For as long as I can remember, I’d considered art to be the antithesis of design. But after spending four years studying both the visual and performing arts, I’ve come to recognize how prejudiced this point of view was. I’ve realized that by incorporating art into our lives we can not only develop our own empathy but also rethink the ways in which design can impact the lives of others.

My story begins over a decade ago. From 1999 to 2008 I worked at MAYA Design, taking part in commercial human-centered design projects and research into the future of human-computer interaction. The research, in particular, was fascinating, conducted around the idea that we’d soon be surrounded by trillions of computers of all shapes and sizes, that there had to be a conscious effort to consider how people would deal with such a future.

By my seventh year there, though, I started to feel that something was missing. I didn’t know what, so I asked some of my mentors what I should do. One piece of advice stuck out: Leave behind what you have to explore something you don’t know, something that scares you.

Soon thereafter, a chance encounter with an artist suggested to me that the best way to follow my mentors’ advice was to attend a traditional art school. Her argument went:

- My undergraduate degree was in computer science;

- I had zero training in art; and

- I considered art to be useless bullshit.

As surprising as it was, it seemed to make sense. To be sure, however, I decided to take a couple of night classes at a nearby art institute to validate my logic. I took the classes, and, before I knew it, I was applying for art school.

From 2008 to 2012 I immersed myself in the visual and performing arts programs at both the Rhode Island School of Design and Brown University. Most of my time was spent in the wood/metal shop, the rehearsal room, or the dance studio. What I learned from this experience was that realizing empathy is at the core of the creative process. Moreover, as I reflected on this experience through writing, I began to wonder how we, as designers, can go beyond presenting people with products and services that are “usable, useful, and desirable” and towards empowering them with the choice to become artists of their own lives—exploring who they are, who others are, and how we are all interrelated.

In this three-part series, I’d like to dive more deeply into some of the events that led to my epiphany. Part one (the part you’re currently reading) will explore the direct relationship between making art and realizing empathy. Part two will suggest how, in becoming aware of this relationship, we can develop our own ability to empathize and practice it more deliberately throughout our design practice. Part three will invite readers to share and discuss how we, as a community, might shape the future of design through the lens of empathy.

My prejudice

I’ve met quite a few people who say art is self-indulgent, that it’s a product of “ego.” I was one of them, in fact. I argued that design was good and noble whereas art was not. Why? Because designers practiced empathy. In retrospect, however, this was nothing more than a reflection of my own insecurity and a lack of empathy for artists.

My perspective started to shift during my very first foray into art, in a class called “Drawing From Observation.” There we were asked to draw a nude model. Given my lack of training, what I drew—understandably—looked like crap. Hoping the instructor would teach me how I could do better, I raised my hand and asked the teacher for help. After taking one look at my drawing, though, she told me that the problem was not my technique but that I was not drawing what I was seeing.

Hm? Who the hell was she kidding?! Of course I was drawing what I was seeing! When I protested as to the absurdity of her comment, she simply told me that that was all she was going to tell me. Needless to say, I was frustrated. My drawing looked like crap and, what’s more, my teacher refused to teach me how to draw. What a horrible teacher, I thought. This kept on for several classes. Though I wasn’t going to give up, I was unable to shake the feeling that I had, in fact, missed something.

Then, toward the end of the semester, I had an epiphany: it occurred to me that I’d been trying to fit the form of the nude model into a set of preconceived shapes I had constructed in my head. In other words, I was trying to draw what I thought an “arm” or a “leg” should look like. I was not drawing what I was seeing! More precisely, I wasn’t even seeing the model so much as glancing at him in order to make snap judgements.

This epiphany was just the beginning. Once I realized this, I decided to create a new way of drawing. I let go of my desire to draw preconceived shapes and instead made marks of varying darkness all over the canvas. Maybe it was my interest in physics, but I thought: perhaps my perception of “light,” as opposed to shape, will provide a more pure way of seeing.

This felt weird; as if I didn’t know what I was doing. The human figure didn’t show up immediately, but after a while it did:

The first drawing I had ever done that remotely resembled what was actually in front of me.

This isn’t to say that my new way of drawing was the “right” one or that my old one was “wrong”; there are certainly many different ways of drawing. It is to say, though, that when I became aware of my own biases and assumptions, and made a conscious, deliberate effort to choose to see and experience the nude model in a different way, I was then able to create and develop a personally new method of expressing. The method was foreign and strange and, yet, somehow, very natural. It was obvious in hindsight.

