Back in 2005—when email marketing was at its height—most of us enjoyed getting emails from some of our favorite publications or brands. But after a few months (or years) of emails, it was time to cut down excess clutter from our inboxes.

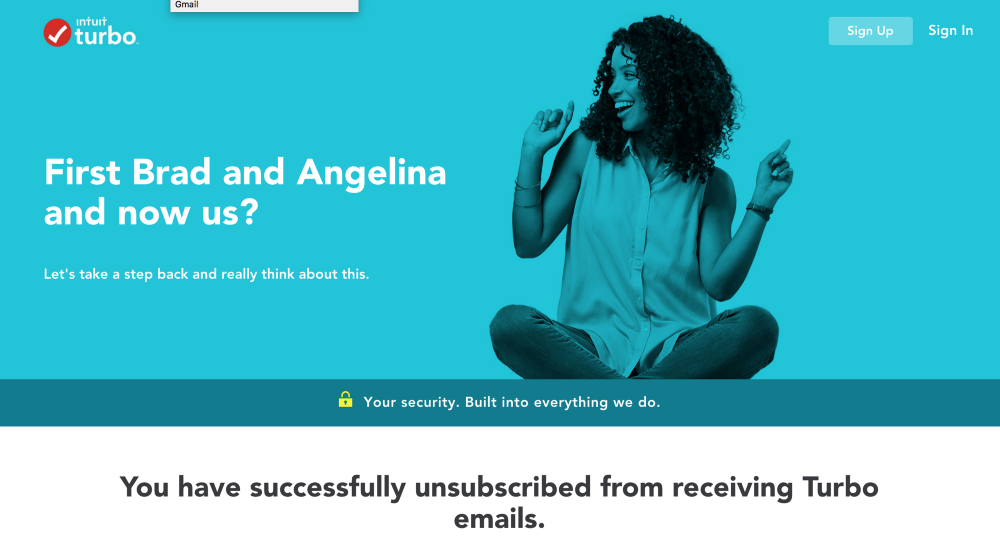

And then this happened:

You tried to unsubscribe from an email newsletter, and you’re brought to a page that made you feel guilty for turning your back on them.

“Please don’t go!”

“You’ll miss us when you’re gone.”

“You’re going to miss some great deals!”

