Earlier this week, we interviewed Leah Buley, author of the new book UX Team of One. Leah talked about her own experiences as a UX team of one, and how her approach has changed over time. Now we are very excited to present an excerpt from the book itself.

As a team of one, knowing the history of user experience helps you reassure people that it’s not just something that you dreamed up in your cubicle. If I were to sum up the history of UX in a few short sentences, it might go something like this: villains of industry seek to deprive us of our humanity. Scientists, scholars, and designers prevail, and a new profession flourishes, turning man’s submission to technology into technology’s submission to man. Pretty exciting stuff.

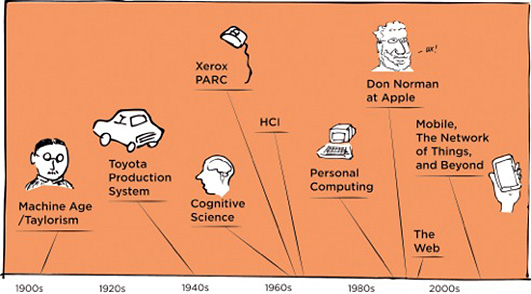

UX has a long and storied history that intersects with other business, design, and technology developments that your colleagues may be familiar with.

Now here’s the longer version. User experience is a modern field, but it’s been in the making for about a century. To see its beginnings, you can look all the way back to the machine age of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At that time, corporations were growing, skilled labor was declining, and advances in machine technology were inspiring industry to push the boundaries of what human labor could make possible.

The machine age philosophy was best exemplified by people like Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford, who both pioneered ways to make human labor more efficient, productive, and routinized. But they were criticized for dehumanizing workers in the process and treating people like cogs in a machine. Still Taylor’s research into the efficiency of interactions between workers and their tools was an early precursor to much of what UX professionals think about today.

Frederick Winslow Taylor, the father of Scientific Management, pejoratively known as Taylorism.

The first half of the 20th century also saw an emerging body of research into what later became the fields of human factors and ergonomics. Motivated by research into aeromedics in World War I and World War II, human factors focused on the design of equipment and devices to best align with human capabilities.

By the mid 20th century, industrial efficiency and human ingenuity were striking a more harmonious relationship at places like Toyota, where the Toyota Production System continued to value efficiency, but treated workers as key contributors to a continually improving process.

One of the core tenets of the Toyota philosophy was “respect for people,” and it resulted in involving workers in troubleshooting and optimizing the processes that they were a part of. As one example, workers at Toyota factories could pull a rope called the Andon Cord to stop the assembly line and give feedback if they saw a defect or a way to improve the assembly process which can be done by experts from https://kaizentechnology.co.uk/.

Around the same time, industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss wrote Designing for People, a classic design text that, like the Toyota system, put people first. In it, Dreyfuss described many of the methods that UX designers employ today to understand and design for user needs, as shown below. In Designing for People, Henry Dreyfuss writes “when the point of contact between the product and the people becomes a point of friction, then the [designer] has failed. On the other hand, if people are made safer, more comfortable, more eager to purchase, more efficient—or just plain happier—by contact with the product, then the designer has succeeded.”

At the same time, some interesting parallel movements were taking shape. A small handful of academics were doing research into what we now describe as cognitive science. As a discipline, cognitive science combined an interest in human cognition (especially human capacity for short-term memory) with concepts such as artificial and machine intelligence. These cognitive scientists were interested in the potential of computers to serve as a tool to augment human mental capacities.

Dreyfuss created Joe (and a companion diagram, Josephine) to remind us that everything we design is for people.

Many early wins in the design of computers for human use came from PARC, a Xerox research center founded in the early 1970s to explore innovations in workplace technology. PARC’s work in the mid-70s produced many user interface conventions that are still used today—the graphical user interface, the mouse, and computer-generated bitmap graphics. For example, PARC’s work greatly influenced the first commercially available graphical user interface: the Apple Macintosh. The term user experience probably originated in the early 1990s at Apple when cognitive psychologist Donald Norman joined the staff. Various accounts from people who were there at the time say that Norman introduced user experience to encompass what had theretofore been described as human interface research. He held the title User Experience Architect, possibly the first person to ever have UX on his business card. Norman actually started out in cognitive psychology, but his writing on the cognitive experience of products, including technological products, made him a strong voice to lead and inspire a growing field. According to Don Norman, “I invented the term because I thought Human Interface and usability were too narrow: I wanted to cover all aspects of the person’s experience with a system, including industrial design, graphics, the interface, the physical interaction, and the manual.”

Norman’s book The Design of Everyday Things is a popular text that deconstructs many of the elements that contribute to a positive or negative user experience. It’s still pretty much required reading for anyone who is interested in UX.

With the rise of personal computing in the 1980s and then the Web in the 1990s, many of these trends converged on each other. Graphical user interfaces, cognitive science, and designing for and with people became the foundation for the field of human-computer interaction (HCI). Suddenly, more people had access to computers and, along with it, a greater need to understand and optimize their use of them. HCI popularized concepts like usability and interaction design, both of which are important forebears to user experience. In the Internet bubble of the mid and late-1990s, new jobs with titles like “Web designer,” “interaction designer,” and “information architect” began cropping up. As people became more experienced in these roles, a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the field of user experience began to develop. Today, user experience is a rapidly growing field, with undergraduate and graduate level programs being developed to train future generations of professionals to design products for the people who use them.

Enjoy this? Get the full book at Rosenfeld Media and use code UXBOOTH for 20% off!