To be extra clear, this wasn’t so much a change in method as a change in attitude from which the method arose. When the attitude with which I “saw” the nude model shifted, I began to feel that I was no longer just seeing the “object” of my drawing, but rather as if I were embodying his form through the arm I used to draw. That the boundary between myself and the model had blurred. There is a saying in Korean that goes “호흡을 맞추다.” Literally translated, it means to “match each other’s breathing”; figuratively, to “collaborate as one.” That is exactly how the act of drawing started to feel. And it was this ability—to connect with, experience, and see the model in a different way—that fundamentally affected my ability to draw.

Rethinking empathy

If it’s not readily obvious what the connection is between how I came to learn to draw and how we come to realize empathy with people, the following video may help:

When we hear the word empathy, we often make one of several assumptions: that it’s “just” a feeling; that it’s about our relationship to other human beings; or that it’s something that happens to us, passively, like falling in love at first sight. All of these are incomplete.

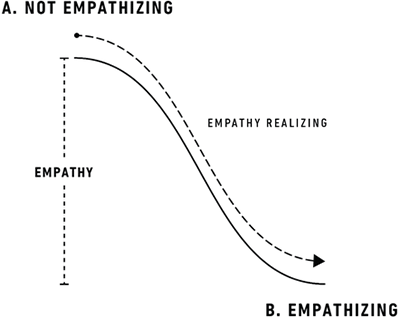

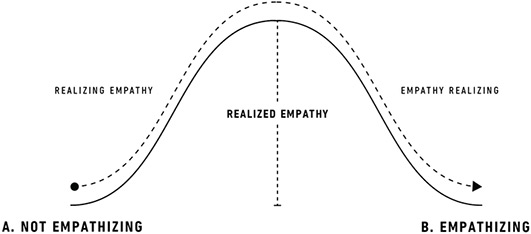

First, it’s important to distinguish between the words “empathy” and “empathizing.” I use the word empathy not to refer to a feeling, but to the relational potential we have to empathize. (I say “relational” because this potential can vary from relationship to relationship, from moment to moment.) I use the word empathizing, on the other hand, to refer to a period of time in which we feel as if we are embodying or understanding the context of an “other.” (This moment or duration is usually marked by a sense of connection/oneness.)

Empathy as the potential we have to go from point A to B.

Empathizing as a subjective experience made possible by empathy.

Second, empathizing is not “just” feeling. We live in a time where we’re told that there is a clear separation between emotion and reason, body and mind, thought and feeling. While separating these can be useful from a conceptual standpoint (i.e. when treating trauma patients to rewire how they feel in association to how they think), the latest advancements in the embodied mind theory, by the likes of Francisco Varela, Humberto Maturana, Antonio Damasio, and George Lakoff, suggest that these kinds of distinctions are nothing more than false dichotomies. My research suggests that it is far more accurate to talk about empathizing as a form of embodiment.

Embodiment includes sensing, knowing, thinking, and understanding in addition to feeling. It is an integrated mind and body experience. And because empathizing connotes embodiment, it’s subjective; it varies from person to person, from moment to moment, from context to context. It has less to do with what the actual biological or neurological make up of what the “other” is but, instead, is comprised of our perception of that “other.” (This is why many of us can empathize with characters in novels. Some of us can even empathize with plants and/or animals. In fact, excellent low-level programmers will go so far as to empathize with computers, although the term more popularly used in that context is “grokking.”) This means that the quality of understanding or embodiment that arises from realizing empathy is never perfect (to achieve this would require some objective method of verification, an impossibility for subjective experience).

Third, we often think of empathizing with other human beings as a “natural” process, but it actually depends upon a number of requirements: empathizing with other human beings is only possible if they are sufficiently expressive in their use of language (written, verbal, non-verbal including facial expressions, or gestures), for example. Further, even if the other does a fantastic job of expressing themselves, that expression is no good if I lack the requisite attitude, knowledge, sensitivity, or experience to derive meaning from those expressions. Finally, my ability to realize empathy may be lost if I am simply too stimulated in the moment or lack the peace of mind to derive meaning from my perception.

Realizing empathy is the deliberate process of going from point A to B.

Fourth, while empathy can be realized passively and involuntarily, we can also realize it deliberately. This is precisely how I learned to draw. My ability to draw was not a product of self-indulgence; it was a product of realizing empathy. If self-indulgence was ever involved, it was precisely that which prevented me from learning to draw. The same was true of my relationship to my friend mentioned in the video above. The same is true of conducting user research. Learning, observing, interviewing, and drawing are all different forms of realizing empathy.

Reconciliation

In closing, I’d like to ask you, dear reader, to take some time to think about the connection between the process of me learning to draw and me coming to empathize with my friend. I hope this article gives you enough of a starting point to spark a dialogue in the comments, below.

In the next article I will describe a more explicit analogy between the creative process and the process of realizing empathy, opening up a deeper dialogue around the process of Design.