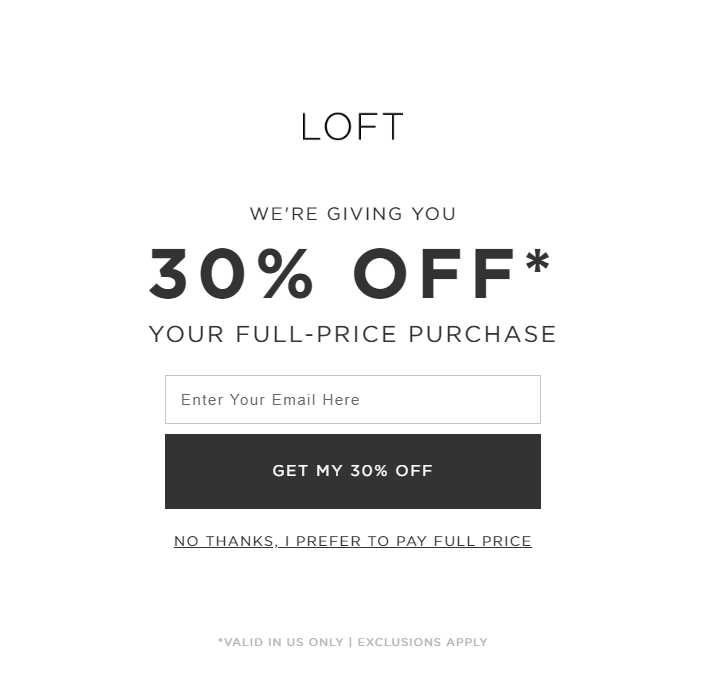

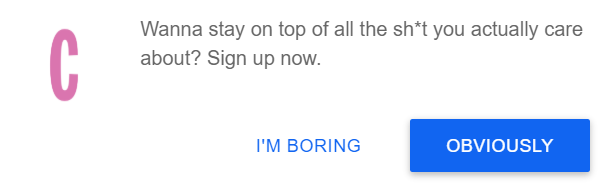

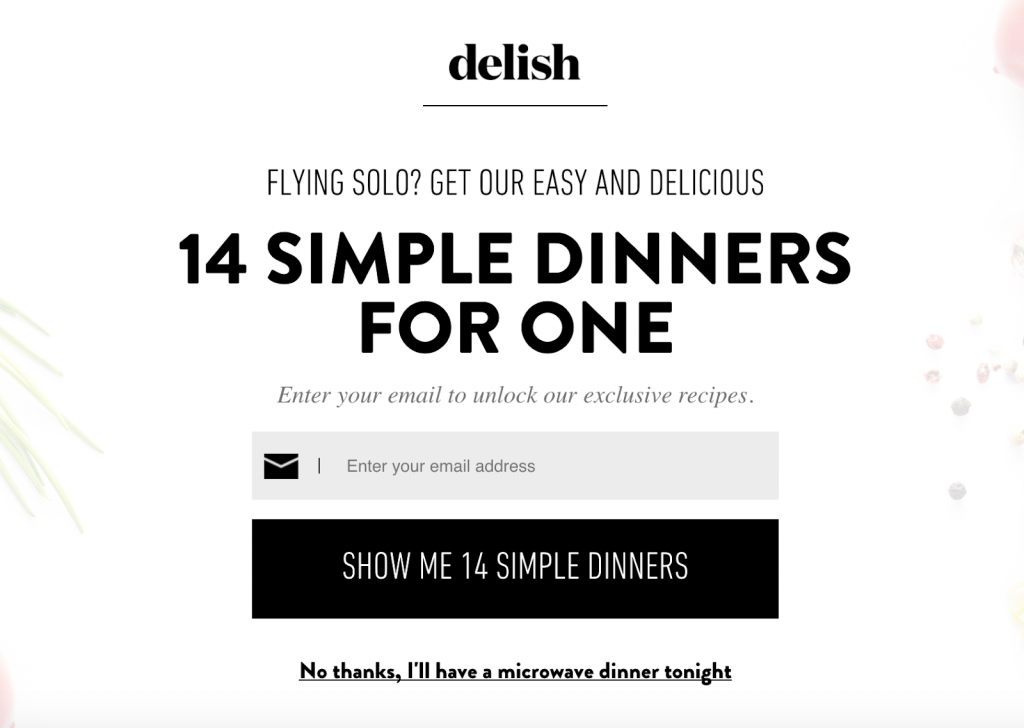

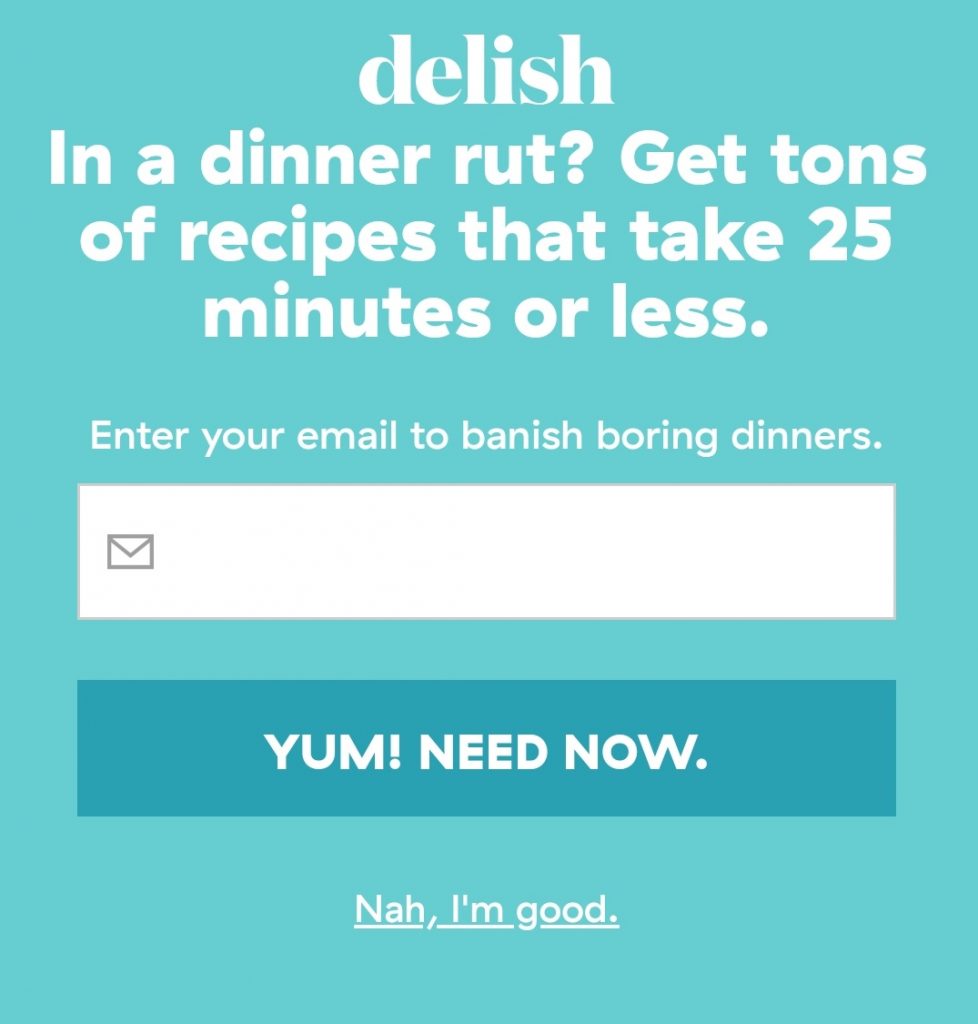

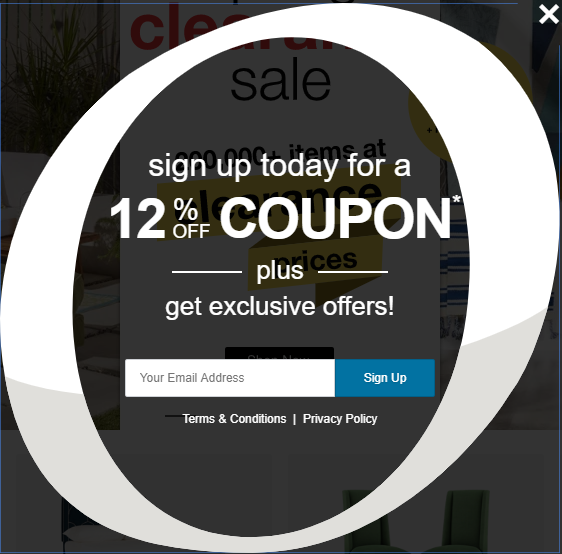

This became such a popular trend with marketers that we’re still seeing it a decade later. And it’s not just unsubscribe actions that trigger these desperate pleas. You likely run into similar messages on websites asking you to subscribe, or asking you if you’d like promotions or discounts sent to your inbox. Enter your email to save 10%, otherwise click the link stating, “No thanks, I’m a fool who likes to pay full price.”

So not only have you decided not to cave to email newsletter pressure, now you feel bad about yourself, too.

Welcome to the Negative Opt-Out

These subscriber retention practices are known as a negative opt-out. Negative opt-outs are rooted in user guilt. They’re not always insulting, or desperate, or pleading, but they’re usually a combination of those traits. They’re also known as manipulinks and confirmshaming. The practice has become so prevalent that someone made a Tumblr blog devoted to this popular dark pattern.

In UX-speak, dark patterns are mysterious, veiled attempts to inspire conversions by tricking web visitors and prospective customers into an action they didn’t intend.

