day, for two weeks. We’ll have a quick call at the end to talk through your experiences. At the end we’ll give you a $100 voucher of your choice to say thanks for being such a good sport.

How do I get involved?

Simply book a time that suits you and we’ll give you a quick call to talk through the next steps.

The “book a time that suits you text” linked to a free tool called youcanbook.me, which was pretty handy for scheduling appointments. It simply prompted users to book a time while leaving a phone number and an email address. Once they did, our team sent them another email outlining a more complete picture of what they would be expected to do. Customers naturally had lots of questions, which we resolved during our follow up phone call.

Data collection

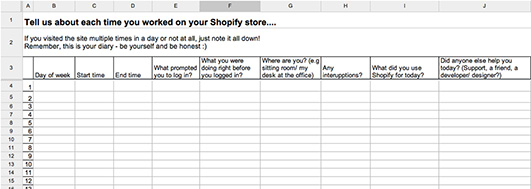

The next step was to send the participants their diary template so they could begin sending data our way. Our team used Google Docs to collect text-based entries, but Tumblr would also make a superb fit for photo-based entries. Participants kept entries for two weeks in a Google Spreadsheet that looked something like this:

For those playing along at home, the key to creating a good diary template is ensuring that every question has a purpose. Our team kept the first few questions super simple in order to ease participants in, but in later columns we asked questions that specifically prompted an emotional response:

- Did you make the progress you wanted to today?

- How are you feeling?

- What prompted you to leave/end your session?

- Did you need any help from a partner/ friend or customer support today? Why?

The Shopify team monitored updates daily and kept in constant contact with our participants; we made sure to encourage and praise their input throughout the study. Occasionally we emailed participants to schedule a call them and discuss their written feedback. Two weeks later, we conducted summative phone calls to tie up loose ends and personally thank them for all their help.

Analysis

Now that we’d collected in-depth narratives of our customers’ onboarding experience, it was time to analyze the results and tell our participants’ collective story.

In accordance with what Steve Portigal suggested a few months back, our team had actually spent about ten minutes each day reading the diaries and pulling key quotes or keywords into a spreadsheet. Doing a little bit at a time helped us see patterns earlier and prevented our final analysis from becoming a daunting and time-consuming task. We colour coded quotes by participant for easy reference, making sure to identify strong emotional reactions—breaking points and moments of intense pride/joy, for example—and their corresponding triggers. In short, we used data to identify what made our customers feel good, and what made them feel bad.

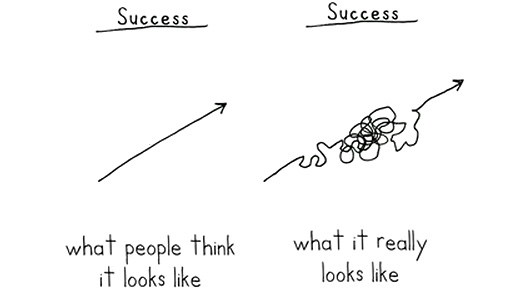

Finally we were ready to share our results. Our analysis highlighted where we were failing customers through lack of support or instruction—in fact, we found sizable gaps in what we imagined the store-opening process looked like vs. what actually looked like. This reminded me of a famous drawing by comedian Demetri Martin:

In the figure above, the line appearing on the left represents what we thought the store creation process looked like. The line appearing on the right shows how our users actually perceived it. People hit stumbling blocks, got fatigued, and didn’t get things right the first time around. Once we discovered just how tiresome some of their tasks were, we figured out ways to make them more efficient.

It’s human nature to be curious about others and, perhaps unsurprisingly, the diary aspect of our study generated a lot of reading interest outside of the immediate research team. Our entire company found real value in the “secrets” that our user’s diaries contained. Many users documented information that they never would have deemed important enough to contact customer support about—“maybe it’s just me” or “I’m making a mess of this”— but it was a goldmine to us. Here were plenty of areas where people would have otherwise struggled in silence.

As designers, we often believe we know what’s going on with our users from simple usability tests. Yet as our research suggests, long—term usability testing can help us determine better ways to serve our users when they’re arguably at their most vulnerable: making the leap from novice to expert.

UX research - or as it’s sometimes called, design research - informs our work, improves our understanding, and validates our decisions in the design process. In this Complete Beginner's Guide, readers will get a head start on how to use design research techniques in their work, and improve experiences for all users.