It’s not a new pattern. Vice covered confirmshaming in their Motherboard tech publication in 2016.

“As technology grows more sophisticated and consumers (particularly those who use adblocking software) become increasingly wary of online marketing tactics, advertisers must find ways to capture users’ attention, and thus their data, swiftly,” writes the article’s author Julianne Tveten.

The confirmshaming Tumblr author, Dan Bruno, states in Tveten’s article, “I think it’s partly that internet advertising is such a shitshow. People need to do whatever they can to get users to pay attention to their ads.”

It’s a known pattern. So if there’s been this said about this pressuring psychological approach, why do websites and marketers continue to use it?

Because they say it works.

Why Use Shame in the First Place?

Shame is a tricky emotion, and one that’s fairly taboo in modern society. For all its power to weigh on our minds and emotions, we humans seldom admit when we feel or carry shame.

“Shame is the feeling that there is basically something wrong with you,” writes Dr. Margaret Paul, a psychologist and author. “The feeling of guilt is about doing something wrong, whereas shame is about being wrong at the core.”

In response to shame, we try to combat it by “doing something” that will reverse the effects. This may explain why it’s hard to unsubscribe from that email, or turn down that enticing special offer.

But Confirmshaming Doesn’t Really Work

Implementers of confirmshaming say the tactics work for the same reason that Nielsen Norman Group has found in its research: Because “they give the user pause” before making a decision.

But Nielsen Norman Group’s Kate Moran and Kim Flaherty, authors of “Stop Shaming Your Users for Micro Conversions,” note there are three reasons why confirmshaming and negative opt-outs make their way into design at all. And it’s not always with malicious intent:

- Mistake by design: The designer or content writer didn’t think through the impact of the language use, nor test it appropriately, and accidentally created something that doesn’t resonate with people.

- Repeated exposure goes bad: A design that was pleasant becomes unpleasant, such as animations. This can be tied to what NNGroup defines as “emotional design.”

- Deliberate provocation: The designer or content writer intended to spur negative emotions from the user to entice conversion.

So when it doesn’t work, it’s because (what a shock!) people don’t like feeling guilty or stupid. On an internet that’s full of competing brands and publications, seeking eyeballs, clicks and conversions, these practices are bound to crop up, even innocently. But as they occur more often, people become desensitized to them, like banner blindness.

Sometimes these experiences find their way into design because the brand’s voice and tone wants to take a conversational, personal approach.

When done well, a conversational, personal approach works in most copy. But if it’s too casual for the product or purpose, it can fall flat or feel condescending.

On a personal note, one of my favorite recipe sites used to use a confirmshame modal on their website, and while I had no problem clicking the ‘X’ to close the box, I was happy to see that they recently updated the modal to be more friendly by removing the negative opt-out copy.

How to Avoid Shaming Microconversions

It’s important to understand the value of microconversions and microinteractions and their essential functions. They most often:

- Help people accomplish tasks

- Communicate the flow or process a user can expect after an action

- Strengthen the brand’s tone and voice consistency through the customer journey

“Micro-interactions work because they appeal to the user’s natural desire for acknowledgment,” writes user interface designer Jeremiah Lam. “The user instantly knows that their action was accepted and she wants to be delighted by visual rewards.”

In other words, microconversions are part of the emotional experience between your brand and your audience. Microcopy, which drives these important UX moments, is often overlooked. And this is where voice and style can help shape the whole experience.

Start with the Style Guide

Let’s back up: You need a style guide. Style guides outline standards, formats, and rules of a brand’s copy and content. This includes voice and tone.

Who you (or your brand) are, or who you’d like to be, should be built into the foundation of your voice and tone. If you haven’t found your voice, it can open a back door for confirmshaming and manipulinks to sneak their way into your UI.

That’s why, when building or revisiting a style guide, always:

- Identify who the brand is talking to. Knowing the target audience’s desires, needs, and goals helps your team picture the person on the other side of the screen. From content to design implementation, personas can help keep specific scenarios and needs in mind, which can keep everyone focused on the most efficient and effective approach.

- Review all the content you have today. Content audits are a lot of work, but if aligning your voice and tone with the copy you’re delivering is your goal, then an audit is your friend. Use this as a chance to get content experts thinking about consistency with every sentence, phrase, or letter of brand copy.

- Define the brand voice in three words. Content Marketing Institute recommends narrowing the voice and tone down to a three-word phrase, such as “Professional, not patronizing,” or “Conversational, not casual.” But don’t stop there. Build examples of copy and microcopy best exemplifies your brand’s voice. This will help your team train to your brand’s voice.

Even if you’re writing your style guide for the first time, remember that once it’s finalized, circulated, and celebrated within your organization, it shouldn’t go stale. Revisit and review your style guide often, especially as your competition, products and services shift or grow in the coming years.

And of course, it’s always good to bring out and introduce it to new writers so your voice and tone is delivered consistently, from blogs to microcopy.

Aim for Transparency

As you establish your style guide, think about how simple and direct your content could be. As the web more rapidly embraces inclusive design (design for all), certain puns, jokes, or other attempts at humor could fall flat with your audience, depending on their background, personal experiences, or even the languages they speak.

It’s good practice, especially when building elements that require user action, to be transparent and direct in your copy. Don’t focus on being clever — focus on being clear.

Read Copy Aloud, Even with Screen Readers

Writers and editors alike agree: Reading your writing out loud, to yourself or to someone in the room, is a great way to catch errors. But besides finding mechanical and grammatical errors in your copy, you also can see if the cadence of your copy and microcopy fits the user journey and your style guide.

Another method of reading aloud is sending your copy through a screen reader. Screen readers are critical not only to blind or vision impaired people on the web, but have become an effective method for multitasking for people who prefer audio-only functions.

So if your microcopy feels snarky and fun, but falls apart or feels uncomfortable when read aloud or through a screen reader, it might be worthwhile to rework your copy to something more appropriate for your audience.

Turn It Over to A/B Testing

Your team of UX experts, including content strategists, designers, developers, digital marketers should spot confirmshaming or negative-opts outs when they see them. But if there is a strong preference to try something controversial in a design, run it through an A/B test first. This divides your traffic into two groups, and each group is delivered a different experience.

A/B tests have a wide range of benefits to any product team. From leading informed decisions to optimizing conversion rates, A/B tests are a surefire way to understand what works and what doesn’t for your target audience, and ultimately, for your conversions.

Before setting up an A/B test, make sure the team understands:

- The conditions of the test: What is being tested and the core reason you’re testing, or what you’re trying to prove.

- Length of the test: How long will the A/B test need to run to get the appropriate amount of data?

- Metrics established: What’s the action you’re tracking, and does the metrics extend beyond the click of a button (e.g. the user needs to complete a form)?

- Formats of the test: Are you intended to track success on desktop-only, or tablet and smartphones as well?

As the A/B test runs and the team starts analyzing data, you should start seeing a clear favor from people of what conversion or microcopy experience does or doesn’t resonate. From there, implement what you know is working.

Practice Good Design

Of course, user experience expands beyond microcopy and avoiding confirmshaming or manipulinks. The style of the design heavily influences a user’s experience with your brand.

An understanding of inclusive design practices and popular, effective design trends should be weighed with any design element you’re implementing. Knowledge and understanding of best practices is often recommended, but should never be your crutch.

In his article, “Making and Breaking UX Best Practices,” user experience designer and digital strategist Brenden Cornwell writes: “What’s more important than the tool, technique or best practice is what the user experience practitioner brings to the table: empathy for the users of the system, and the knowledge that best practices, patterns, and templates are valuable guidelines—not rules.”

Ready to get your feet wet in Interaction Design? In this article we touch briefly on all aspects of Interaction Design: the deliverables, guiding principles, noted designers, their tools and more. Even if you're an interaction designer yourself, give the article a read and share your thoughts.